The box squat can be your best friend for developing some serious lower body raw strength. It can also be your worst enemy for flaring up your back. No doubt, this powerful exercise needs to be performed with complete confidence and perfect execution. As they say, “with great power comes great responsibility.”

This article will walk you through navigating the issue of how and why lower back pain can occur from box squats, how to fix it, and how to make sure you can get back to performing this beauty of an exercise with total confidence.

Low back pain from box squats is often the result of excessive spinal compression, poor lumbar spine positioning, and inappropriate box height. Solutions are to use slow eccentric movement, improve your lumbopelvic awareness, and ensure optimal box height.

Now, I’ll be breaking all of this down in much more extensive detail, so keep reading if you want to know the details and strategies I often implement to clean up the issues in many of the lifters and active individuals I treat.

Related article: Deficit Deadlift Back Pain | Causes | Fixes | A Specialist Explains

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including low back pain with box squats. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

Quick reminders

As we dive into this article, please keep the following in mind:

Reminder 1: Using multiple strategies

There can be multiple factors contributing to one’s pain for an issue such as within this article; there’s no rule saying pain can only be the result of one specific factor or that only one specific structure or tissue in your body is being affected.

As a result, while you work through your back pain, you may find that you need (or can at least benefit from) multiple strategies and interventions, be it ones within this article or elsewhere. Take the necessary time (and the necessary patience) to find what works best for your back and body. The best lifters out there are the ones who are willing to take the time to tune into what their body is saying as they navigate pain and setbacks.

Reminder 2: Underlying issues

You might not necessarily have done anything wrong from the box squat itself to experience back pain; something else may have aggravated your back, and the box squats are taking the blame. It could also be that the box squats are contributing to your discomfort or pain but aren’t the underlying mechanism.

It’s also possible that the box squat took an underlying latent issue within your body and served as the “straw that broke the camel’s back” (no pun intended). Generally, I find there’s an outwardly evident issue that leads to the lifter experiencing back pain after any type of squat (be it a box squat or another type of squat).

If you feel that none of the following issues within the rest of the article are what caused you to have pain, you could be entirely right. If so, get some insight from a strength coach for anything that might be less than ideal with your technique, and consider getting a professional evaluation from a qualified orthopedic specialist to help you take care of your pain.

Common pain generators of the spine

Over a dozen different structures and tissues within the spine can cause discomfort or pain. I can’t cover all of them within a blog article. But I certainly can cover the basics of the most commonly affected tissues and structures of the back when it comes to squatting and lower back pain. So, let’s quickly go over some of the absolute basics.

