It can seem like an unusual or confusing experience to have pain in your calf muscles when performing the Romanian deadlift (RDL, for short). After all, the RDL is a back and hamstring exercise, right? Well, there can be more to it than that, and this brief article will break down different reasons for experiencing pain in your calf and what it all means.

Calf pain from the Romanian deadlift (RDL) is often the result of sciatic nerve tension, fascial restriction in the posterior chain, and muscle tension in the hamstrings, popliteus and gastrocnemius muscles. Solutions involve sciatic nerve glides, fascial stretches and muscle release techniques.

Now, it should go without saying that the preceding paragraph is an immensely brief overview of the problem at hand. Keep on reading for some of the “secret sauce” details that can be game-changers when working to resolve this issue (assuming you want to know how to effectively tackle the underlying cause).

Related article: Hip Hinge Hamstring Pain: Causes & Solutions | Here’s What to do

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including for calf pain with RDLs. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

As I take you through this article, keep in mind that what I’ll be guiding you through is the more common causes of what might be going on, but it’s certainly not an all-inclusive list. As of special note: if your pain is only in one calf, has seemingly come out of nowhere, and you find your calf to be red, hot, and/or swollen, get immediate medical attention, as it could be a blood clot — highly unlikely if you’re young and otherwise healthy, but just keep that in mind as these things can happen.

A quick solution: Ankle plantarflexion

While it’s important to discuss specific causes of calf pain from RDLs, it’s a good idea to introduce a quick solution you can immediately implement for your training as you work to correct the underlying cause of your calf discomfort or pain.

Whether your calf pain is coming from abnormal muscle tension or nerve tension, having your heels slightly elevated on a surface while performing the RDL can often significantly reduce discomfort.

If your calf pain has been severe to the point that you can’t tolerate performing the RDL, this heel-elevated strategy might not be appropriate. However, if your calf pain has been more on the mild side, it might be a nice workaround until you fully resolve the issue.

What happens when the heels are elevated?

Having your heels elevated by approximately one or two inches shortens up the muscle length of the gastrocnemius (the calf muscle). As a result, you’ll find it much more tolerable to perform the RDL (or any other standing exercise that requires you to otherwise lengthen out your backside).

I wouldn’t advocate that you settle on this strategy to be your “forever solution,” however, it may just be the ticket to let you continue performing RDLs for the time being as you work on getting the underlying issue under control.

Some common items you can stand on might be:

- A 2×4 or 2×6 plank

- Weight plates

You can play around with the height, but keep it under two inches and make sure that whatever your heels are resting on is/are sturdy so that it won’t mess with your ability to execute perfect form when performing your RDLs.

Related article: Four Handy Exercises to Help Loosen Stiff Ankles in All Directions

Sciatic nerve tension

For all of the lifters and active individuals whom I treat, sciatic nerve tension is the sneakiest yet most common cause of sensations of calf tightness or pain for hip hinging movements, such as the RDL. The reason why it’s so sneaky is that it can easily be mistaken for hamstring tension.

Sciatic nerve tension may feel like you’re dealing with tight calves. Still, it’s a different beast entirely and one that requires an entirely different intervention to resolve.

