Anyone who thinks that front squats only strengthens your legs has clearly never performed them with heavy weight before (can I get an amen?). And if you happen to find your upper back getting sore from some challenging front squats, fear not, as it’s quite often to be expected.

Upper back soreness from front squats is due to the intense demand the upper back muscles undergo to hold the torso upright during the movement. This is biomechanically due to the altered center of gravity that occurs with front squats. The heavier the weight, the harder these muscles must work.

Sometimes lifters and other active individuals wonder if they’re doing something wrong during the movement or if there’s something wrong with their upper back if it does get sore from front squats. There are a few things to unpack here, but generally speaking, mild muscle soreness in the upper back region is to be expected if you’re new to the exercise or have decided to recently up the weight you’re lifting.

So, keep on reading if you want all the details about why this happens, what it all means, and how to get rid of this issue!

Related Article: Nine Ways to Make Lunges WAY Harder Without Adding Any Weight

Disclaimer: While I am a physical therapist, I am not YOUR physical therapist. As a result, I cannot tell you whether or not front squats or any treatments for upper back soreness may or may not be appropriate for you. By following any information within this post and on this website, you are doing so at your own risk. You are advised to seek appropriate medical insight from a qualified healthcare professional for any pain you may be experiencing.

Basic upper back anatomy

Arguably the best place to start when it comes to unpacking the contents of this article is to first go over the basics of anatomy for the region that tends to get sore.

If you can better visualize and understand some of the structures at play when it comes to maintaining an upright posture when front squatting, the rest of the contents within this article will be way more straightforward to understand.

Specific muscles of the upper back

There are a lot of muscles that span across the upper back, both in the horizontal direction and the vertical direction. I won’t be going over all of them. Instead, I will focus on the ones that play a prominent role in preventing your spine from flexing (rounding) in the forward direction (think of the direction when bending over to touch your toes).

Anytime a force (such as a weighted barbell) wants to pull your upper body into this flexed position, the segmental stabilizers and the global stabilizer muscles of the back will contract in an attempt to pull the spine straight/backwards (known as extension).

Segmental (local) stabilizers are muscles that (in this case) run up along the spine and connect from one vertebra to the next (i.e. one segment to the next). These muscles produce some movement of the spine but tend to have an enhanced role in creating stability of the spine. Due to this nature, these muscles are deeper in the body, and thus, underneath the more superficial global stabilizer muscles. I tend to think of them like steel girders that reinforce tall buildings.

Segmental stabilizers include (but are not limited to):

- The iliocostalis

- The longissimus thoracis

- The multifidus

Global stabilizers, on the other hand, are the muscles that (in this case) span across the spine (vertebrae) rather than attaching to each and every segment. These are the more superficial muscles and tend to be the ones that are more popular or well known to gym-goers. Unlike their counterparts, these muscles don’t work to provide stability for the spine from one segment to the next as they do with stabilizing the spine as a whole. They also serve more of a primary role of producing movements in contrast to the segmental stabilizers.

Global stabilizers include (but are not limited to):

- The iliocostalis lumborum

- The lateral fibers of the quadratus lumborum

- The internal & external obliques

Fun fact: In the world of anatomy, a muscle is only considered a true “muscle of the back” if it is innervated by a nerve known as the dorsal primary rami. If a muscle on the back is not innervated by this nerve, it is TECHNICALLY not a true back muscle. Crazy, eh?

RELATED CONTENT:

The joints of the thoracic spine

The human spine is divided into three main sections:

- The cervical spine

- The thoracic spine

- The lumbar spine

The thoracic spine pertains to the upper back region that has been the focus of this article so far. Many of the segmental stabilizers of the spine attach to these bones.

The joints of the spine are known as the facet joints. The thoracic spine’s facet joints are sloped upwards, allowing the thoracic spine to produce a lot of flexion, rotation, and side bending movements. However, due to their upwards-sloping angle, they don’t allow for much extension (backwards bending).

When the facet joints act up

It is entirely possible for these joints to become irritated, stiff or even jammed up or stuck, which can produce discomfort or even pain (more on this later on). So, it’s possible that some of your soreness could be the result of cranky joints. But if you’re experiencing more of a broad and diffuse discomfort across your back, it’s not likely to be due to your joints; facet joint pain tends to be more focal and sharp in nature.