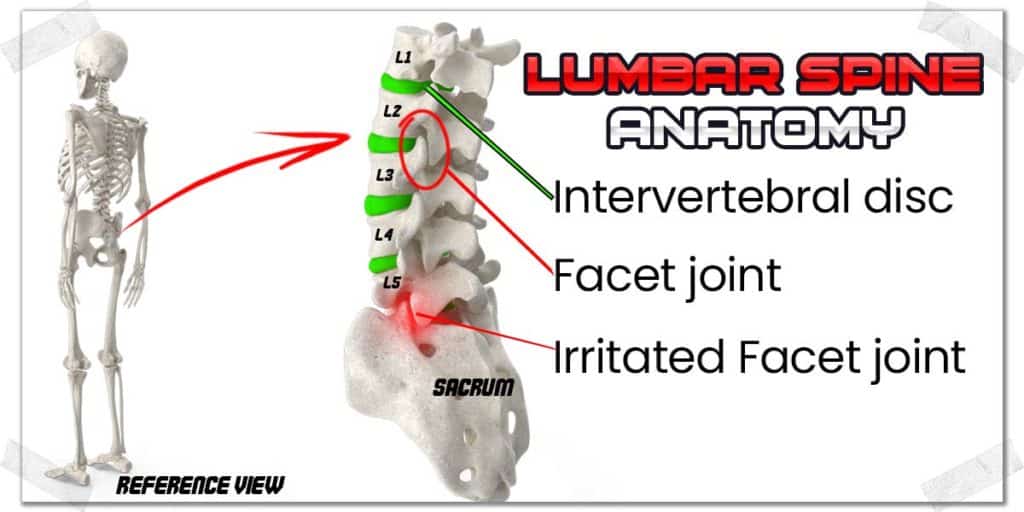

Intervertebral discs

The intervertebral discs are the little “hockey puck-like” structures sitting between each vertebra (spine bone) within the spine itself. They are made of fibrocartilage with a soft, jelly-like center (known as the nucleus pulposis).

Discs can become irritated, undergo derangement (bulge, extrude, etc.), or degenerate, all of which can lead to pain within the lower back, especially when the spine is compressed while being in a flexed position.1–3 You’ll learn more about this in the following sections.

Facet joints

The facet joints are what essentially “link” one vertebra to the next. It’s these joints that allow the spine to bend and move in its various directions. These joints are prone to becoming irritated if the spine’s positioning isn’t ideal throughout all phases of the box squat (discussed further on).

Nerve roots

All of the nerves in your extremities branch out from your spinal cord. Nerve roots are the first projection arising from the spinal cord that begins to carry the nerve out to the extremity or other areas of the body.

Nerve roots are prone to becoming irritated due to the narrow opening through which they pass. Issues with the disc or degenerative conditions can lead to encroachment onto the nerve, leading to pain and discomfort. This is has been shown to be especially common when the lumbar spine is held in a flexed position while sitting.4 So, you’re absolutely going to want to make sure you read the sections of this article pertaining to improving positional awareness and using optimal box height.

The SI joint

The sacroiliac joint (SI joint, for short) can be a common cause of pain in nearly anyone, and lifters are no exception. An irritated SI joint tends to produce pain that feels a bit more sharp and sudden in nature with specific movements. The pain is usually confined to a small region directly medial to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS).

Muscles of the low back

The main lower back muscles that most people think of or are familiar with are the spinal erectors, a group of superficial muscles that help keep our torso upright or even pull our torso backwards. While these muscles can become excessively stressed or strained (leading to muscle soreness), they won’t be the focus of this article as muscle strains of the spinal erectors from box squats doesn’t seem to be anywhere near as common as soreness from other tissues (at least, in my anecdotal lifting experiences and clinical experiences).

Issue 1: Excessive compression of the spine

As with most of my articles, starting out with the most common reason for one’s pain is my preferred starting point. With newer lifters, in the case of lower back pain from box squats, it’s very often from a lack of positional awareness or excessive speed when lowering onto the box, which can lead to repeated compression of the spine.

With weight loaded across the top of your spine, repeated, sudden compression from lowering your body onto a firm, stationary box at a quick rate can be irritating to the intervertebral discs and facet joints. These structures are essentially getting sandwiched between the bottom of the box and the weight resting across your upper back.

And if you think, “well, I can avoid all of this by just using a softer box or sitting on a padded surface,” you’re going to want to keep reading to see why this might not be the greatest idea.

Remember: The heavier your squat becomes, the more you need to ensure you’re minimizing any movement errors and subsequent excessive compression of your spine. The heavier a load is, the less forgiving the box squat will be if your technique isn’t dialled in to an absolute T.

Let’s look at two very common reasons for why this can occur and the solution to implement for each one.

Problem 1: Lack of positional awareness

You can’t exactly look behind you when squatting to see where your hips are in relation to the box; you need to rely on your brain’s ability to gather sensory feedback from your joints about what position you’re in as to how close or far away your butt is from the box. The ability of the brain to interpret positional awareness from feedback supplied by specialized receptors in the body is known as proprioception.

If you don’t know where the box is when lowering down onto it, you can get an inaccurate interpretation of how much further you can keep squatting down before contacting the box with your butt. As a result, you might be dropping your butt at a quick rate, thinking you’ve still got a few inches to go before coming near the bench. Then all of a sudden, without warning – BAM! – your butt hits the bench a bit harder than you thought. This can lead to quick but forceful compression throughout your lower back.