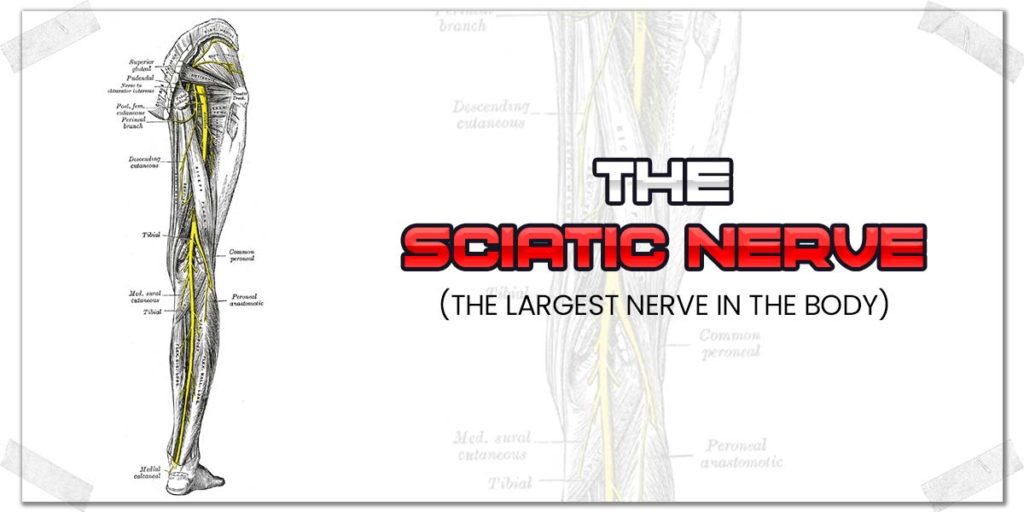

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body, and it essentially runs all the way down to your foot. If it’s irritated, you can absolutely feel sensations of tightness or discomfort in your calf. I see it all the time when working with lifters and individuals in the clinic.

FYI: The sciatic nerve becomes the tibial nerve as it crosses behind the knee and runs down the calf. For the sake of simplicity within this article, however, I’ll just refer to it as the sciatic nerve.

What causes sciatic nerve tension?

Anytime you have tension or irritation in your sciatic nerve, you want to get to the root cause; if you don’t, you’ll likely keep running into this issue repeatedly. The sciatic nerve often becomes irritated (which causes the nerve to become tense or restricted) due to an underlying pathology (issue) within the lower back.

The sciatic nerve is comprised of various spinal nerves that exit from the spinal cord and merge together before running down the back of the leg. Issues involving the lumbar discs (such as bulges and herniations, among others) can put pressure on any of these spinal nerves (at the nerve root), which can cause tension and irritation throughout the entire nerve.

Pro tip: Disc bulges within the lumbar spine are often asymptomatic, meaning the disc may be compromised without the individual even knowing it.1,2

Other issues such as foraminal stenosis (a narrowing of the canal where the nerve root exits the spinal cord) can also lead to nerve root irritation.

How to tell: hamstrings or sciatic nerve?

Your best bet for differentiating between whether you’re dealing with an irritated sciatic nerve or just some tight calf muscles is to get a proper evaluation by an orthopedic specialist. We’re pretty good at differentiating these sorts of issues.

If a professional evaluation is not in the cards for you, however, you might be able to get a sense of which one it is by trying to perform a straight-leg raise test or slump test on yourself. These are neurodynamic tests that practitioners (such as myself) frequently use. It’s meant to be performed by a practitioner, but you might just be able to do a sort-of modified version on yourself.

Here’s a solid rundown by the PhysioTutors showing how the slump test helps determine if pain in the back of the leg is coming from the muscles or from the sciatic nerve:

Related article: One Hamstring Tighter Than the Other? Here’s Your Solution

Performing nerve glides

If it’s determined that your calf tension is coming from adverse neural tension, you’ll likely want to learn all about performing nerve gliding techniques to help restore the nerve’s mobility.

Check out this video by the PhysioTutors for a great explanation and rundown on how to perform nerve glides for your sciatic nerve:

Get in the habit of performing nerve glides a few times per day, every day if they’re tolerated well (i.e., not painful during the exercise or later on in the day). I often have my patients perform these glides upwards of five times per day, depending on their individual condition and circumstance. I’d suggest aiming for around fifteen to twenty repetitions as a general starting point.

Remember: Nerve glides should never be painful; it’s permissible for them to very transiently reproduce your sensation of tightness or discomfort when in a lengthened position, but only to a very mild extent.

Fascia & the posterior chain

The posterior chain refers to the muscles alongside the back of the body that all work synergistically to perform various movements – such as the RDL. While these muscles all have their own independent identity, dysfunction or restriction in one can produce discomfort or movement restriction in others.