Basic biomechanics (like, very basic)

Now that you know your anatomy, it’s a good idea to go over the basics of how the front squat differs from the back squat and why it puts your mid and upper back muscles to work throughout the movement. Hopefully, having a better understanding of the forces at play will put your mind at ease regarding why you feel like your upper back gets lit up after these squats.

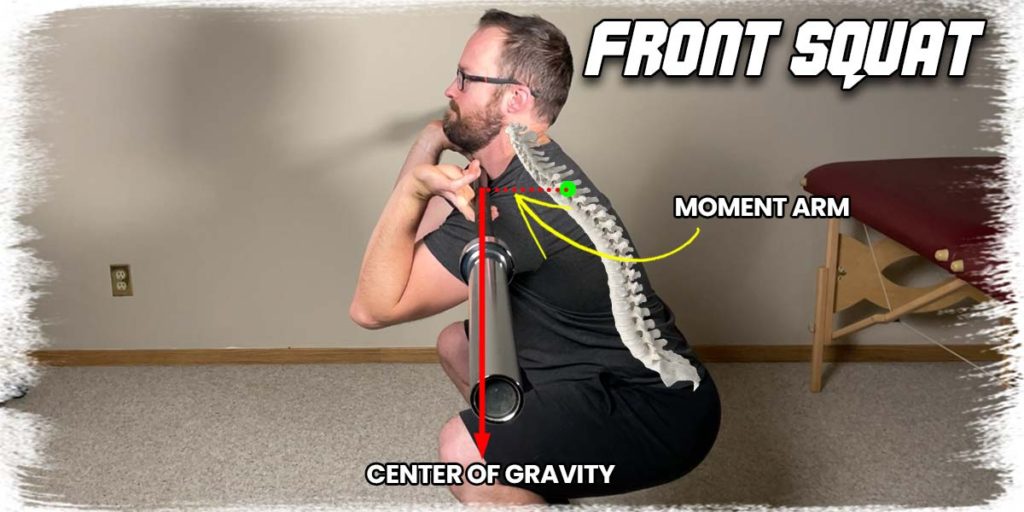

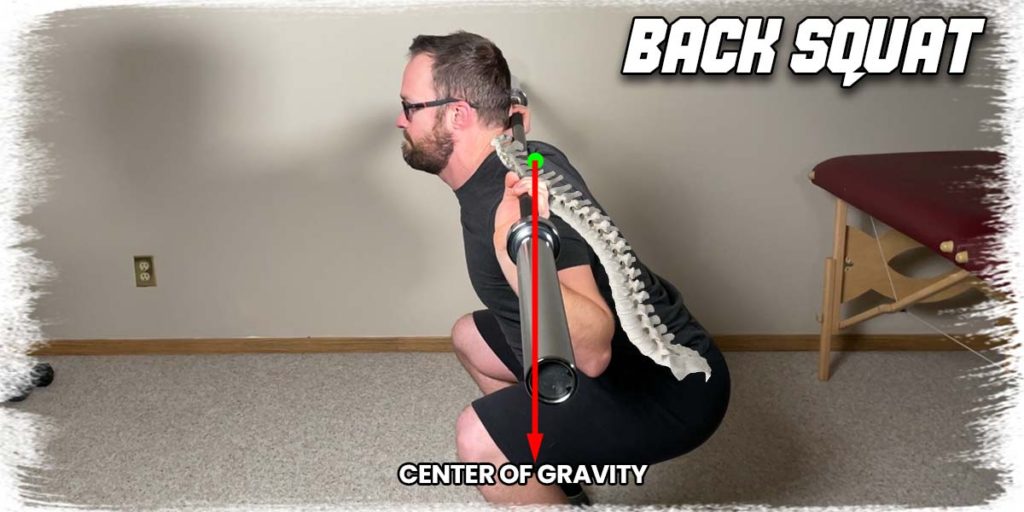

Biomechanics simply refers to mechanical forces and laws acting on different body parts or structures of the body. I’m going to keep it incredibly simple here as there’s no need to go highly in-depth with any of this; all we have to go over here is understanding the concept of center of gravity and how the front squat creates a moment arm in relation to the thoracic spine.

