Squatting is a fundamental movement pattern for humans. And whether you’re squatting with a barbell that holds hundreds of pounds across your back or only with mere bodyweight, this movement should never cause pain in your heel. Heel pain can be debilitating and spiral out of control if you’re not careful. Thankfully, I’ve written a detailed article here to help you get things sorted out.

But before diving into the details, here’s the two-sentence rundown on why you likely have pain in your heel when squatting and the first initial step to take for crushing this issue altogether:

Heel pain when squatting can result from biomechanical issues of the foot and ankle and can be associated with poor health of the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, retrocalcaneal bursa, or other similar tissues. Identifying and treating the underlying cause can get you back to pain-free squats.

Now, that’s the overly-simplified two-sentence answer, and to be clear, heel pain can be a tricky situation to deal with at times, but that’s why I’ve written this article!

So, if you want all the juicy details and secret sauce for why these issues arise and what it will take to overcome any of these common issues, then you’ll need to keep on reading (it will be worth it, trust me)!

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

Common issues: Causes of heel pain when squatting

As we get going with the article, please keep in mind that I can’t cover every possible source of heel pain within a single post (I wish I could, though!) Still, I’m able to cover the most prominent issues—the ones that affect the vast majority of the population, which just might be you. As we tend to say around our clinic, “common things are…common.”

Also, please remember, there’s no rule in life stating you can only have one single issue generating your pain; there are oftentimes two or more underlying issues playing off one another that can create various types of heel pain or discomfort (such as having plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinopathy, as an example). Still, for the sake of clarity within this article, I will be discussing each issue as a standalone problem.

What follows below are the more common sources of heel pain I see and treat within the clinic. I deal with these various heel issues all the time with the patients whom I treat and train. Generally speaking, each of these conditions responds well to conservative treatment (i.e., non-surgical intervention), so make a solid effort with your conservative rehabilitation before considering anything more drastic.

For any of the painful heel conditions discussed within this article, the length of recovery for treating any of them will depend on numerous factors, such as:

- The extent or severity of the issue

- Whether the issue is acute (newly acquired) or chronic (has been present for a longer time)

- The overall health of the individual

- The activity level of the individual

- The extent to which they adhere to their recovery guidelines

“When it comes to solutions that can help your heel feel better when squatting and throughout the rest of your day, it’s worth knowing that there are usually a handful of conservative interventions to try. Many of them can be implemented alongside one another, meaning you’re not confined to picking only one single intervention.”

Alright, let’s talk about what could be going on with your painful heel when you’re banging out your squats and how to get rid of it.

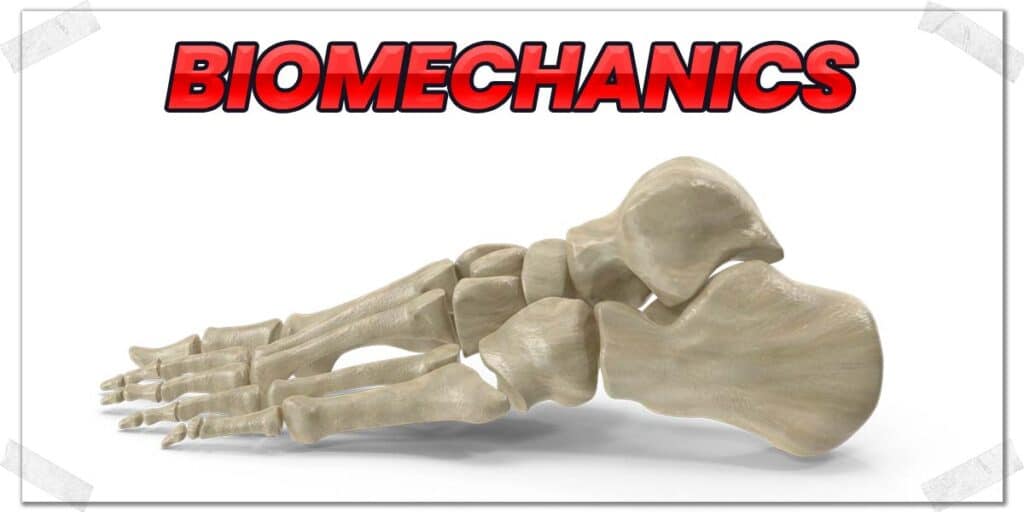

Issue 1: Biomechanical issues of the foot and ankle

The biomechanics of the foot and ankle are quite complex. There are thirty-three joints and twenty-six bones that articulate and move in a manner that allow us to perform activities such as squatting. And that’s not even mentioning the muscles, tendons and ligaments.

