Running or sprinting uphill can be a phenomenal way to challenge (and improve) various aspects of your physical and cardiovascular fitness. But it’s hard to do when it makes your calves chronically sore, tight and feeling otherwise lousy. Thankfully, getting the issue under control (while ensuring it never happens again) is often a relatively straightforward process.

Calves are more prone to soreness after running up a hill due to the high stretch the muscles and Achilles tendons must undergo while exerting much greater effort to push the body uphill. The result is a much more intense mechanical demand on these tissues than when running on flat ground.

So, while soreness from this activity is quite normal, doing all you can to minimize it will lead to better training sessions and less risk of physical injury.

The solution, therefore, is to ensure you have three factors dialled in:

- Proper training volume (you can calculate it if needed)

- Proper recovery methods for your muscles

- Proper loading protocols for the muscles and tendon

If you want the expanded details on these factors, keep on reading!

ARTICLE OVERVIEW (Quick Links)

Click/tap any of the following headlines to instantly read that section!

• Calf & Achilles’ tendon anatomy

• Why the hills hurt

• Mistake & solution 1: Training volume

• Mistake & solution 2: Proper recovery methods

• Mistake & solution 3: Basic loading exercises

Related article: The Seven BEST Ways to Massage Your Calf Muscles All By Yourself

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not any treatments or training methodologies mentioned on this website or in this article may or may not be appropriate for you, including treatment for your calves or Achilles tendon. By following any information within this post, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical advice for any pain you may be experiencing.

Calf & Achilles tendon anatomy

An introductory understanding of anatomy will go an incredibly long way when it comes to helping you achieve higher success with reducing (and ultimately avoiding) the sore and tight sensations that you’re likely experiencing from running or sprinting up hills. There’s good scientific evidence to show that individuals who better understand their pain have better outcomes as they work towards their recovery.1-4 So, let’s quickly go over the basics.

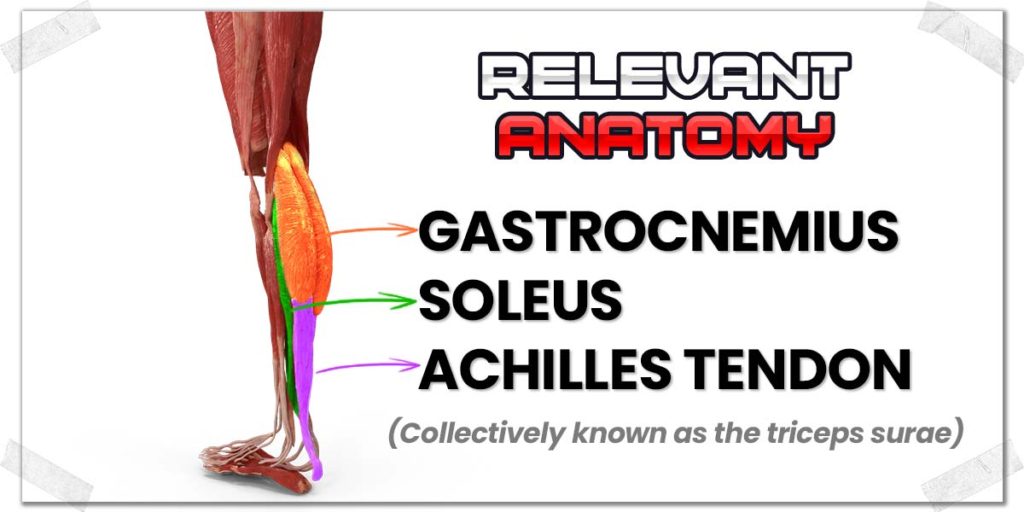

The calf and soleus muscles

The two particular muscles on the back of the lower leg that are of significance with this article are the gastrocnemius muscle (AKA the calf muscle) and the soleus muscle. The gastrocnemius comprises two individual muscle heads, known as the medial and lateral head. The combination of these two heads and the soleus collectively make up what’s known as the triceps surae.

The gastrocnemius and the soleus muscle are of particular interest here since both of these muscles attach to the Achilles tendon, which ultimately attaches to the calcaneus (AKA the heel bone).