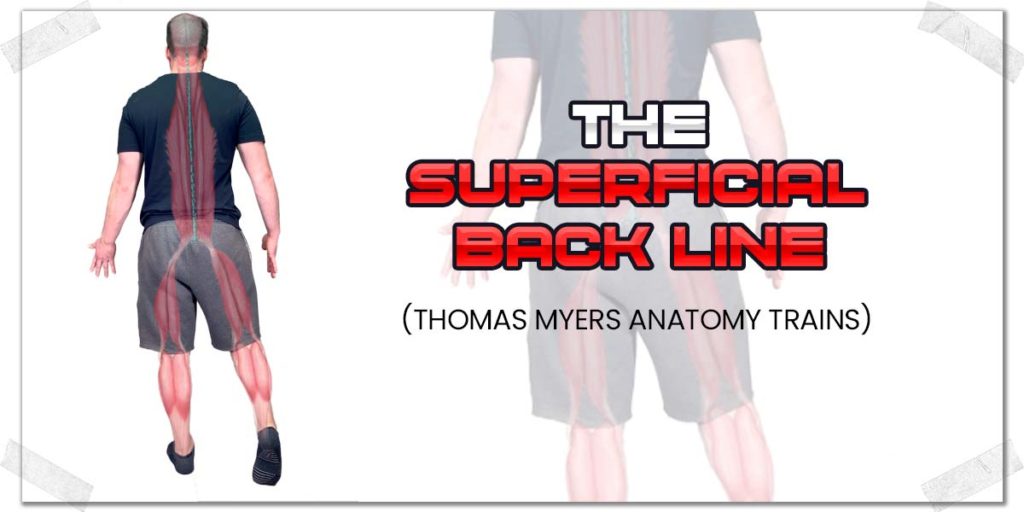

This is most notable with a type of movement restriction known as myofascial restriction (myo = muscle, fascial = fascia). Fascia is a fibrous type of connective tissue that surrounds the muscles. What’s really interesting about this connective tissue is that it exists in unique patterns that link it from one muscle to another. These fascial connections are often called myofascial trains or meridians, popularized by Thomas Meyers.

With the Romanian deadlift, the fascial train that’s most notable is the superficial back line. It consists of a unique connection between the calf muscles, the hamstrings, and some of the lower back muscles.

Imagine this fascial train as a highway with lots of traffic throughout. If traffic gets heavy, it can cause traffic to slow down or cause backups all the way down the road. Fascial restrictions within one area of a meridian can cause restricted movement anywhere along that particular pathway.

In other words: Fascial restrictions in one muscle can impede the movement abilities and performance in another along the same meridian.

Dealing with fascial restrictions

The easiest and simplest way to go about working on fascial restrictions likely taking place along your superficial back line is to perform a combination of dynamic stretches and self-soft tissue massage techniques to the muscles of this particular chain (though, of course, you could always opt for professional treatment as well). Myofascial release techniques along the superficial backline have been shown in a systematic review to be effective for improving flexibility.3

Here’s my suggestion for starting out with some self-treatment techniques targeting the fascial tissue along this particular line in an otherwise healthy individual:

- Rolling the bottom of the foot (or feet) with a tennis ball or lacrosse ball for approximately one minute.

- Using a travel roller or foam roller to roll the calf muscles for approximately one minute using moderate pressure and slow rolling.

- Voodoo/compression flossing of the hamstring bellies (mid-thigh level) for approximately one minute per leg.

- Foam rolling the mid & upper back for a few minutes.

Perform each of these techniques either in a series or separately throughout the day. Get in the habit of doing this daily, and within a couple of weeks, you’ll likely see or feel an improvement in your ability to perform an RDL while experiencing less calf pain in the process.

Referred pain: The hamstrings

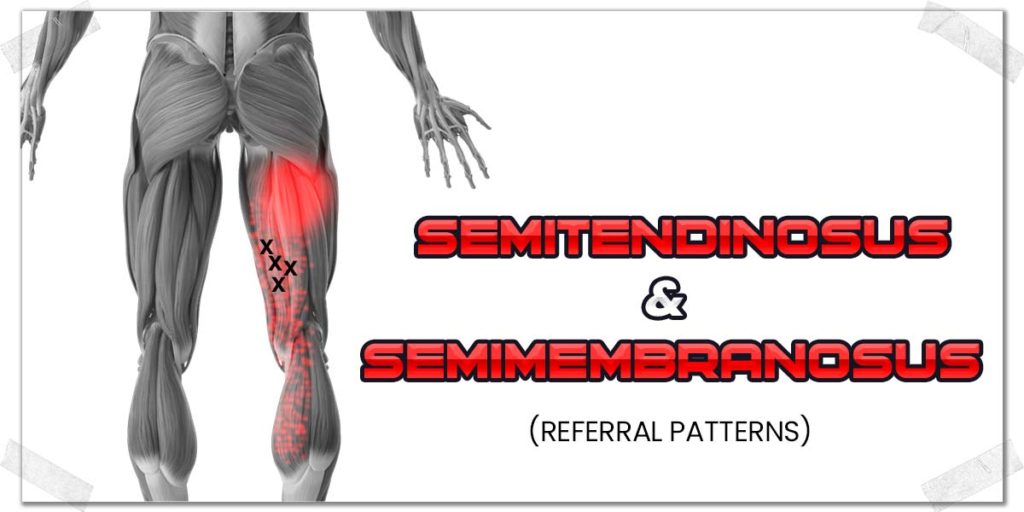

While a fascial restriction from the hamstrings could lead to sensations of tightness or discomfort in the calf muscles when performing the RDL, another unique culprit arising from the hamstrings that victimize the calves is the presence of trigger points within any of the three hamstring muscles.