Everything is designed to work in unison to produce efficient, proper, and pain-free movement. It’s kind of like the alignment of your vehicle’s tires—if the steering is slightly off, it can lead to a host of other detrimental issues to the vehicle’s performance as time goes on.

Related article: When You Should And Shouldn’t Squat Barefoot (And Why It Matters)

While the specifics are far beyond the scope of this article, issues involving the positioning and function of the bones and joints within the foot and ankle can lead to pain in the heel when performing squats. Issues such as pes planus (being flat-footed), forefoot pronation (a forefoot that rolls inwards), subtalar eversion (a heel bone that isn’t ideally aligned), and other similar issues can lead to pain within the heel.

There are some simple strategies and corrections that can be implemented to help clean up some of these issues. To learn more about them, check out the “potential solutions section later in this article.

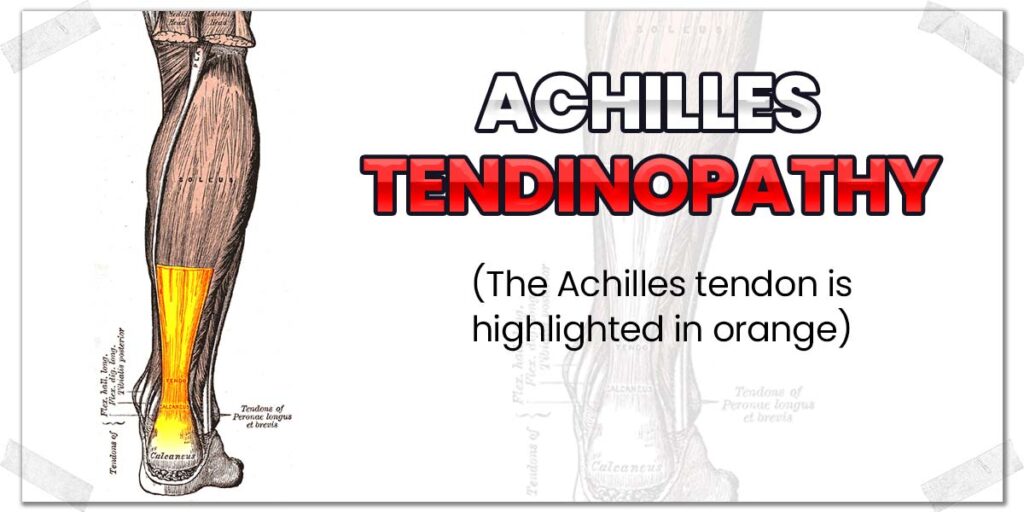

Issue 2: Achilles tendinopathy

The Achilles tendon is the thick, cord-like structure that runs down the back of your lower leg beneath your calf muscles. It attaches at the base of your heel bone, with its function being to transmit forces produced by your calf muscles, causing you to be able to pull your ankle downwards (called plantarflexion) as if pressing your foot down on a gas pedal.

Like any other tendon in the body, this tendon is prone to becoming sore, painful, or otherwise unhealthy. It’s one of the most commonly affected tendons in the body and, when unhealthy, can produce pain anywhere along the tendon. It’s most often felt around or just above the heel bone itself.

When a tendon is unhealthy, it’s known as being tendinopathic. In this case, most people with an unhealthy Achilles tendon have what’s known as tendinosis. It’s very similar to Tendonitis, and for simplicity’s sake, within this article, you can think of them as the same condition (though they’re technically different).

Tendons can become unhealthy, sore, and painful for various reasons. Typically, it will come down to one of two factors:

- Too little use of the tendon

- Too much use of the tendon

In either case, it needs to be stimulated back to health; prolonged rest likely won’t take care of the issue.

To read up on the latest scientific findings on how to deal with tendinosis, check out this outstanding journal article (link takes you to a PDF): Tendinopathy (Millar et. al, 2021)

Issue 3: Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis is a common (and often painful) condition affecting a thick tissue on the bottom of the foot known as the plantar fascia (I treat it all the time in the clinic). This thick, gristly tissue is similar to tendon tissue in that it doesn’t have a great blood supply and can be stubborn to heal if left to rest alone.

Anatomy fact: The plantar fascia plays a critical role in helping to provide the foot with its innate structure, including arch support.

The plantar fascia runs along the majority of the bottom of the foot, and while plantar fasciitis can arise in any subsequent area, symptoms such as pain most often arise towards the heel. It often feels the worst in the morning when taking the first few steps after getting out of bed.

