If one or both of your hips are giving you all sorts of aches and pains after working out (or after any other type of physical activity sessions), you’re not alone; this is a rather common issue faced by many active individuals (including myself). So, I’ve written this article to help you understand the common causes for why this happens and what can be done to remedy this rather annoying (and sometimes painful) issue!

Hips can ache after a workout for many reasons. It’s often due to tendinosis in the gluteal tendons, bursitis of the hip, labral issues, hip arthritis, or issues with the lower back. Specific solutions exist for each of these issues and are discussed within this article.

With all of the structures and tissues around the hip region, it can be a bit overwhelming for the average individual to try and sort out what’s happening. I see this often with my patients, so let’s look at everything in a simple, easy-to-follow format for the most common scenarios that can make a person’s hip ache.

Related Content:

As we get going with the content, please remember that I can’t address every possible cause of hip pain within a single blog post. But since common things are common, I believe it’s worth focusing on the issues that are more likely to arise than those that aren’t.

Please also keep in mind that your best bet for resolving any hip pain or discomfort you may be experiencing during or after exercising (including your hip aching after a workout) is to get a professional evaluation from a qualified specialist (such as an orthopedic physical therapist). What follows below is for informational purposes only.

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

Alright, let’s dive in!

Issue 1: Tendinosis of the glute medius and glute minimus

I’m starting this article with this particular issue since it is incredibly common and is almost always reported as an aching sensation around the hip (which is often more prominent during or after a workout or physical activity session).1

Tendinosis refers to a generalized state of poor health within a tendon (a tendon is a structure that connects one end of a muscle to a bone).

Tendinosis is characterized by the changes in the structure of the tendon, where the collagen fibers (a structural protein) no longer run in a nice, parallel fashion alongside one another and instead start exhibiting more of a crimped or non-uniform structure (which is only seen under a microscope).

When these changes occur, the tendon becomes compromised in its health and functional abilities, leading to aching around the hip, tightness, and generalized hip discomfort.

Tendinosis vs tendonitis of the hip

You’ve probably heard the term “tendonitis” before. It’s a very similar condition marked by inflammation of a tendon, which often arises when the tendon becomes overworked. It can be rather painful and even debilitating at times.

Tendinitis is a very short-lived issue that quickly progresses into tendinosis. As such, tendonitis is actually much less common than what the scientific community used to believe.2,3 If your aching hip condition is the result of an unhealthy tendon (or tendons) and has been going on for more than a few weeks, it’s likely tendinosis at this point.

That all might seem a bit technical, but it’s important to understand since treating tendinosis (which is far more common) typically involves therapeutic exercise to rehab the tendon back to full health.

Fun fact: The term “tendinopathy” is an umbrella term for describing a painful or unhealthy tendon. Both tendinitis and tendinosis are sub-categories of tendinopathy.

Signs and symptoms of tendinosis in the hip

Those afflicted with tendinopathy will often report soreness, tenderness, or aching in the general region of the tendon. A sensation of increased tenderness or soreness is often reported when palpated (pressed or felt) with their hand.

The discomfort can often be intermittent in nature; it may feel fine during the day or with regular activities but become notably worse after prolonged lack of movement (laying on the couch, in the middle of the night, etc.,) high volumes or intensity of physical activities (such as working out) or with repetitive movements.

Common hip muscles affected by tendinosis

Tendinosis of the hip muscles is relatively common. It often affects the bigger, more prominent muscles of the hip, including:

- The glute medius

- The glute minimus

- The psoas

- The upper (proximal) hamstrings

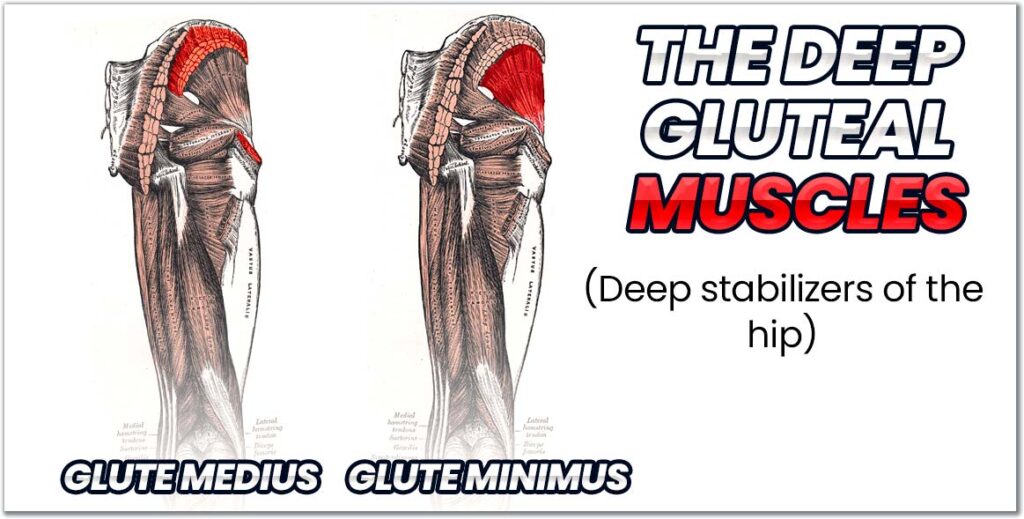

The glute medius and minimus

The glute medius and glute minimus are two muscles on the side of the hip that play a critical role in stabilizing the hip and pelvis when standing and walking. Without these muscles, balancing on a single leg while keeping your hips level is pretty much impossible.

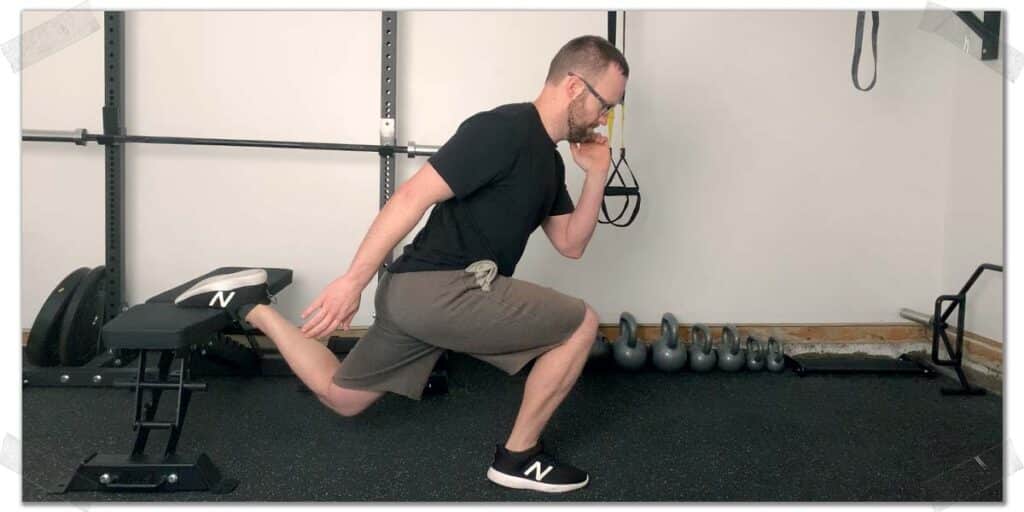

It’s quite common for either (or both) of these tendons to become unhealthy. When in this state, they don’t have the capacity to endure repeated demands in the gym or with other physical activities (squatting, lunging, running, etc.)

As a result, they are easily worked beyond their capacity, leading to aching, soreness, or even pain anywhere along the tendon.

If the glute medius and glute minimus muscles themselves are not strong enough, they can tire out very quickly when exercising, making the muscles tight and sore as well.

This is one of the most common conditions I treat as a physical therapist in our orthopedic clinic.

You can check out my YouTube video below for some outstanding exercises that can really light up these muscles, making them outstanding hip rehabilitation exercises for certain populations.

The psoas muscle

The psoas muscle is the large hip flexor muscle that most people think of when talking about tight or sore hip flexors. The distal psoas tendon is actually the combination of two particular muscles that converge to form the tendon. These muscles are:

The resultant common tendon is often called the iliopsoas tendon.