A trigger point (often termed a muscle knot) refers to an area of heightened tension within a muscle. We don’t fully understand why these knots occur, but they’re essentially areas of heightened electrical activity within the muscle (which causes the portion of the muscle to “cease up.”)

The interesting thing about trigger points is their ability to send the sensation of pain or discomfort to a different area of the body other than where the underlying issue is occurring. This is the phenomenon of referred pain, and it’s extensively studied within the world of human anatomy and physiology.

In a sense, this can be very similar to the previous section involving myofascial restrictions along a fascial meridian. However, it’s still different enough to warrant its own section with the article.

All of the major skeletal muscles within the human body have well-established referral patterns in terms of where they will send their sensations of discomfort. With the hamstrings, they have the potential to refer sensations of discomfort or pain anywhere along the hamstrings themselves but also into the calf muscles as well.

In short: Referred pain from the hamstrings can feel like there’s something wrong with your calves when in fact, it’s simply the hamstrings themselves.

Dealing with referred pain from the hamstrings

It can be incredibly difficult for the average individual to tell whether or not their calf pain might be coming from the hamstrings themselves. However, one or two clues that could potentially help to point you in the right direction for determining if it is could include:

- The pain feels more diffuse and achy rather than feeling sharp or burning.

- The pain is felt when performing other movements or exercises that challenge or stretch the hamstrings but not the calves themselves.

If you suspect that your calf pain is referred from your hamstrings, getting treatment for the hamstring muscles could help. It could be in the form of soft tissue massage or through self-treatment techniques such as:

- Compression flossing

- Dynamic stretches

- Heating modalities

Obviously, professional treatment will likely yield the quickest and most significant results. However, if you treat things yourself, you can still make some favorable changes with deliberate effort and consistency. Pick the soft tissue treatment methods that work best for you and you can make some good things happen!

The popliteus

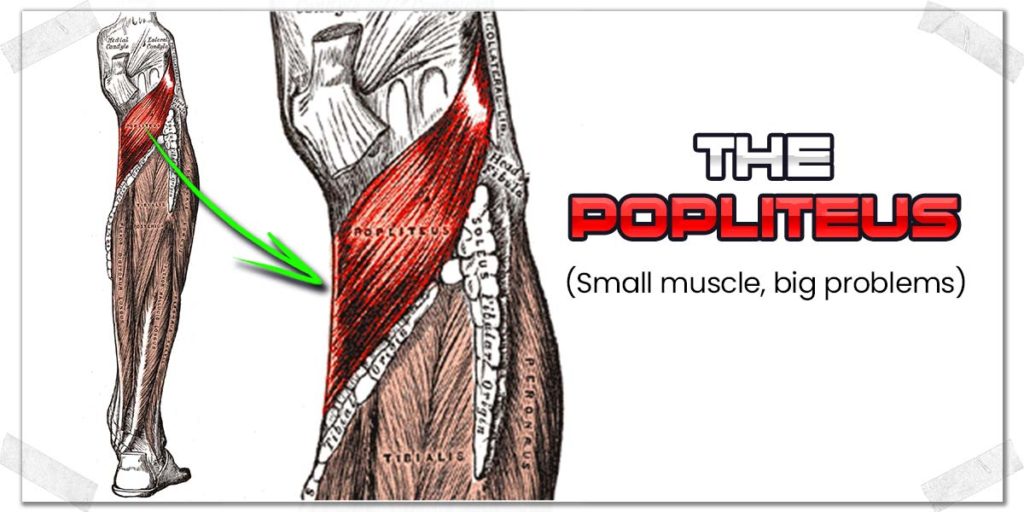

If there were ever an award given out to the least well-known muscle that can wreak the most havoc, it would very likely be the popliteus.

This little muscle lives behind the knee and can often become tight or irritable, producing sensations of tightness or discomfort. And since this muscle lives underneath the calf muscle, it can feel as if the calf is the problem (especially since the average person isn’t aware of the existence of Mr. popliteus).

