This article will give you expert insight into why individuals often experience neck pain during or after their squats and what can be done to fix the issue. The end result will be stronger legs and a healthier neck. So, read through the contents below if this sounds like what you’re after!

Neck pain during or after squats is often the result of poor joint mobility in the spine, excessive muscle tension in the upper body, poor bar placement and lousy mechanics. Solutions involve optimizing joint health, improving upper-body mobility and refining your squat technique.

Each of these topics will be broken down in detail, which will allow you to better understand what’s causing your pain, and why the solutions I present for each issue can be so effective.

A quick request: If you find this content to be helpful, please consider sharing it on a social platform; it takes a lot of time and effort for me to craft these articles (but I love doing it), and a share would mean the world to me and help support these pursuits!

Pain generators & causes of pain

Before diving into the common squat-technique errors that often contribute to neck pain, a basic rundown of neck and upper back anatomy is essential.

Trust me when I say that a basic understanding of the involved anatomy contributing to your pain will make a profound difference in your ability to resolve the issue; it will make the required steps much more intuitive while also ensuring you minimize the chances of accidentally or unknowingly making the issue any worse.

After all, not all of your neck pain may be from squats, so talking only about squats and subsequent technique errors is likely only part of the battle.

Therefore, I’ll provide some general starting points for getting any pain or discomfort under control, regardless of the cause.

After that, I’ll dive into common technique errors that can increase neck pain when squatting and how to best resolve said technique issues.

Basic neck anatomy

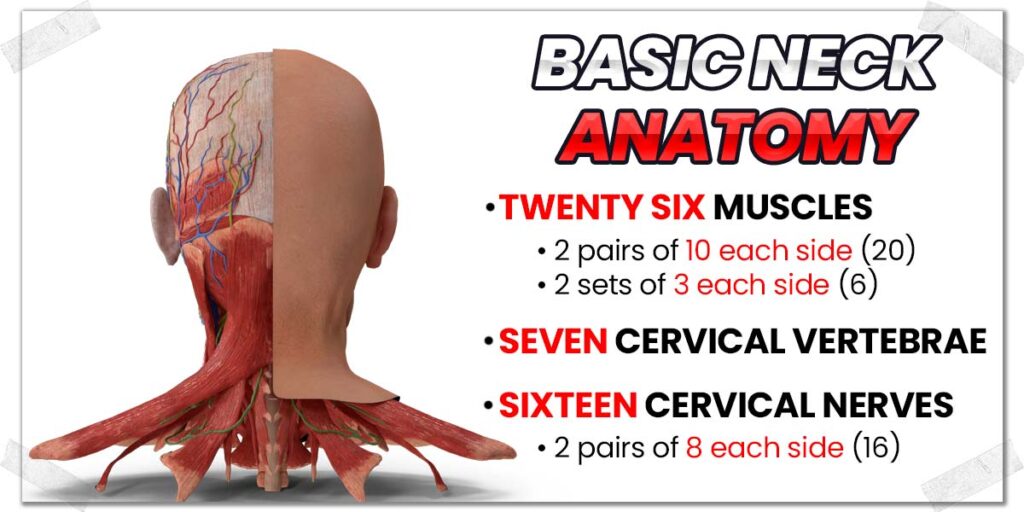

The neck is a rather fascinating area of the body; there is an extensive amount of highly specialized muscles and various other tissues jam-packed within a very small area. For the sake of this article, I’m considering the neck to be the area between the base of the skull and the top of the shoulder region.

In terms of orthopedics, within the neck, you’ll find:

- 13 pairs of muscles

- 7 cervical vertebrae

- 8 nerve roots exiting out each side of the spine

As such, a lot can go wrong within a small area. Let’s quickly go over some of the more commonly sore, irritated, or painful structures within the neck and the type of pain they tend to create.