- The psoas

- The iliacus

This tendon can also become unhealthy, making it painful or uncomfortable to perform exercises involving hip flexion, such as running, traditional sit-ups, leg raises, etc.

The upper hamstrings tendon

The hamstring muscles are a collection of three distinct muscles on the back of the thigh. They are responsible for bending your knee and straightening the hip. The proximal hamstring tendons (the tendons closest to the middle of the body) attach to your sit bone (the ischium) and can often become afflicted with tendinopathy.

Upper hamstring tendon issues typically present with an aching pain just beneath your sit bone (right underneath the crease of your butt cheek) and will often feel worse after activities such as running or sprinting, jumping, and can be one of the many reasons why one hamstring feels tighter than the other during or after a workout.

Thankfully, bringing the strength of these commonly affected hip muscles up to optimal levels is rather straightforward.

Fixing tendinopathy in the hip

Dealing with tendinopathy in the hip usually takes a bit of work, but so long as you’re persistent and committed to resolving the issue, the outcomes are usually favorable.

Improving tendon health ultimately comes down to appropriately loading the tendon to provide the mechanical signaling required for restoring health to the unhealthy collagen fibers within the tendon.

Tendons don’t get better with rest; if they’re inflamed (tendonitis), reducing inflammation through inflammatory measures (reducing or modifying activities, NSAID medications, etc.) is a necessary preliminary step, but once excessive inflammation is reduced, loading the tendons against appropriate resistance is necessary.

The hardcore details are outside the scope of this article, but here’s what you need to know:

- Therapeutic exercise that challenges the tendon in a non-painful manner to provide an adequate stimulus to the tendon is your best bet.

- Any therapeutic exercise should be performed very slowly (each repetition should take anywhere from 10-15 seconds to complete). This helps eliminate stress-shielding from the healthy tendon fibers.

- Tendon loading exercises are allowed to produce discomfort – but not pain – so long as the discomfort is mild and does not worsen during the exercise.

- Read and follow along on this article that shows you the most effective glute medius strengthening exercise you can do. This one has been an absolute game-changer for a high percentage of my patients dealing with hip tendinosis.

Issue 2: Trochanteric bursitis

The trochanteric bursa is a large water ballon-like disc that sits on top of the greater trochanter, which is the bumpy knob you feel on the outside of your hip.

The function of this bursa (along with the over 200+ bursas elsewhere in the body) is to reduce the friction that otherwise would occur when various tissues, such as tendons, slide over them. More specifically, the trochanteric bursa works primarily to reduce the friction of bone as the gluteus maximus tendon slides over the top of it.

It’s not uncommon for bursas (the greater trochanteric bursa, in particular) to become irritated and inflamed. It is reported to affect approximately 8% of men and 15% of women and becomes much more common in active individuals, such as runners and other athletes.4

When the trochanteric bursa is inflamed, it will often produce pain when:

- Directly touched (known as being palpated).

- When the tissue over the top is stretched (such as when pulling the leg across the midline of the body), which places downward pressure on the bursa.

- Lifting the leg out to the side (abduction).

Getting rid of trochanteric bursitis

Bursitis can often be a bit of a tricky issue to deal with, but it often has favorable results with conservative treatment interventions. It is reported that up to 90% of all cases resolve with conservative treatment measures.5

Conservative interventions for treating trochanteric bursitis include5:

- Activity & lifestyle modification

- Physical therapy intervention (which can include manual therapy, shockwave therapy, etc.)

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs)

- Corticosteroid injections into the bursa

Unlike tendinopathy, dealing with bursitis is not so much about strengthening tissue since bursitis is an inflammatory condition, whereas tendinopathy is more about a lack of inflammation.

Your primary step for dealing with bursitis should be identifying and avoiding (or modifying) activities that worsen your pain (i.e., those that irritate the bursa). So, lifestyle modification will be an essential component for the time being (but not forever).

If your bursa is highly inflamed, remains stubborn, and doesn’t play by the rules, it may require lining up a steroid injection to get the inflammation under control. This is a relatively simple and straightforward procedure (and often necessary). Still, I always advocate that my patients try their best initially to modify their lifestyle to see if they can avoid any injections.