Related content:

It can often feel notably worse when performing exercises such as squats or lunges since these movements require the plantar fascia to endure greater stress and stretch when lowering the body toward the floor. As such, it’s not uncommon for my patients to tell me that squatting makes their plantar fascia pain worse.

Pro tip: The term plantar “fasciitis” is falling out of favour with the scientific community since this term implies there is an inflammatory process taking place within the plantar fascia, which we now realize isn’t necessarily the case. As such, you may hear people also refer to this condition as plantar fasciopathy since this term implies a pathological issue (i.e. something is wrong) without inflammation being present.

Thankfully, this painful and very annoying foot issue typically has good outcomes when treated with conservative measures. I’ll elaborate on them in the “solutions” section of the article. However, here are a couple of outstanding scientific articles to read regarding the treatment and prognosis (the expected outcome) of plantar fasciitis.

Plantar fasciitis article 1: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on the Epidemiology, Evaluation, and Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis article 2: Plantar fasciitis in athletes: diagnostic and treatment strategies. A systematic review

Issue 4: Retrocalcaneal bursitis

The human body is filled with over two-hundred bursa pads, which are little water balloon-like structures that help to reduce friction (and subsequent irritation) that would otherwise arise between different tissues in the body that frequently rub over one another.

Unfortunately, these bursa pads are prone to becoming irritated and inflamed, leading to a condition known as bursitis.

One such bursa is the retrocalcaneal (“behind the calcaneus bone”) bursa (the calcaneus is the anatomical name for the heel bone). While this bursa can become irritated for different reasons, the end result is typically the same: pain that’s felt along the back of the heel from retrocalcaneal bursitis.

Bursitis can be tricky to deal with, but if you’re patient and make appropriate changes to your footwear and activity levels, you can likely get it under control without further intervention (such as a cortisone shot). Check out the solutions section further down in this article for more specifics.

Issue 5: Heel fat pad syndrome

The bottom of your heel contains a thick layer of fatty tissue known as a fat pad. Heel fat pad syndrome of the heel refers to pain arising on the bottom of the heel from an issue with this structure. It can arise for many reasons and often feels like a deep bruising discomfort that is felt when placed under pressure (such as when walking, running, and squatting).

It can be a tricky issue to treat, though there are a number of conservative interventions that can help to reduce any discomfort and help you concours the situation.

To learn more about this issue, you can check out this article on physio-pedia: Heel fat pad syndrome.

You can also read the solutions section within this article for conservative measures for offloading your fat pad when squatting or performing other daily activities.

Issue 6: Haglund’s deformity

Haglund’s deformity (also known as Haglund’s syndrome) is a condition that can cause pain in the back of the heel. It results from extra bone growth occurring on top of the back of the calcaneus (heel) bone. Sometimes it’s not painful, while at other times or for certain individuals, it can be very painful.

It’s not entirely understood why this condition arises; however, it seems to be correlated with Achilles tendon issues, foot biomechanics (such as high arches), and wearing footwear with stiff or ridged backing (such as ski boots).

Haglund’s deformity is often easy to spot since it involves a large protuberance or bump that builds up on the backside of the heel bone (the calcaneus).

Pro tip: Haglund’s deformity can also be present with additional conditions such as Achilles tendon issues (such as tendinitis or tendinosis) or retrocalcaneal bursitis.

If you have this issue, you can typically take care of any pain or discomfort through conservative measures (discussed in the solutions section below), though you won’t be able to get rid of the bump that has built up on your heel, so just consider it a souvenir from the days you were experiencing heel pain when squatting and didn’t know what to do about it until reading this article.

Issue 7: Heel spurs

A heel spur is a bony projection that grows on the calcaneus (heel) bone. They can grow either on the bottom side of the heel or on the backside, where the Achilles tendon attaches to the bottom of the calcaneus. There are numerous reasons or causes for why these spurs can form. Spurs that develop on the bottom of the calcaneus are often due to plantar fasciitis, while spurs that develop on the back of the calcaneus can be associated with Achilles tendon issues, such as tendinopathy.

Heel spurs are best detected through a simple X-ray of the foot, and it’s important to note that not all heel spurs are painful. As such, if you do have an X-ray revealing the presence of a heel spur, you will need to work with a qualified healthcare professional (such as an orthopedic specialist) to determine what may be the underlying cause of your pain (plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, etc.).

Conservative interventions that can help reduce heel spur pain include footwear modification, heel cups, orthotics, and soft tissue treatment for the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia.

Read through the solutions section of this article for more insight into these interventions.