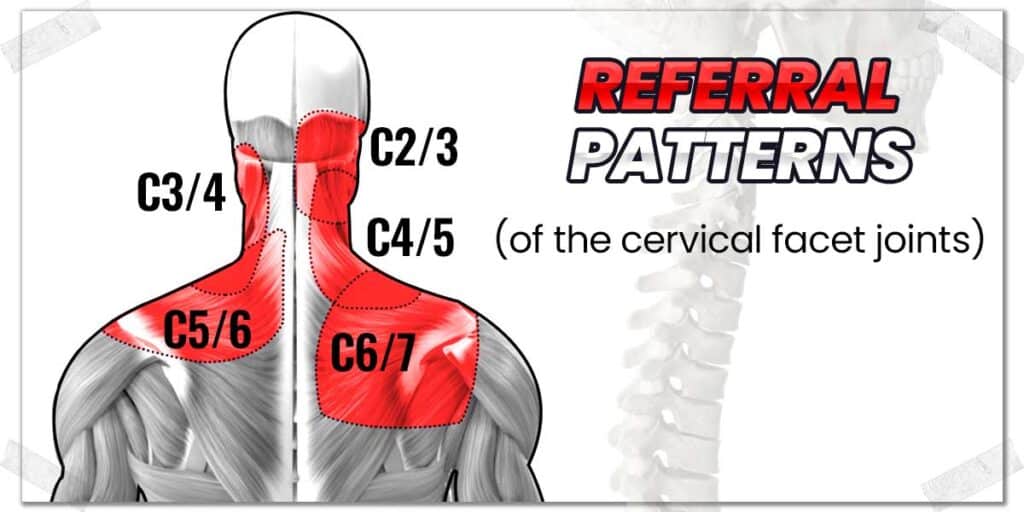

Facet joints & facetogenic referral patterns

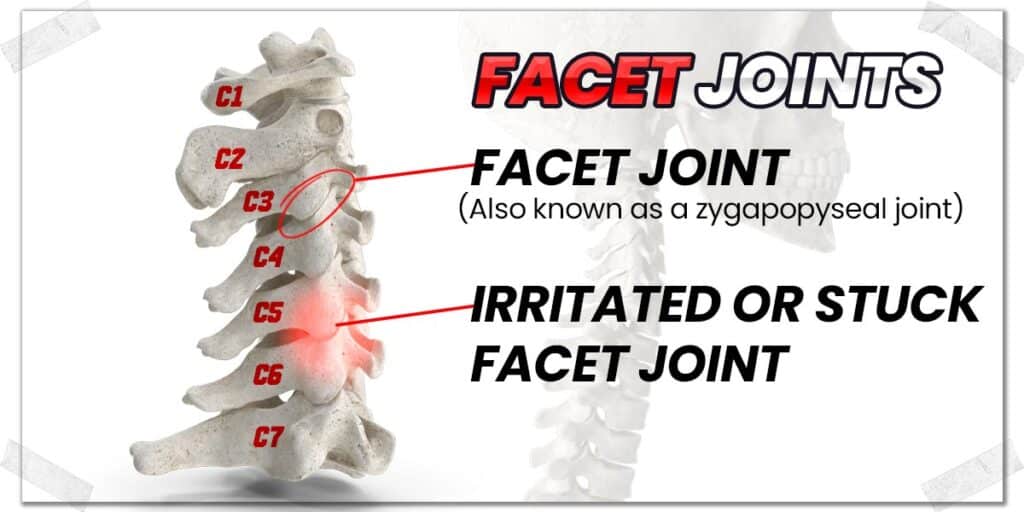

The facet joints are the joints in your spine that link one vertebra to the next. Each joint is about the size of your fingernail, and these joints are responsible for sliding and gliding on one another when moving your neck.

Facet joints can be common sources of neck pain; they can become stiff, stuck, irritated, or arthritic, all of which can lead to pain and discomfort when producing neck movements or holding the neck in a specific position.

Facetogenic pain (pain arising from the facet joint) tends to produce discomfort or pain that’s more focal and sharper in its sensation, unlike muscle discomfort, which is usually more of a dull and widespread sensation of discomfort.

Solutions for facet joint pain

If your neck pain is the result of one or more facet joints, you’ll want to get to the bottom of the issue. This typically involves working with a qualified orthopedic specialist (such as a physical therapist) to restore their mobility and perhaps correct the underlying cause of their dysfunction.

Additionally, you’ll want to make sure you try and perhaps implement the technique changes described later on within this article.