Lifestyle modifications for an inflamed trochanteric bursa can take a few weeks before results become noticeable, so stick with it, and if possible, get a qualified healthcare professional to help you with additional interventions and strategies along the way.

Issue 3: Labral pathology

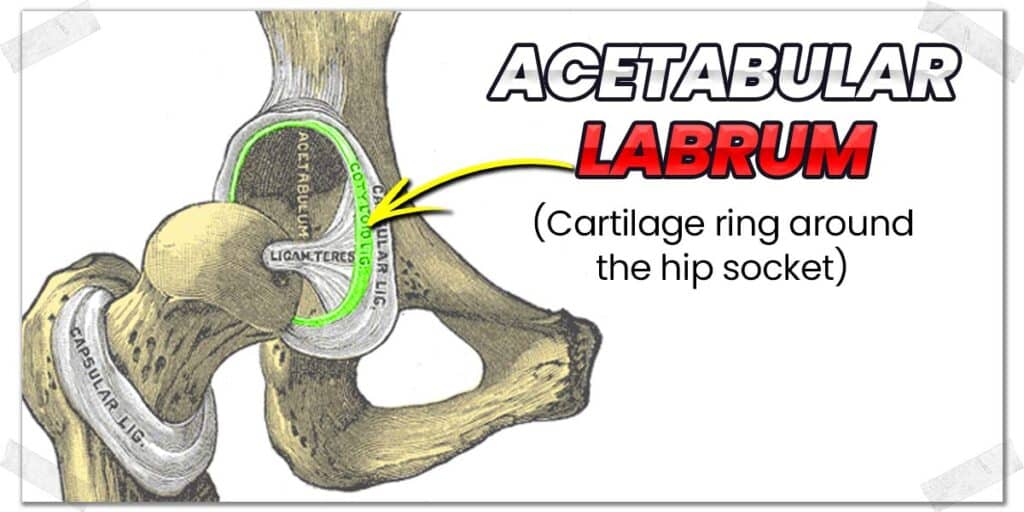

The labrum of the hip is a cartilage ring that wraps around the rim of the hip socket and acts to:6

- Help deepen the articulation of the ball and socket joint

- Provide shock absorption to the joint

- Lubricate the joint

- Help distribute pressure evenly around the joint

It’s not uncommon for this tough piece of fibrocartilage to get a bit chewed up or torn as we go through life, which can lead to hip symptoms such as pain and aching.

That being said, approximately 40% of all individuals with a labral tear are asymptomatic, meaning they don’t feel any pain or have any other symptoms arising from the tear, so just because you have a tear (if it’s confirmed you have one), it by no means guarantees this to be the cause of your pain.7

Generally speaking, a torn labrum will not tolerate going into a flexed and internally rotated hip position (known as the flexion internal rotation test), as this position essentially pinches or compresses the labrum.

Common symptoms of labral pathology include6:

- Anterior inguinal pain (the most common symptom)

- Lateral thigh pain (less prevalent)

- Buttock pain (less prevalent)

It’s important to realize that while these symptoms are described as “pain,” many individuals often interpret aching in the hip as a form of hip pain.

Dealing with (and fixing) labral issues

Since the labrum is a piece of fibrocartilage, it doesn’t have an adequate blood supply, making physical repair via the body’s own means quite unlikely.6 (Technically speaking, it has its blood supply from the obturator artery along with the superior and inferior gluteal arteries, however, the extent of blood supply into the labrum is somewhat controversial.)

This can sound quite frustrating for those hoping to hear the labrum can repair itself on its own, but there’s still good news here.

Related article: Injuries & Reclaiming Exercise Motivation (Practical Steps)

Thankfully there are some very helpful conservative interventions you can implement if you’re experiencing symptoms arising from a torn labrum. Avoiding pain-provoking positions (typically flexion with internal rotation) is an easy starting point. Additionally, hip strengthening exercises can also be notably helpful.