Potential solutions: Time to heal your heel

When it comes to finding and implementing solutions that can help your heel feel better when squatting and throughout the rest of your day, it’s worth knowing that there are usually a handful of helpful adjuncts to try. Many of them can be implemented alongside one another, meaning you’re not confined to picking only one single intervention.

The solutions below are the more common approaches I’ll take with my patients and athletes when helping them stay as active as possible to control their heel pain as I help treat them with other conservative measures.

“Finding ways to modify your activities (inside and outside of the gym) can help to ensure your heel pain or the underlying issue causing the pain doesn’t worsen. It won’t likely be a cure, but it will help ensure things don’t get worse.”

Solution 1: Activity modification

It’s not a sexy-sounding solution, but it is one that is likely required for the time being. Finding ways to modify your activities (inside and outside of the gym) can help to ensure your heel pain or the underlying issue causing the pain doesn’t worsen. It won’t likely be a cure, but it will help ensure things don’t get worse.

Keep in mind that modifying your activities doesn’t mean you need to (or should) stop being physically active altogether. Many times you can perform leg-strengthening exercises similar to squats without incurring heel pain along the way.

Open chain exercises (exercises where the feet aren’t in contact with the floor) are examples of how one can avoid irritating their heel or worsening their pain while still strengthening their legs.

Exercises such as leg extensions and seated or prone hamstring curls are examples of lower-body strengthening exercises that can be performed without putting any weight on the bottom of your heel.

The ways and extent to which you modify or change up your workouts or activities outside of the gym will obviously vary, so take the time required to find out:

- Which activities you may need to temporarily forego altogether

- Which activates you may need to scale back (either for frequency or intensity)

- Which new activities or exercises (that don’t cause pain) you may want to consider implementing

Pushing through your heel pain and hoping for the best isn’t an optimal training strategy, so have the diligence to modify your activities and exercises for the time being as you work to get your heel pain under control.

If you want to keep squatting, know that none of this necessarily means you need to forego your squatting altogether. It may simply mean that you need to modify other activities (jogging, plyometric exercises, playing sports, etc.) that may either be the sole cause of your heel pain which accentuates your heel pain when you squat.

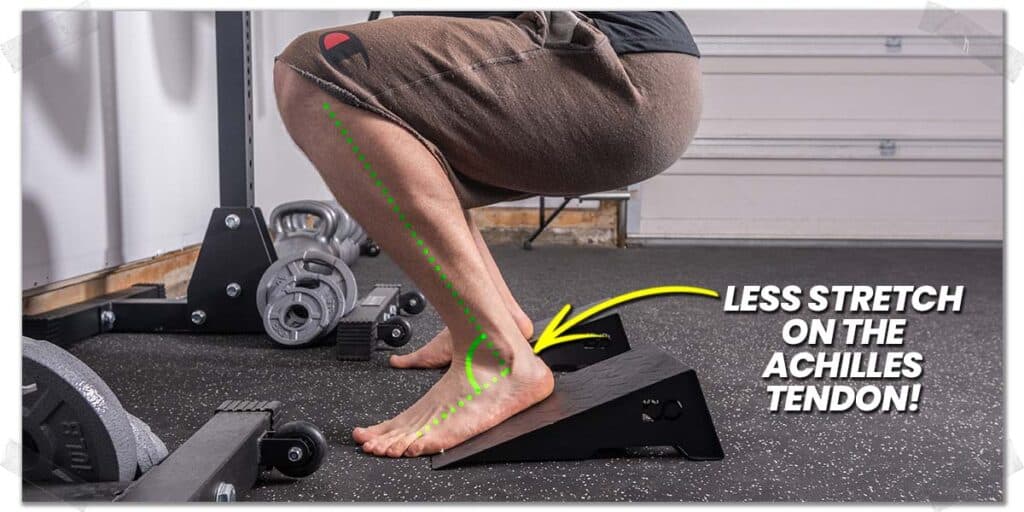

Solution 2: Squat wedges

Squat wedges (often called heel wedges) are a perfect solution for those who have certain types of heel pain when squatting, notably those with Achilles tendon issues and who want to find ways to continue to squat.

Wedges work by decreasing the range of motion the ankle joint must undergo during a traditional squat. As a result, they decrease the stretch that the Achilles tendon undergoes, which can notably reduce—or even eliminate—pain from an unhealthy Achilles tendon or tight calf muscles.

Pro tip: Heel wedges can also be used to challenge the leg muscles in a different manner when squatting; they don’t have to be used exclusively for alleviating heel pain.