Notice how the weight of the barbell (and any weight on it) runs approximately directly through the thoracic spine with a traditional back squat. As a result, there is essentially no moment arm that exists. Therefore, the thoracic spine doesn’t have any force attempting to pull it into flexion.

Contrast this with the short moment arm that exists with the front squat. Since the weight is now approximately on top of the collar bone, there is some distance between the barbell and the thoracic spine. It’s a short moment arm, but due to the heavy weight, it still produces a higher amount of torque on this region of the spine, making the muscles work more aggressively to counteract the torque that would otherwise pull the spine into flexion.

Interpreting your discomfort

Different types of discomfort can be experienced in the upper back after a challenging front squat session, and it’s hard to effectively take care of the issue if you don’t know what the discomfort is likely from. The most common discomfort is likely to be sore, aching muscles, which I’ll elaborate on below. Still, I’ll thereafter quickly discuss one other type of discomfort that can arise as well.

Sore, achy muscles

This is the type of discomfort that is most often experienced after a challenging session of front squats. This type of discomfort is known as myalgic pain/discomfort. After a challenging front squat session, it’s typically felt symmetrically on the upper back (i.e. one side isn’t noticeably more sore than the other).

If your soreness feels like it’s made your upper back stiff or tight or that your soreness is a bit greater towards the center of your upper back rather than out to the sides, take note. It’s likely a solid indication that your muscles got taken for a ride during your front squats (not necessarily a bad thing) and are now in recovery mode after working excessively hard to keep your torso upright on each and every rep that you performed.

You may feel that the discomfort is more prominent when putting your upper back into specific positions (such as when fully rounding or straightening your thoracic spine or when bending sideways), which causes the stiff muscles to stretch out or contract, either of which can make the muscles more sensitive in the moment.

Generally speaking, if the sensations of soreness, tightness or achiness are less prominent when you’re at rest and more prominent when you’re producing physical movement (either contracting or stretching) of your upper back, it indicates that the soreness is likely coming from the muscles.1

Sharp, pinching sensations

Though typically not described as “sore” or “achy,” sometimes the facet joints of the thoracic spine can become irritated or stuck, which can certainly create discomfort in the affected area.

These types of joint-specific issues tend to be more focal and sharp in their pain presentation than diffuse and achy across a large area. Facet joints in the thoracic spine also have the ability to refer pain to the ribs and chest wall.2,3 Nonetheless, it’s still a less-than-optimal experience and one that leads to discomfort or even pain.

Positions that involve placing these joints at the limits of their ranges or into a position of maximal joint congruency (known as the closed-packed position) will often produce the sharper, more focal sensation of discomfort.

Effective solutions

Now that you’ve been briefed on the basic mechanisms that lead to upper back stiffness from front squats and what different types of discomfort can signify, we’d better go over some rudimentary approaches to getting things under control and ensuring this doesn’t happen again.

Solution 1: Strengthen your back

This is the long-term solution here, and while it, therefore, won’t be the quickest fix, it’s ultimately what you should be aiming for. Thankfully, this is relatively straightforward to rectify in an otherwise healthy individual.

Assuming your upper back soreness was indeed from your muscles working harder than they were used to when front squatting, the solution is to keep on performing front squats in your training regimen, but at a reduced load from what caused them to get sore.

Mind you, I’m assuming that the soreness you experienced was excessive and very uncomfortable; if your soreness was relatively minimal, you might just need another couple of sessions to get the upper back muscles accustomed to the demands of the exercise without even dropping the weight down.

You can also opt to incorporate other strength training exercises into your training regimen that target these same muscles and general muscles in the area.

Solution 2: Mobilize your joints

Regardless of whether or not any of your joints might be causing the specific discomfort incurred from your front squats, putting some gentle movement through your thoracic facet joints will be appreciated by your body.

Most individuals could benefit from keeping their thoracic spine moving more frequently, to begin with. On top of that, forcing your spine to move through motions it may otherwise struggle with can help ensure that things don’t get any worse.

Here are some of my favorite thoracic spine movements for these conditions:

Open books

This classic exercise works to mobilize your thoracic spine through proving rotation in this region.