Cervical discs & Cloward’s referral patterns

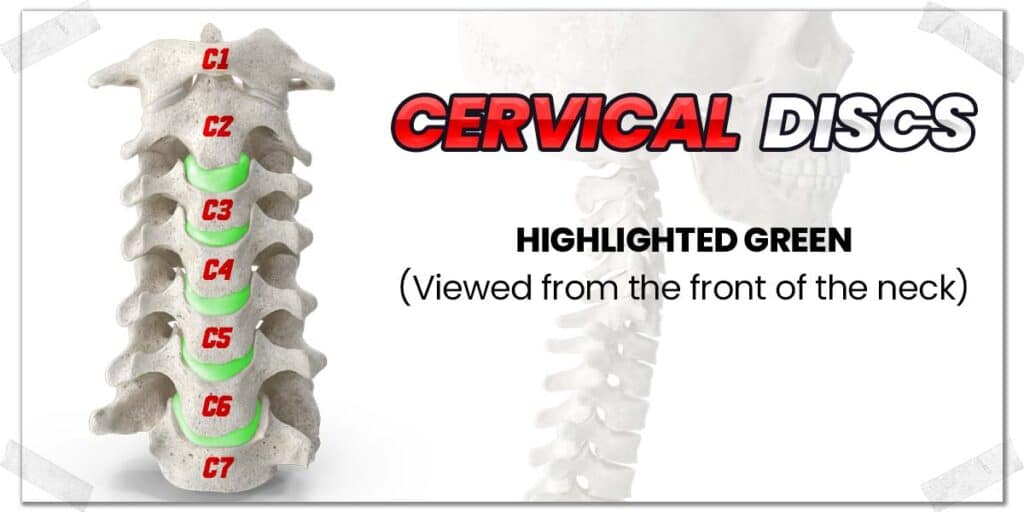

The cervical discs are the hockey puck-like structures that sit in between each vertebra (spine bone). They help to provide the neck (and the entire spine) with better structural integrity and tolerance to everyday life.

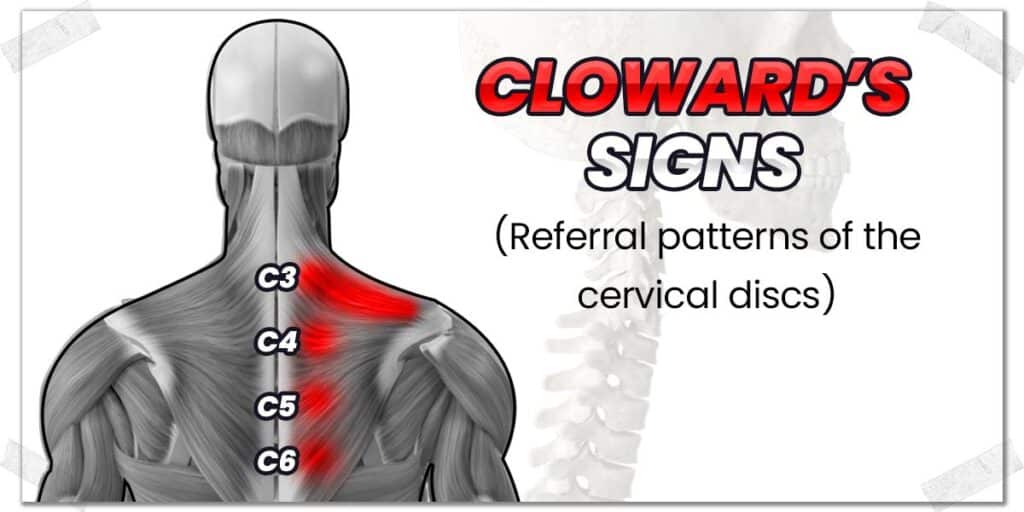

The cervical discs are prone to becoming unhealthy in various ways (they can become irritated, deform, degenerate, etc.), all of which can lead to pain that’s felt either in the neck or even between the shoulder blades (known as Cloward’s sign).

Pro tip: Sometimes, the cervical discs can bulge and deform in ways that press on one of the nerve roots exiting from the spinal column. This is often referred to as a “pinched nerve” and can be very painful, even sending pain or electrical twinges down the arm. It’s also commonly seen with arthritic and degenerative necks, resulting in a condition known as cervical stenosis.

Solutions for disc issues

Just as with facet joint issues, it can be a good idea to work with a qualified professional who can help ensure that the pain is, in fact, arising from the disc(s). You’ll likely want to try some home traction, which can help alleviate pain, especially if you’re getting any paresthesia (numbness or tingling) down into your arm.