Since the popliteus crosses the back of the knee joint, the more you extend (straighten) your knee (such as with the RDL), the more stretched out this tight muscle becomes. Tight muscles are sensitive to being stretched, meaning as the muscle is lengthened, you’ll feel the discomfort or pain when you otherwise shouldn’t.

Taking care of the popliteus

This can be a tricky issue to treat; the popliteus is a deep muscle, with its muscle belly sitting beneath both the gastrocnemius muscle and soleus muscle. To make it even trickier to treat, the tibial nerve, artery and vein run directly over top of it, so you don’t want to be pressing all willy-nilly directly behind the knee joint where those structures are located.

An orthopedic specialist will be able to treat the popliteus for you. Still, if getting treatment from a qualified specialist isn’t in the cards for you, you might be able to access one or two areas of the muscle and provide sustained pressure with your thumbs or a firm ball (such as a lacrosse ball or tennis ball).

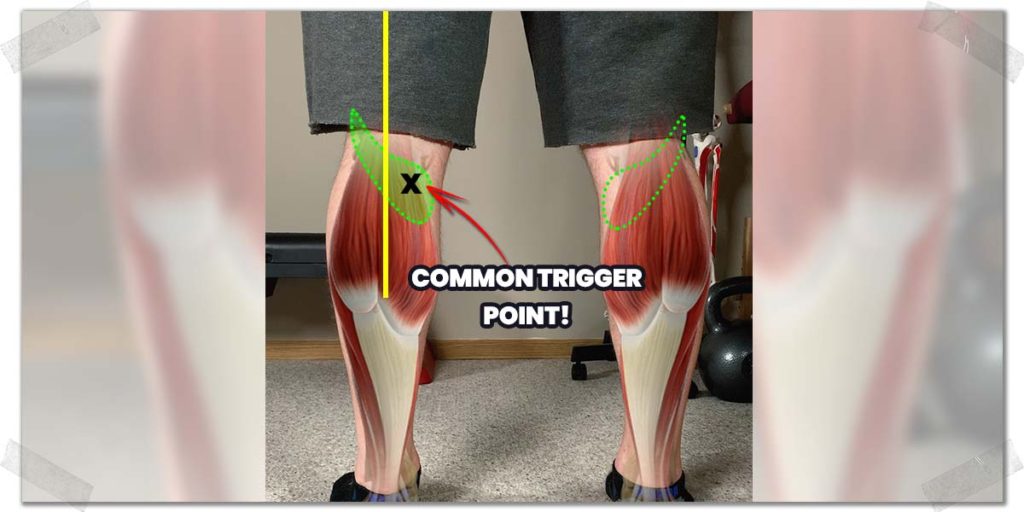

The popliteus tends to produce aching, diffuse pain when its trigger points are palpated (pressed on). If you put some firm pressure (since the muscle is quite deep) over any of the spots in the picture below where the “X” is located, you may very well be on the trigger point. If so, just hold some sustained pressure here for a minute or so until the trigger point starts to “melt.”

Tight calves

It’s entirely possible that your calf pain is from nothing more than tight calf muscles themselves. This is quite a common cause of calf muscle tension/pain when performing hip hinging exercises. As such, I’ve saved it for last as it’s quite often a rather boring and straightforward process to get under control (by the way, when it comes to injury and pain rehab, boring is good).

As was mentioned in the previous section involving the hamstrings, the calves are prone to becoming tight and painful from the presence of trigger points within the muscle belly.

The calf muscles cross the back of the knee joint and can therefore produce sensations of tightness during the RDL since the knees are kept in a near fully extended position throughout the movement. The straighter the knee is positioned, the greater the stretch placed upon the calf muscles.

Dealing with tight calves

Assuming no other underlying causes, managing and treating calf tension can be performed in numerous ways. Some common treatment techniques you can perform by yourself include:

- Soft tissue massage

- Foam rolling (or barbell rolling — if you’re feeling brave)

If you want the details (and other self-treatment strategies you can try, check out my article: The Seven Best Ways to Massage Your Calf Muscles All By Yourself

Final thoughts

While it’s not necessarily unheard of to experience calf pain when performing an exercise such as the RDL, it’s not normal, either. Regardless of what might be causing your discomfort, you’ll want to work to get to the bottom of the issue. Doing so will not only get you out of pain, but it will also help ensure you can keep performing RDLs for all your days to come.

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!