The Achilles tendon

The Achilles tendon is a thick, gristle-like structure that connects the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles to the heel bone (the calcaneus). As a result, it transmits the forces exerted from the muscles down to the heel, pulling the heel upwards (which pushes the forefoot downwards).

Like any other tissue in the body, the Achilles tendon can become stiff, overworked and otherwise unhealthy. As a result, it can adversely affect the health of the muscles it attaches to, which can lead to soreness, tightness and discomfort either in the tendon itself, the muscles, or both.

The function of the triceps surae

The gastrocnemius, soleus, and Achilles tendon provide the lower leg with the ability to plantarflex the ankle — this is the movement of pushing your ankle downwards (as if stepping down on the accelerator pedal in your vehicle). In this position, the muscles are contracted (shortened).

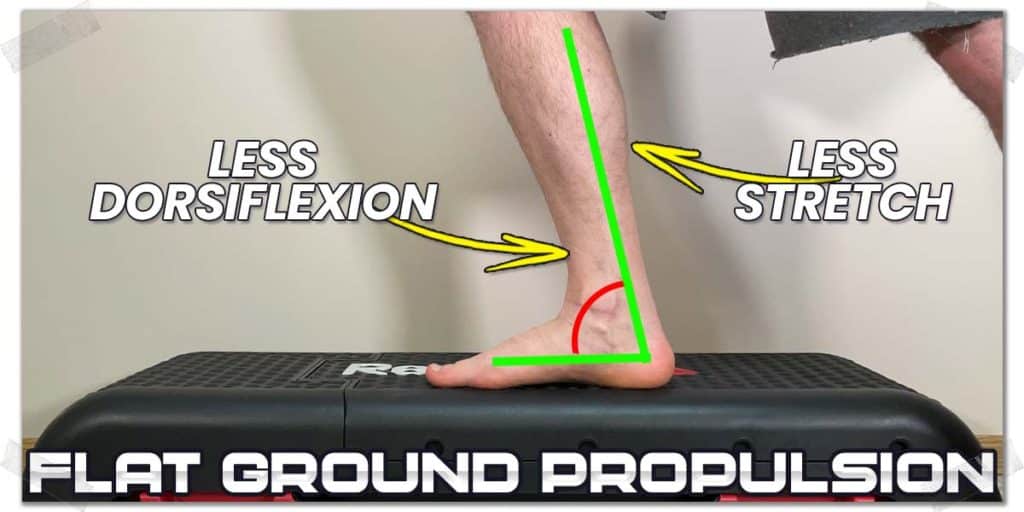

The opposite of plantarflexion of the ankle is dorsiflexion — the pulling upwards of the foot. In the dorsiflexed position, the triceps surae is in a stretched-out or lengthened position. This is the position that the ankle is repeatedly subjected to when running or sprinting up a hill.

Why the hills are hurting your calves

Now that you have a basic anatomical understanding of the calf muscles and Achilles tendon, we need to ensure that you have a solid grasp on understanding why (and how) running or sprinting up a hill places different biomechanical demands on these structures.

The quick takeaway:

Running up a hill places a much more significant amount of stretch on the gastrocnemius, soleus and Achilles’ tendon since the body must lean forwards. At the same time, the ankle must simultaneously dorsiflex to a greater extent. Each of these factors dramatically increases the physical demand transmitted through these tissues.

If you want an expanded explanation of why this happens, you can read either the non-geeky (basic) or the geeky (technical) explanations below. And, if you’re a real keener, you can read both!

The non-geeky explanation for your discomfort

Being required to produce high amounts of contractile force — while doing so from a stretched position — places a drastically increased amount of mechanical stress and physical demand into the muscles and tendons to which they attach.

Running or sprinting up a hill will require your calf muscles and Achilles tendon to work in a different (more aggressive) manner than when running on flat ground. If your calf muscles aren’t used to the extra demand placed upon them during a hill run, it’s like doing a weightlifting workout with a bunch of extra weight than what you’re otherwise used to, which means you’re bound to feel sore as a result.