Muscles & myalgic discomfort

It’s entirely possible to experience muscle discomfort in your neck while doing everything right with your squats. As such, if your neck generally feels tight, stiff, or achy even when you’re not squatting, it could simply be due to lousy health and function of some of these muscles.

With so many muscles in the neck, it’s not uncommon for muscle tension to arise, which can absolutely lead to sensations of aching, stiffness, or generalized soreness being felt anywhere within the neck.

Some of the more commonly affected neck muscles include:

- The upper trapezius fibers

- The levator scapulae

- The suboccipital muscles

- The scalenes

When muscles become overworked or endure chronically poor posture, the result can be generalized muscle dysfunction (meaning the muscle isn’t working properly). Muscle dysfunction not only impedes a muscle’s ability to work properly but also tends to produce discomfort or pain, particularly when movement is taking place.

Solutions for muscle discomfort in your neck

Generally speaking, there are a handful of different actions you can consider taking to get your neck tension under control.

Your first priority, as always, is to get to the root cause of the issue. For many people, this neck tension is the result of poor posture. One of the most common postural issues that causes neck pain is upper crossed syndrome, a condition where certain neck muscles become chronically tight while others become chronically weak.

Working on strengthening the weak muscles will help relieve the tension in the tight muscles.

Related content:

Additional strategies for helping muscle discomfort in your neck can include:

- Heat (hot packs that wrap around the neck tend to feel quite nice)

- IASTM performed by a qualified practitioner

- IMS treatment performed by a qualified practitioner

The thoracic spine

The thoracic spine is the region of the upper back beneath the cervical spine (but above the lumbar spine). While it’s anatomically a separate region of the body, from a functional perspective, the top two thoracic vertebrae can be considered part of the neck (since these two vertebrae also move when the neck moves).

If your thoracic spine is stiff and tight (which can be due to the joints or the surrounding muscles), it can absolutely lead to aches and pains in your cervical spine (your neck).

The less your thoracic spine moves, the greater the cervical spine will have to move as a means to compensate. This can lead to excessive mobility arising in the cervical spine, particularly at the C5/6 joint.

Solutions for poor thoracic spine mobility

It’s not uncommon for individuals to experience stiff, tight upper back regions, even without squatting. So, don’t make the mistake of thinking that your upper back stiffness is the result of poor squat technique.

Giving your thoracic spine some love can go a long way here. The easiest way to go about this (if you’re keen on doing things on your own) is to perform some foam rolling exercises on your upper back.

Rolling your upper back will help mobilize and loosen the thoracic facet joints (you may even get a pop or two out of the joints, which is known as joint cavitation).

Additionally, the pressure of the roller can help massage and relax the muscles of the upper back region, so it really is a two-for-one technique!

Additional exercises that are easy to implement and highly effective at restoring thoracic mobility are the cat/cow and open books.

Cat/cows will work to mobilize the thoracic spine into flexion and extension, while open books will restore rotational mobility (which feels amazing, by the way!).

If you want specifics on these exercises, you can easily Google them or watch my YouTube video above (and the warmup video below) for more exercise insight on thoracic spine mobility.

Technique errors & solutions

Neck pain from barbell squatting is often quick to arise if your technique is off. As I dive into common technique errors, I’ll start off with the “low hanging fruit,” meaning I’ll start with the issues that are often the quickest and easiest to resolve. From there, I’ll progress into the issues that tend to take a bit more work and effort to resolve.

Technique issue 1: You’re just not used to it

If you’re new to barbell squatting and placing the barbell across your upper back feels uncomfortable, or the pressure of the bar isn’t comfortable, you’re not alone; this issue is very common with newer lifters. (I remember going through it myself when I first started to lift back in high school).

This isn’t a technique issue, per se. Rather, it’s more of a “welcome to the world of lifting” greeting from the barbell. Even if your barbell placement is perfect (more on that later, if it isn’t), it’s often uncomfortable on newer lifters for two reasons:

- Placing a weighted object across one’s upper back isn’t something newer lifters are accustomed to. As such, it’s an awkward and uncomfortable feeling in the initial stages of learning to lift.

- Newer lifters may not have as much muscle mass (acting as natural padding) on their upper back, which can certainly alleviate the discomfort of a metal bar otherwise resting on top of some bony areas beneath the skin.

The solution here is to give it a bit of time to get used to the feeling, provided it’s not actually painful.