- Lay on your side and pull your knees up towards your chest (this locks up your lumbar spine joints and forces more movement to occur specifically in the thoracic spine)

- With your arms straight in front of you and palms touching, keep your bottom arm on the ground and rotate backwards with your top arm (just like a book being opened). Go as far as is comfortable for you.

- Return to the starting position and repeat for desired repetitions.

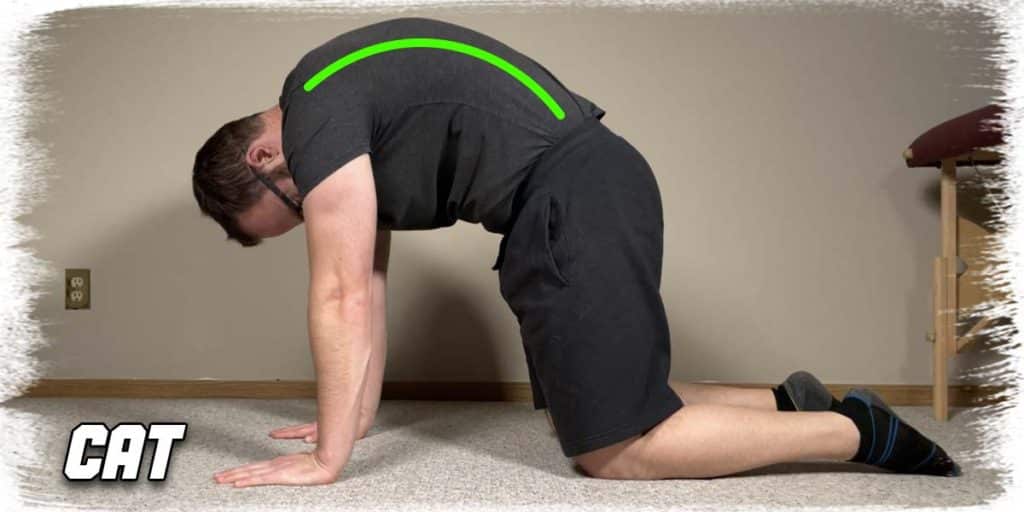

Cat/cows

A classic yoga-based movement right here that works to help mobilize the thoracic spine through flexion and extension.

- Assume the quadruped position on all fours with your limbs directly underneath you.

- Slowly drop your stomach down to the ground (the cow position), which will bring your spine into extension. Hold this position, then return to your starting, neutral-spine position.

- Next, push your spine as high upwards as possible (the cat position). Hold for a few seconds.

- Return to the starting position and repeat the entire process.

Note: if you experience a pinching or sharp sensation at the end range of either position, shorten your range of motion and perform as much of the movement as possible without entering into the range that produces the sharp discomfort.

Foam rolling with flexion & extension bias

The key with these rolling exercises is to roll over the shoulder-blade level of the thoracic spine while holding yourself in the correct position. In my experience, most often, people will benefit more from the flexion bias than the extension bias (for reasons beyond the scope of this article); however, both can be beneficial at times, so I’ll include both.

For the flexion bias:

- Lay on the foam roller across your shoulder blades.

- Bring your chin to your chest, and hold it there by interlocking your fingers behind your head.

- Lift your hips as high up into the air as possible while simultaneously attempting to curl your tailbone up between your legs. Hold this position.

- While holding the above position, slowly roll up and down on the roller from approximately the bottom to the top of your shoulder blades.

For the extension bias:

- Lay on the foam roller across your shoulder blades.

- Interlock your fingers behind your head (to support it) and then slowly push your chin up in the air as if trying to look behind you.

- Keep your hips on the ground and keep them there.

- Slowly roll up and down on the roller from approximately the bottom to the top of your shoulder blades.

Solution 3: Melt your muscles

In terms of getting muscles to settle down, a solid portion of that can be achieved through the movements mentioned in the section above; sore muscles appreciate low-intensity movement. And for any exercises where you’re moving your upper back to mobilize your joints, your muscles will be getting some movement as well. The cat/cow exercise is a great example of this.

Targeting the paraspinal muscles

This little technique I’m about to go over here can also double as a way to mobilize some of the joints of your thoracic spine, so this is an excellent little two-for-one deal, and it usually feels rather nice to perform.