RECAP:

● If your calves, soleus, and Achilles tendon are stiff and have poor flexibility, they will be more sensitive to moving into a stretched position when running uphill.

● If your calves, soleus, or Achilles tendon are deconditioned (weak), they will be more sensitive to the intense demands required of them to physically propel you uphill.

A simple conceptual example

Think of it this way: Imagine holding a rather heavy dumbbell or weight in each of your hands. Now, imagine your left arm is straight down by your side while the right arm is bent to 90 degrees. Which would be easier to curl up to your shoulders: the weight in your left arm or your right arm?

It would be much easier (try it for yourself, if needed) to curl the weight in your right arm rather than the left. The reason is that your bicep in your left arm is stretched out to the point where the muscle fibers will have a significantly harder time generating the contractile force required to curl the weight up to your shoulder. The bicep in your right arm isn’t stretched as much in the 90-degree position and thus won’t undergo as much physical stress or mechanical strain.

The geeky explanation

Forcing muscle tissue to contract (shorten) from an extremely lengthened position results in greater inefficiency within the muscle due to a non-optimal amount of overlap between the actin and myosin filaments. Actin and myosin are the contractile proteins within the muscle that, when linking together, provide the muscle with its ability to contract and thus, shorten.

For a muscle to produce maximal force, it must have an optimal amount of overlap between these two filaments; the more stretched apart these two filaments are from one another, the less force it can produce.

If you want even more information on tendon biomechanics, check out this great article on physio-pedia.com

As a result, the muscle must work harder to produce the force required to contract (moving out of the stretched position) and obtain a more optimal overlap. So, if the muscle must do this against a high resistance (such as your entire body weight), it can be extremely taxing, leading to muscular soreness after a physical activity session.

Mistake 1: Excessive training volume

For many individuals, the underlying cause of their tight, sore or even painful calves that occur from running up hills is simply from doing more than their muscles and Achilles tendon can happily tolerate. This can come in the form of running your hills too many times throughout the week, running hills that are too steep, running up the hills too quickly, or any combination.

Related article: How to K-tape Your Achilles Tendon All By Yourself

Regardless of the specific offending culprit, the result is the same: calves that are overworked and leading to stiffness, discomfort or even pain.

The solution

If your calves are getting chronically tight and sore every time you do any hill running or sprinting, the first step to take is to alter your training volume (for the time being), as this will ensure you’re not making the issue any worse while also avoiding unnecessary predisposition to injury.

Training volume, in this context, refers to the amount of time or energy you’re spending on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis running uphill.

Session training volume = sets x distance x intensity

Weekly training volume = sets x distance x intensity x sessions per week

This doesn’t necessarily mean that you should avoid running uphill altogether; rather, you limit the weekly frequency you perform this specific activity, limit the intensity of the running, the distance or time spent running uphill, or any combination of these factors.

Pro tip: Dialling down the training volume one variable at a time can also help you determine which factor of your hill running is leading to your soreness. For example, if you reduce your hill running or sprinting to six sets per session down from eight sets, and you notice a drastic reduction in soreness, it might indicate that you’re simply doing a few too many sets than what your calves can happily tolerate.

Take some time to experiment with the various factors that Once you dial in a training volume that seems to keep your soreness in check, you can then slowly ramp up your training volume until it’s back to where you want it, allowing your calves to adapt along the way without being overloaded in the process.

Mistake 2: Neglecting recovery methods

If you’re pushing your calves hard (especially if on a regular basis), you need to ensure that you’re giving them the proper love and care they require to keep them happy and operating at full capacity.

Unfortunately, many runners make the mistake of putting their calves through the wringer with all of their hill running and then simply carry on with their lives without giving their calves any sort of recovery interventions. This can be a critical oversight, as proper recovery interventions can ensure more adequate health and function of these muscles.

Related article: Six Benefits of Using an Acupressure Mat for Your Aches and Pains

The solution

If you’re serious about taking care of your calves and not having to worry about the tight, sore sensations that can arise after your hill sessions, you’ll need some effective post-activity recovery interventions that you can implement.

There’s a whole world to explore here, but here are some general starting points:

- Consider doing some direct, soft-tissue work to the muscles and even the tendon. Lots of ways this can be done, but foam rolling is a great strategy to use.