You can also opt for using a dedicated barbell pad, which wraps around the barbell, acting as a cushion. These are commonly found in gyms and are a common solution for newer lifters or for those who just can’t tolerate the pressure of the barbell resting on the back.

Pro tip: You can easily make your own barbell pad (for dirt cheap) by cutting a pool noodle down to length and then cutting it lengthwise. It will wrap around the barbell perfectly and act as an effective and very inexpensive barbell pad.

Technique issue 2: You’re not looking straight ahead

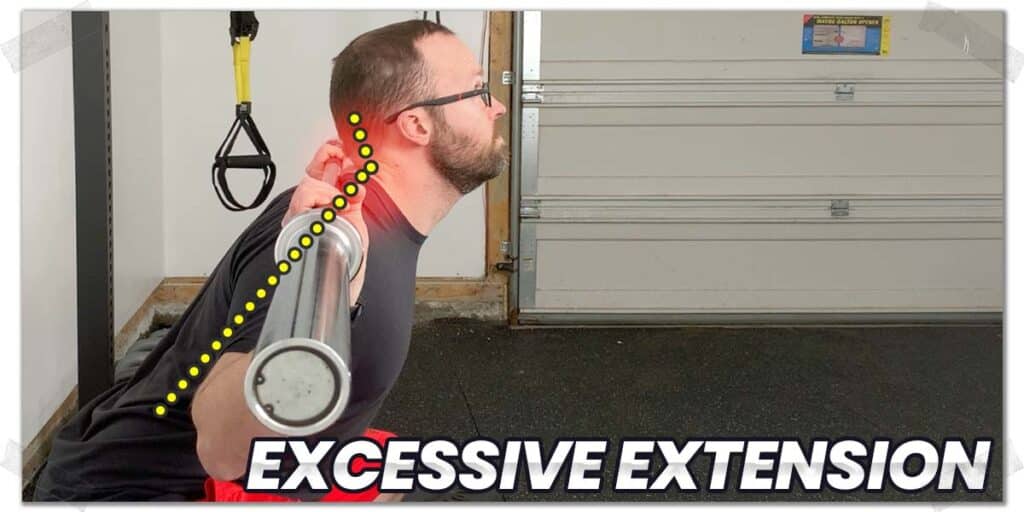

Too often, I see athletes and individuals perform their squats while trying to look upward. While there’s no universal, absolute “right or wrong” when it comes to neck positioning during your squats, it’s a good idea not to look upwards.

For most people who have an otherwise healthy neck, it’s not a problem to tilt your chin upwards (look up) when squatting. The problem is that not everyone has a super healthy neck to begin with.

Looking upwards (particularly when at the bottom of your squat) forces the neck to go into a significant amount of extension, which can be irritating to your facet joints. This is especially true if you do this over and over again, rep after rep, set after set, month after month, etc.

The solution here is pretty simple: Keep your neck in a more neutral position throughout the squat. You can do this by staring at the wall directly in front of you or by even looking slightly downwards.

This will keep your neck out of extreme ranges of extension, which will hopefully help reduce or eliminate any neck pain you may be experiencing.

Technique issue 3: Poor bar placement

If you’re new to squatting, it may feel a bit odd to rest a barbell across your back, and as such, you might not be using ideal bar placement. Newer lifters often make the mistake of resting the barbell too high up on the base of their neck, and this can be extremely uncomfortable.

If you bend your head forwards (bring your chin to your chest) and run your hand down the base of your neck, you’ll feel a large bump at the base. This is the spinous process of your seventh cervical vertebra (C7).

The barbell should always rest beneath your C7 vertebra. Resting it on or above this spot can be extremely uncomfortable and adversely affect your squat performance.

So, how far beneath your C7 should you rest the barbell? Well, there are two barbell positions that can be utilized for squats: the high bar and the low bar position. Let’s look at each to help you know which one may be best for you.