I’ve written an extensive article on how, why, and when to use these wedges, so if you want all the juicy details, check out my article: Squat Wedges: Benefits | Drawbacks | When To Use Them

Solution 3: Footwear modification, heel cups, and orthotics

Squat wedges (solution 1) work as an outstanding adjunct when you’re in the gym, and you’re squatting, but they can’t offer much help for the rest of your daily activities. Thankfully, footwear modifications such as heel cups, orthotics, using Moleskin, and other similar adjuncts can help quite nicely. A quick overview of each is listed below.

Modifying your footwear can be one of the ways you can help to reduce or eliminate any heel pain you’re noticing. While this can take many forms, these modifications can lead to improved foot and ankle mechanics, less direct impact on your heel, or even modified ranges of motion that help to reduce stretch or pressure on the Achilles tendon.

Simple footwear modifications can include:

- Switching from shoes with hard or minimal insoles to those with a more cushioned or padded structure.

- Switching to shoes that have an elevated heel or more of a built-in “rocker,” such as Hoka shoes, to help reduce the amount of stretch the bottom of the foot or the back of the heel must undergo when walking.

- Switching to shoes with softer or more padded heel support to help reduce any direct pressure being placed on the back of the heel.

Heel cups (also called heel inserts or heel cushions) are a commonly employed conservative intervention for those experiencing pain on the bottom or back of their heel. They work through two primary mechanisms:

- Provide direct cushioning to the bottom of the heel.

- Slightly elevate the heel when standing, which can decrease the stretch, tension or soreness that may be felt along the Achilles tendon towards the base of the heel.

They can be purchased at most local drug stores and even in the pharmacy section of many grocery stores. They can be made from various materials, often made from a silicone gel, providing soft cushioning to the heel. As such, they can be a great first-line treatment adjunct for heel spurs and plantar fasciitis.

Orthotics are commonly used to treat multiple foot, heel, and ankle issues. Ultimately, they work by correcting the biomechanics of the foot and ankle (which can impact the position and function of the calcaneus (heel). Orthotics can either be purchased over the counter (at drug stores, for example) or be made custom to the needs of your feet through a qualified specialist such as a pedorthist, podiatrist, or other qualified professional.

While custom-made orthotics aren’t cheap, depending on your needs, they can be a worthy investment for those struggling with biomechanical issues in their feet and ankles, leading to persistent pain that hasn’t resolved through other conservative treatment measures.

Solution 4: Taping techniques

Taping techniques can be surprisingly helpful when dealing with heel pain, be it when squatting or when going through the rest of your daily activities. In particular, there are two techniques I often use for my athletes and patients experiencing heel pain, either of which will depend on the cause of their heel pain, which is discussed below.

Technique 1: Low dye taping

The Low Dye technique is a classic structural-based taping technique that can make notable differences in reducing foot and heel pain. Anecdotally, many of my patients mention that it makes a substantial difference when it comes to reducing their heel pain, and the technique itself has some scientific evidence to back it up.

This technique works best for conditions such as plantar fasciitis, particularly when pain is being felt on the bottom of the heel, though there are other conditions for which it can also be helpful.

To learn how to perform this technique, you can check out my YouTube video below:

Technique 2: Kinesio taping for the Achilles’ tendon

Kinesio taping (often called K-taping) can be a surprisingly helpful way to knock down heel pain arising from an irritated or unhealthy Achilles tendon. It’s not a cure by any means, but it can help to turn down nociception (the awareness of pain) due to the tape’s sensory stimulus arising on the skin (known as the gate theory of pain control).

Related article: How To K-Tape Your Achilles Tendon All By Yourself: A Step-By-Step Guide

Additionally, the tape can theoretically help to improve fluid dynamics beneath the skin, which can help the healing process, though, to the best of my knowledge, this is more on the theoretical side.

Anecdotally, I can say that many of my patients feel a very noticeable benefit from this taping technique. It’s a simple process to perform, and anything that helps to take the edge off is something my patients appreciate.

If you want to learn more about how to perform this simple technique, you can check out my step-by-step article or follow along in my YouTube video, both of which are listed below:

Final thoughts

Experiencing heel pain during squats is a relatively common issue that many active individuals face. No one is immune to having this issue arise. Thankfully, conservative measures are often effective in treating and eliminating heel pain once the root source of the dysfunction has been identified. So, take the time required and get the help needed to figure out what’s going on so that you can get back to pain-free squatting!

Frequently Asked Questions

Since there can be numerous questions that arise when discussing squatting and heels, I’ve included a few brief answers below to commonly asked questions that my patients, athletes, and plenty of other folks on the internet have regarding these topics!

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!