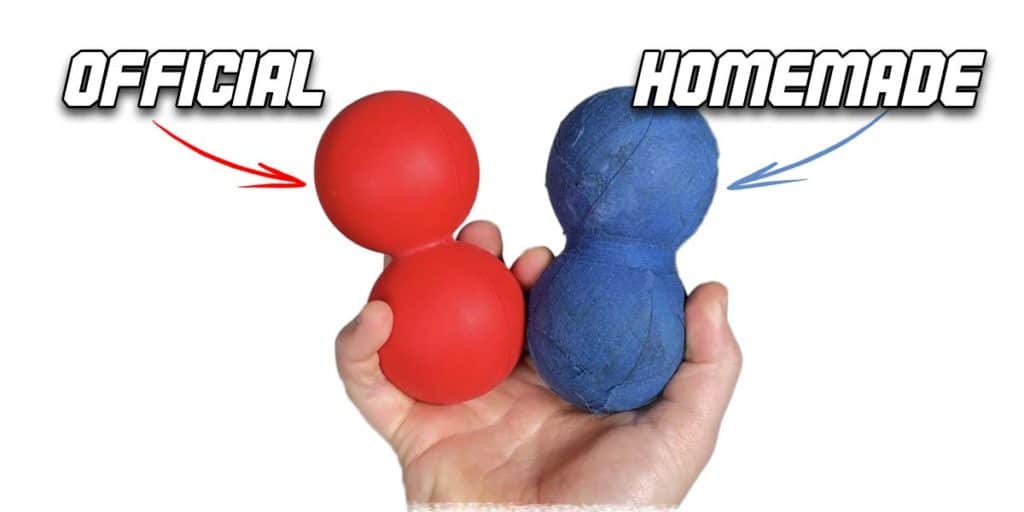

You’ll need to have a peanut roller on hand, or you can make one by taping two tennis balls together. It doesn’t have to be fancy; it just has to be enough to keep them held together in the shape of a peanut while you perform the technique.

Pro tip: if tennis balls aren’t firm enough for your needs, you can tape two lacrosse balls together, which will have substantially less give than tennis balls when laying on top of them.

From there, lay the peanut on the ground, and then lay your mid-upper back directly on top so that the spinous process (the knobby bone on the center of your spine) fits directly into the little groove of the peanut. Next, give yourself a big bear hug, which will help make the following mobilization more effective.

Let yourself sink into the balls and slowly roll up and down your upper back (around the level of the shoulder blades). Once you find a rather tender spot or level, breathe in and out a few times while keeping the peanut directly underneath this area.

Repeat this process throughout the entire region of the thoracic spine as needed. You can likely perform this technique a few times per day if required. Keep the intensity moderate (this shouldn’t be painful). Hopefully, you’ll notice tension and stiffness decreasing after a day or two of performing this technique.

Pro tip: you can try rotating your body slightly to the left or the right to put more pressure on one side of your paraspinal muscles if needed.

Using a heating source

Opting for any external heat source, such as a heating pad, can also be a nice way to decrease stiffness and discomfort. The challenge here will be that you’ll likely need to be lying on your back for this.

Nonetheless, if you can spend some time laying down on one, you’ll likely find that it’ll have a nice pain-relieving effect while helping your muscles to relax as well.

Now, if a heating pad isn’t in the cards for you, but you still want to lay on something and get pain-relieving effects, you might want to look into an acupressure mat, as they have been shown to provide pain-relieving effects, reduce inflammation, and promote general wellbeing.4–6 They’re relatively inexpensive, and for me personally, I lay on mine whenever my upper back just feels like it could use some TLC.

If you want to learn more, you can check out my articles:

- Six Benefits of Using an Acupressure Mat for Your Aches and Pains

- Using an Acupressure Mat: Five Pro Tips for Greater Pain Relief

Final thoughts

While it may initially seem a bit perplexing — or even concerning — as to why your mid or upper back gets sore after doing a lower body exercise, there’s usually nothing too unusual about this occurring. Front squats require various muscles of the upper back to contract much more aggressively than traditional back squats due to the weight being in front of the spine rather than over the top.

So, don’t freak out if you’ve only got some generalized muscle soreness. Follow the tips in this article to recover quicker and ensure that your upper back becomes more robust for future front squatting sessions!

References:

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!