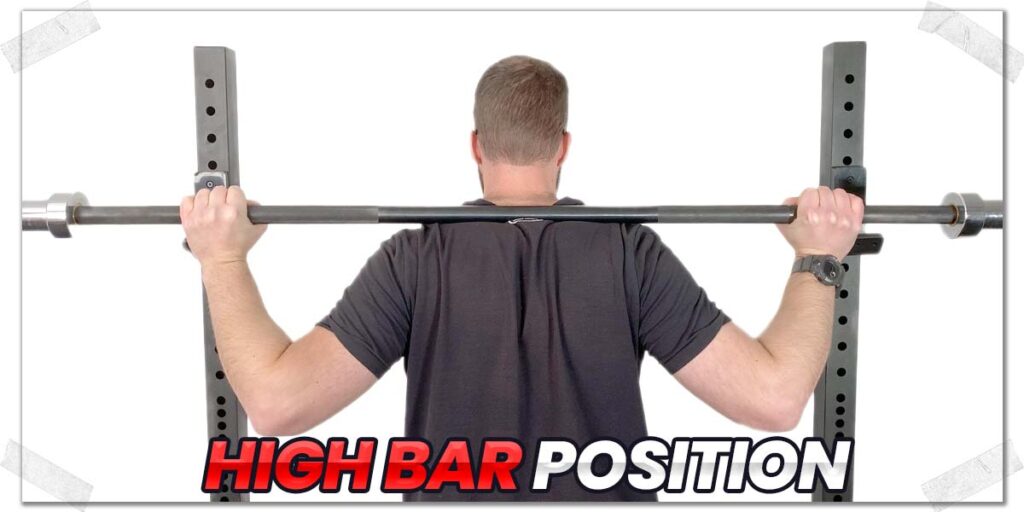

High bar placement

The high bar squat is by far the most common bar placement for gym-goers. This position involves placing the barbell directly beneath the spinous process of the C7 vertebra. It requires much less upper body mobility (particularly through the shoulders) than the low bar squat.

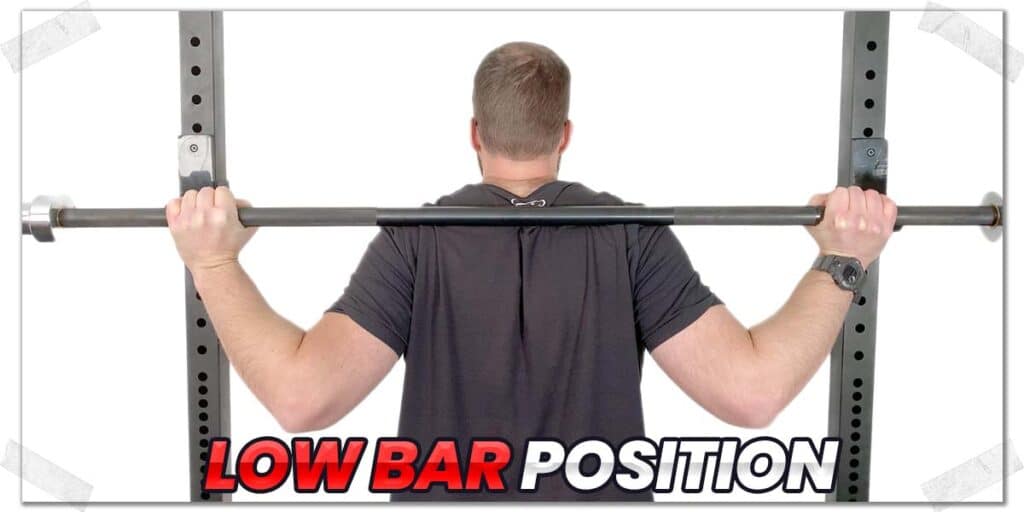

Low bar placement

The low bar squat is more commonly employed by powerlifters and other competitive individuals competing in strength-based sports. As the name implies, the low bar technique involves resting the barbell lower down than when compared to the high bar placement. Typically, the barbell will rest between the second and third thoracic vertebrae (T2 and T3).

Neither bar placement is universally “better” than the other; rather, it’s about learning which placement is most ideal for your needs and abilities.

As an example, while I can certainly low-bar squat and find that I’m perhaps more stable this way when squatting heavy, my default is high-bar squatting. For my needs these days, it simply works for me and is what feels most natural and comfortable for my body.

Final thoughts

Necks can become painful for numerous reasons and in all sorts of ways. Whether you’re new to squatting or a seasoned veteran, neck pain with this exercise isn’t normal. Check your technique, give your body some healthy therapeutic movements, and work with a qualified healthcare practitioner, if needed, to get your neck back on track.

May your squats be heavy, deep, and pain-free!

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!