It might not even feel like much in the moment, but the discs and facet joints can be sensitive to these types of sudden compressive forces, especially when they occur rep after rep and set after set.

The solution for lacking positional awareness

If you’re squatting with relatively heavy loads for your abilities, you need to have supreme confidence in knowing where you’re hips are at all times in relation to the box. You need to have this proprioceptive ability dialled in perfectly, whether you’re just doing a “tap and go” box squat or a true box squat where you offload your legs entirely.

If you lack even the slightest bit of confidence, your best bet is to practice with just your body weight until you can hit fifty reps in a row of confidently stopping one inch above the box’s surface (to which you double-check by then dropping the last inch and confirming you were only one inch away from the surface).

Once you’ve got this down, make sure you can do the same thing with just the barbell across your back (or collarbone for front squats). From there, you’ll likely be good to go with your working loads.

Problem 2: Sitting on the box too quickly

Even if you have immaculate positional awareness at all times of knowing where your hips are in relation to the box, you can still be prone to sitting on the box at too quick of a rate. The quicker you sit onto the box, the more jarring the compression force can be through the discs and joints.

Again, it might even feel like you’re doing anything too aggressive in the moment, but sometimes there can be a delayed kickback between the body tolerating an activity within the moment versus how it responds a handful of hours later.

The solution: Use slower eccentric movement

If you’re not familiar with the term, the eccentric portion of an exercise (such as a squat) refers to the controlled lengthening of the working muscles. For the squat, this is the phase in which you’re dropping down by bending your knees and hips.

Slower eccentric movement will give your brain a better understanding of your positional awareness by giving it more time to interpret what’s happening position-wise with your knees and hips.

Not only can this can help with proprioceptive input, but it also ensures that you’ll be minimizing the jarring impact your spine might be undergoing by sitting onto the box as softly as possible.

Pro tip: A good cue to help you sit on the box as softly as possible is to make as little noise as possible in the process; the quieter your process of sitting is, the less sudden compression you’ll likely be running through your spine.

Should you use a softer box or surface?

Now, if you’ve made it to this point in the article and are thinking, “well, I’ll just sit on a soft, padded surface,” you might want to rethink this idea.

Assuming you’re doing a full box squat (i.e., resting your entire body weight on the box), a padded surface will rob you of your ability to produce the force necessary to fire out of the hole (bottom of your squat). This is simply because your body can’t transfer force when pushing off an object that is giving way in the process.

Think of it like trying to fire a cannon out of a canoe: without a firm, unyielding surface beneath it, the cannonball’s ability to fire at maximal speed and force will be adversely impacted.

Just take the time to master your ability to feel where your hips are at in space and to sit on the box as softly as possible. It will serve you better in the short and long term.

Issue 2: Poor lumbar spine positioning

Whether you’re sitting on the box or your butt just above its surface, proper lumbar positioning is critical at all points throughout your squat — it’s non-negotiable. This is especially true if you’re squatting with any decent amount of weight across your back (or across your collarbone if performing front squats).

Lumbar spine positioning: why it’s such a big deal

Anytime you have weight strapped across your upper back and perform a movement that involves repetition upon repetition, you want to make sure your back is in a position that provides maximal stability and minimal stress and strain to the involved tissues.

Ideal lumbar spine positioning for squats (box squats or any other type) requires a lifter to “stack” their lumbar spine in a position that ensures the vertebra will not move into a rounded (flexed) position.

Related article: Why Your Lower Back Hurts After Box Jumps | Errors | Fixes & Pro Tips

Lumbar discs

While it’s always a good idea to be mindful of this, even with lighter squats, it’s imperative to follow whenever you have a load across your upper back. When performing box squats, letting the spine move into a flexed or rounded position when either in the downward phase of the lift or while resting on the box can put you into a world of pain if you’re not careful.