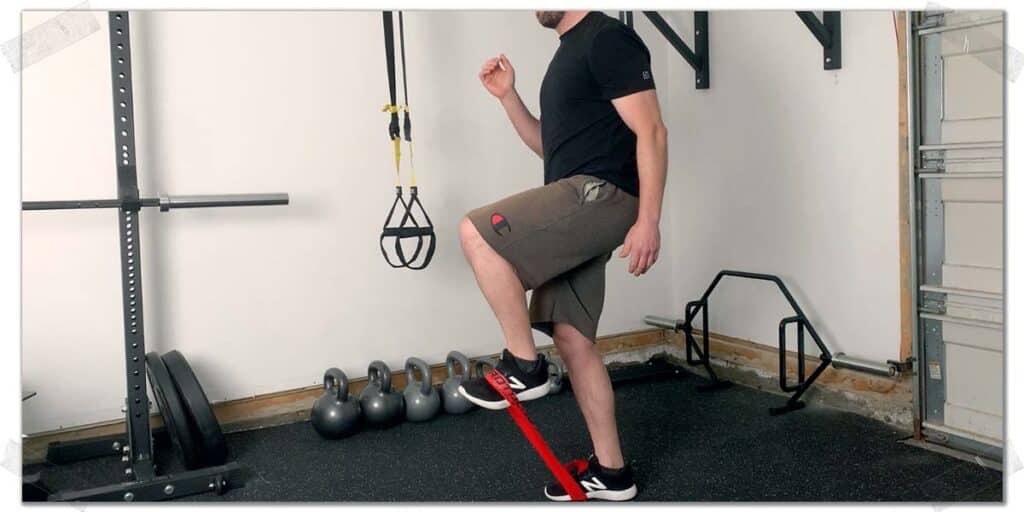

From a conservative standpoint, your best bet for offsetting any labral issues will be to perform deep gluteal strengthening exercises, which can help control your hip movement. The more stability and strength your hip muscles have, the less likely you will be to irritate the labrum from inadequate hip control.

Some rudimentary hip strengthening exercises can include:

- Clamshells

- Side lying leg lifts (hip abductions)

- Standing hip abductions

(A quick Google search of any of these exercises will point you in the right direction for how to perform them)

Again, don’t go making the assumption here that your hip labrum is torn just because I’m mentioning it within this article; a qualified healthcare specialist will need to do an evaluation and refer you for medical imaging to confirm the presence or absence of a labral issue.

Issue 4: Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)

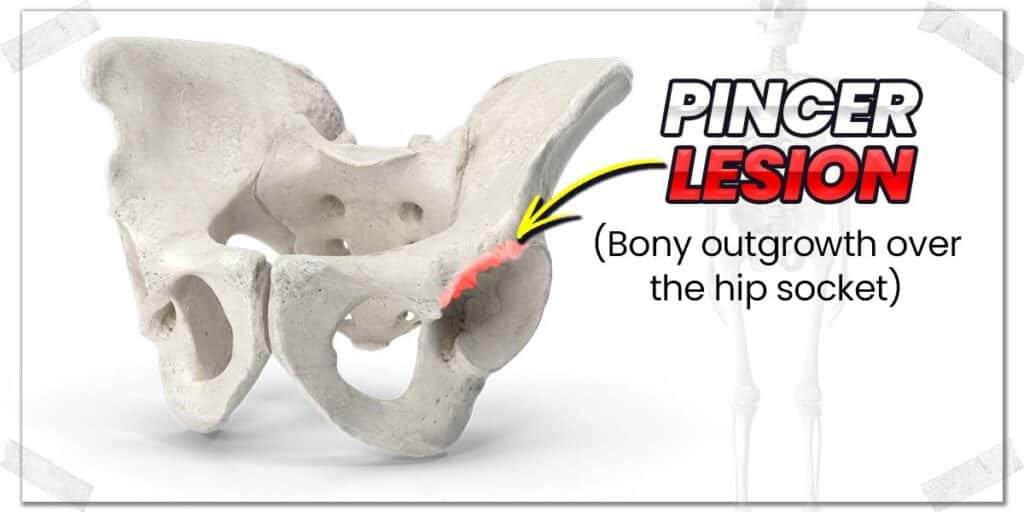

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a hip condition involving premature contact between the thigh bone (femur) and the brim of the hip socket (the acetabulum) when moving the hip.

This abnormal contact occurs with specific hip movements, such as when flexing (bending) the hip. The cause of this abnormal pinching is the result of bony overgrowth on either the neck of the femur, the rim of the acetabulum or both.