- Consider placing some heat over the muscles rather than ice. While ice might feel nice, it likely won’t provide any physiologic effects for decreasing tightness — and it will likely only make things feel stiffer since cold temperatures make it harder for tissues to move.

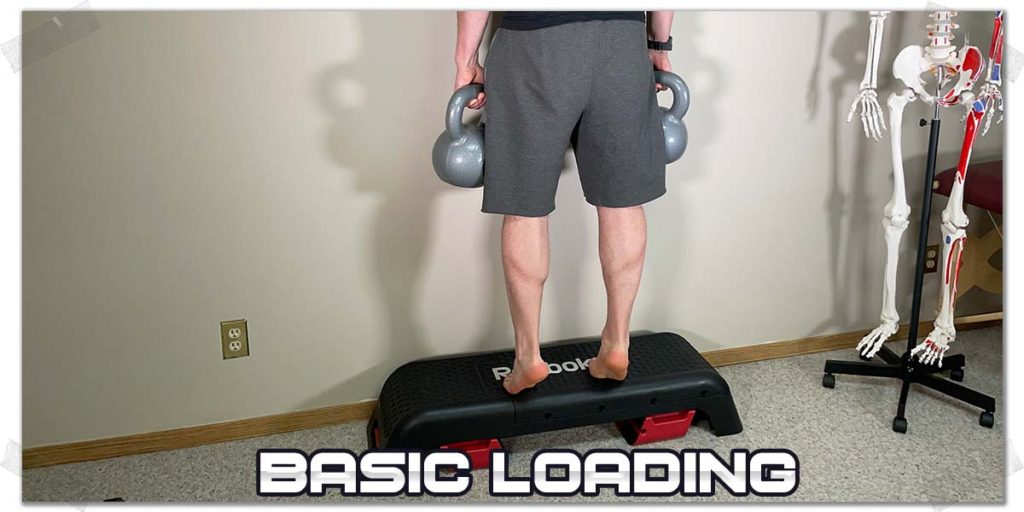

Mistake 3: Not incorporating basic loading exercises

It’s hard for your calves and Achilles tendons to endure the repeated stresses of running up hills when they lack adequate strength for the demands you’re giving them. And if you’re thinking, “well, I’m strengthening them by running up all these hills,” you’re correct, in a sense, but not entirely.

Running or sprinting produces sudden, high forces on the Achilles tendon. Additionally, when you think about the number of steps or strides you take in a single session (often in the thousands), there’s a high emphasis on endurance that the muscles and tendons must adapt to. The problem is that both endurance and strength are required for optimal muscular and tendon health.

The solution

Loading your muscles and Achilles tendon a couple of times a week through dedicated resistance exercises is a move that would be prudent of you to make.

When performed in a slow, controlled manner using a moderate-to-high level of resistance, these loading movements strengthen the muscle and tendon differently than the fast, high repetitive demands of running.

It doesn’t have to be anything complicated. Here are some solid exercises that you can use to load your muscles and tendons to improve their overall health, which can help reduce soreness and tightness incurred from running up hills.

- Standing calf raises (biases the gastrocnemius muscles)

- Seated calf raises (biases the soleus muscle)

Here are some general parameters I would recommend for a strengthening/loading protocol for your calves:

I would advocate that each complete repetition that you perform take around three seconds. This will require much more dedication on your part to adhere to but will likely elicit a much more effective stimulus to the tendon and muscles when it comes to improving their strength and physical health.

Final thoughts

Running or sprinting up hills is an outstanding way to improve various aspects of your physicality. Still, if it’s taking a toll on the health of your calves, you’ll need to step back and learn why they’re becoming sore, tight or otherwise painful. Once you better understand why this is all occurring, you can implement some of the solutions in this article.

Take the time to find the underlying causes of your calf soreness and then commit to finding and sticking with the appropriate solutions. It may take some time, but if you’re diligent, you’ll get back to where you want to be — running up the hills with calves that can take the demand of every step that you take.

References:

4. Butler DS. The Sensitive Nervous System. Noigroup publications; 2000.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!