Lumbar flexion with compression of the spine can place the lumbar discs in an extremely vulnerable position, which can lead to disc irritation or disc derangements such as bulges, herniations or even horrid conditions such as disc extrusions or disc sequestration.1–3 Any of these disc issues can lead to nasty symptoms such as sciatica or lower back pain, which can significantly impede your ability to lift and stay active.

Facet joints

As if that wasn’t bad enough, letting the lumbar spine move into a flexed position with a load strapped across your back is also a great way to irritate the snot out of your facet joints. The lumbar facets are like many other moveable joints in the body in that they have the capacity to be stressed and strained from repeatedly being placed into the end range of their available movement.

Think of it like pulling your pointer finger backwards as far as you can using your other hand; doing this repeatedly for multiple reps and sets for weeks on end can become quite irritating for the joint’s tissues.

The solution to poor lumbar spine positioning

If you’re not certain about whether or not you’re keeping your spine in a flat and strong position at all points throughout your lift, your best bet is to video yourself in the process and review it thereafter. Your other option is to have someone you trust to watch you perform your movement and let you know what’s going on.

If you can’t keep a perfect lumbar position at all times or develop the dreaded “butt wink” (more on that in the next session), you’re best off to practice controlling your spine throughout the squat without any weight up top on your spine.

Once you get to the point where you can control your spine movement perfectly and do so with very minimal amounts of mental effort, I’d advise you to proceed with getting back to squatting with weight.

Be disciplined about this. It’s not fun to ditch the weight or substantially lighten the load while you work on technique, but lifting is all about the long-term mindset; it’s hard to be a lifelong lifter or physically strong individual when you’re broken and wrecked from spinal pain.

Issue 3: Lousy box height

When it comes to putting box squats into your training regimen, there are plenty of reasons for lifters to use different box heights. Different heights can yield different advantages and benefits. But every lifter has a point at which the box becomes too low for their body’s abilities.

The point at which the box squat becomes too low is the point at which your lower spine must flex (move into a rounded position) to sit on the box.

This rounding of the spine results from all of the movement abilities within the ball and socket joint of the hip being used up. When the head of the femur (the ball) can no longer turn within the socket of the hip, the only way to sink further into the squat is through flexion of the lumbar spine.5,6

The solution to lousy box height

If you’re not sure whether or not your box is too low for your abilities, there’s a rather easy way to find the cut-off point for box height. Here’s how to do it:

- Find a mirror and stand in front of it but turn 90-degrees so that you can observe your body’s positioning from the side when squatting.

- Turn your head to look at the side of your body in the mirror as you begin to squat down. Squat very slowly while observing the positioning of your lower back. Make sure your lower back is in a neutral position.

- As you lower yourself down, look closely for the point at which your lower back starts to round (the point where your tailbone starts to tuck between your legs). This is the infamous “butt wink” and should always be avoided when you’re squatting with a load across your upper back (or collar bone, in the case of front squats).

- Once you find this point, grab a box and place it in front of the mirror. Repeat the above process, slowly lowering your butt onto the box. If you see the “butt wink” occur, the box is too low for ensuring a neutral lumbar spine throughout your box squat.

Keep all your future box squats in line with this height-measurement method once you’ve found a box that you can sit on at a height that doesn’t produce any butt wink. If you want to use a lower box, take some time to work on your hip mobility first. Once your hips are more mobile, you’ll be able to move deeper into your squat before the “butt wink” shows up.

Final thoughts

If you’re careful with your box squats, you can reap some massive rewards in terms of lower body strength. Conversely, if you’re not careful, you can reap some annoying setbacks, bet it a minor flare up to a chronic, rather debilitating issue.

Take the insight and tips within this article and use them as a general starting point for getting pointed in the right direction when it comes to getting to the root cause and tackling your pain. It can be an annoying or frustrating process, but one that is well worth it. Listen to your body and give it some love. Your spine will surely thank you, and you’ll likely be able to get back to squatting pain-free!

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!