- A cam lesion refers to the bony growth occurring on the neck of the femur.

- A pincer lesion refers to the bony overgrowth occurring on the acetabular rim.

The underlying cause for FAI is believed to be multifactorial, so it’s highly unlikely that it’s one individual issue or event that led to the development of any FAI you might have.8

To determine if you have FAI, your doctor will need to order X-ray imaging of your hip, which will thereafter be easy to rule in or out the presence of any bony overgrowth on either the neck of the femur (thigh bone) or on the brim of the acetabulum (hip socket).

Dealing with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)

Just as with labral issues, conservative measures involving strengthening the deep hip stabilizers and the core muscles have been found to be helpful for improving symptoms in those with FAI.9,10 Additionally, avoiding the same pain-provoking positions as with labral tears is also a smart move to make.

Pro tip: FAI can cause or lead to the worsening of any labral issues within the hip since the body overgrowth(s) tend to pinch or put pressure on the labrum, further irritating or worsening the labrum.

Arthroscopic surgical procedures can be performed to resurface any bony surfaces (removing the bony overgrowth); however, long-term outcomes don’t appear to be statistically any more favorable than conservative measures.

As always, start with conservative measures (strengthening your hip muscles and activity modifications) and be diligent for a few months to see if you can get your aching or pain resolved before opting for surgical intervention.

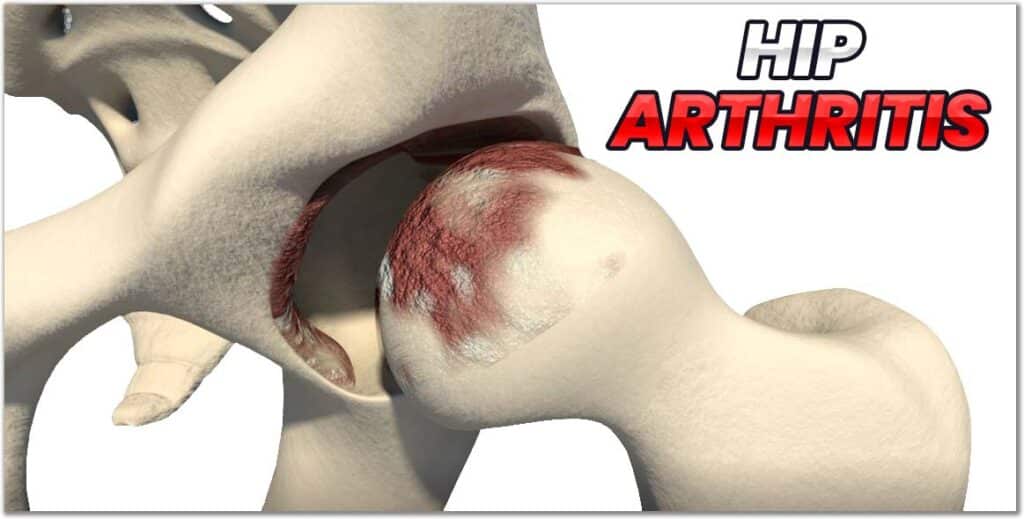

Issue 5: Arthritis of the hip joint

Arthritis of this hip is a common culprit for hip pain, and it can often be noticeably more uncomfortable after a workout or physical activity session. To be clear here, we’re specifically talking about osteoarthritis (OA), referring to the breakdown and degeneration of cartilage covering the head of the femur (the ball) and the acetabulum (the socket) of this hip joint.

It’s currently believed that osteoarthritis of the hip isn’t the result of one individual issue but rather from various conditions that share a common pathway to the resulting degeneration of the joint.11

The most common symptoms with hip OA tend to be pain, aching, and stiffness within the joint, often within the groin area. It tends to be notably worse after waking in the morning or after undergoing extended rest periods (not moving).

While hip arthritis can affect a wide population, it most notably affects11:

- Individuals in the fifth and sixth decade of life, with prevalence increasing each decade afterwards (it tends to affect men and women somewhat equally).

- Individuals who are obese (due to the increased weight-bearing of the ball and socket joint).

- Those who are genetically predisposed to the onset of hip arthritis.

- Working-class individuals who have occupations involving heavy manual work or those who participate in high-impact activities or sports.

Dealing with osteoarthritis of the hip joint

When it comes to tackling osteoarthritis, the name of the game is to find ways to keep the joint moving without further irritating it in the process.

Keeping an arthritic hip still is a recipe for disaster, as the cartilage in synovial joints (the hip being one such joint) receives its oxygen, nutrients and other healthy substances contained within the fluid.

As such, movement pushes the synovial fluid around the joint, ensuring the hip cartilage has access to the substances it needs to maintain its health. So the key is to move the joint as a means to continually bathe the hip cartilage in synovial fluid with pain-free movement.

If you’ve been diagnosed with an arthritic hip and it’s mild, you may want to ensure that you avoid any high-impact activities and replace them with less impact-based activities. Examples of what this can look like include:

- Opting to use the elliptical machine instead of jogging on the treadmill.

- Performing cardio sessions on a stationary bike.

- Avoiding lower-body plyometric exercises and opting for slow, tempo-based loading instead.

Regarding that last point, slow, tempo-based exercises will allow you to strengthen and challenge your leg and hip muscles without needing to load them with excessively heavy weight.

Utilizing blood flow restriction therapy can often be a highly effective intervention for ensuring adequate muscle stimulation and growth while keeping resistance exercises relatively light. Click the article link above if you want to learn why the science behind this is so promising, click/tap the red link above to learn more.

Pro tip: Blood flow restriction therapy has been shown in numerous scientific studies to improve lower body strength in individuals with arthritis who otherwise experience too much joint pain when strength training using traditional interventions.12–15

Issue 6: Referred pain from the lower back

Believe it or not, aching or generalized dysfunction within the hip can be the result of a lower back issue. In other words: the hip can merely be the victim while the lower back is the true culprit.

The function of the hip is largely intertwined with the function of the lower back and vice versa. When the lower back can’t move and operate as it otherwise should, the function of the hip must often compensate, which can create a whole new world of problems in the hip if left untreated for a prolonged time.

Compensatory issues that can affect the hip include:

- Overactive hip muscles, such as the glute medius, glute minimus, and tensor fasciae latae.

- Impaired mobility of the ball and socket joint.

The specifics of what might be going on with your lower back are something that I obviously have no information on, so your best bet here is to find a qualified orthopedic specialist who can evaluate your back and hip to ensure that your hip pain is or isn’t coming from your lower back.

However, I can provide a few general circumstances in which a lower back issue might cause pain in your hip. These circumstances include:

- Irritation of your lumbar facet joints, which can refer to an aching pain in your upper gluteal region (the upper back side of your hip).16

- A history of lower back pain or dysfunction involving impaired or limited overall mobility.

- A history of intervertebral disc issues (bulges, herniations, etc.) that can cause issues affecting the spinal nerve roots (a condition known as radiculopathy). These nerves travel from the lower back down into and through the hip. Irritated or sensitive nerves can

If you suspect that your lower back is the culprit of your hip pain or have a history of lower back issues, your best bet is to get an examination from a qualified healthcare professional who can do a deep dive into the underlying cause.

Pro tip: Even if your lower back is perfectly healthy, it’s worth having a dedicated spinal hygiene program consisting of gentle stretching and strengthening exercises to ensure it stays as healthy as possible!

Final Thoughts

Hips can ache for numerous reasons, either during or after physical activities. Usually, if there’s no pain involved, some activity modification and some rehabilitative exercises might be all that it takes to correct the issue or prevent it from becoming worse.

As with any other persistent issue causing physical discomfort or pain, it’s best to get an assessment from a qualified healthcare professional to determine the root cause of the issue. From there, attack the issue with consistency so that you can get back to your regular workouts without your hips hurting in the process.

Frequently asked questions

In addition to the information provided above, I’ve included a few answers to some commonly asked questions that patients and athletes often ask me when being evaluated and treated within the clinic. I hope these answers help provide a bit more insight for you!

References:

11. Lespasio MJ, Sultan AA, Piuzzi NS, et al. Hip osteoarthritis: a primer. Perm J. 2018;22.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!