The front rack position (often just called the rack position) is a lifting position you will need to get good at if you’re someone who wants to do exercises such as barbell front squats, cleans, push presses, push jerks, or various overhead barbell pressing exercises. It’s too valuable not to be able to execute.

But it can often be uncomfortable or even painful on a lifter’s collarbone (especially newer lifters). So, this article will walk you through the necessary information to help you better understand why it happens and how to resolve the issue.

Collarbone pain from front squats typically results from poor technique and bad placement. It can also result from not being accustomed to the exercise or conditions involving the collarbone joints. Simple modifications and technique improvement can usually remedy the issue.

With a bit of practice and some patience, you’ll likely stand a good chance of getting to a pain-free front squat, provided you don’t have a history of nasty injuries to your collarbone or a degenerative condition such as clavicular osteolysis (covered within this article).

So, give this article a read if you’re serious about getting your collarbone pain under control when doing front squats!

Related article: Why Your Upper Back Gets Sore From Front Squats (And How to Fix it)

Basic collarbone anatomy

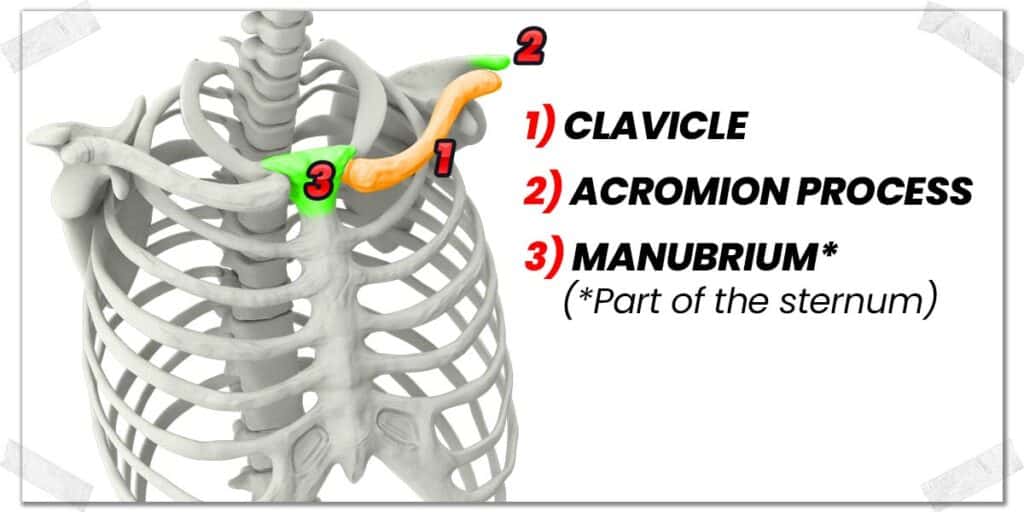

The collarbone is anatomically known as the clavicle (but I’ll just call it the collarbone for this article). It is attached at each of its ends to other respective bones. The inside edge is attached to a bone called the manubrium (which sits on top of your sternum).

The outside edge is attached to a bony projection on your shoulder blade called the acromion process (often just called the acromion). The joints on each end of the collarbone are held together by thick connective tissue known as ligaments.

(A basic awareness of these joints will come in handy later on in this article when I discuss potential causes of collarbone pain.)

Ideal front rack position

There’s no need to make this overly complex with this blog article. A good rack position allows the barbell to rest securely above your collarbone in a way that doesn’t cause excessive discomfort.

You don’t want to get in the habit of trying to hold the bar with your elbows beneath you—this will cause all sorts of physical problems for your arms and shoulders and technique errors with your squats.

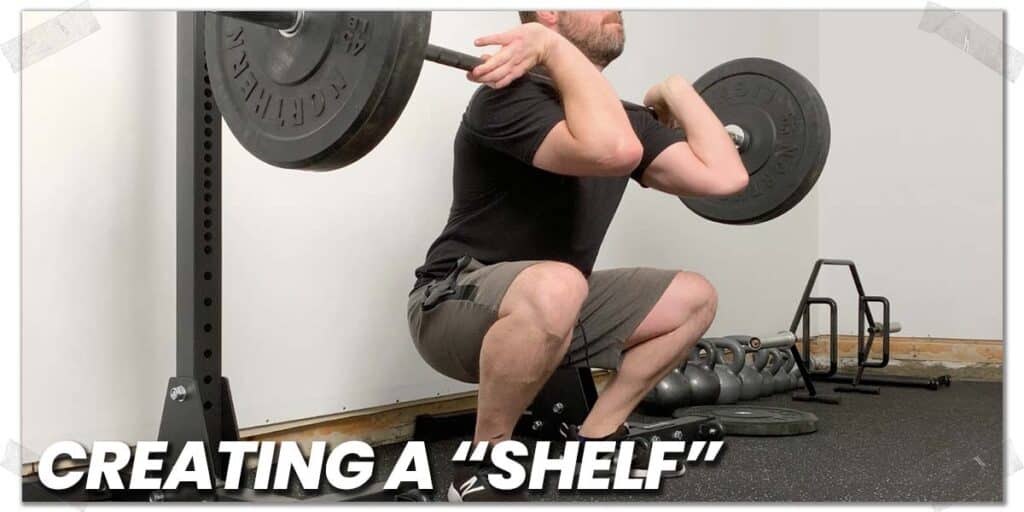

Typically, you’ll want your elbows pointed straight out toward the wall in front of you; this creates a “shelf” that keeps the bar secure; a barbell that rolls around or moves on your collarbone while squatting feels terrible. If you don’t yet have the wrist or shoulder mobility to achieve this position, be sure to check out the front squat modifications listed in one of the sections below.

This shelf position will also make it easier for you to keep your torso upright when descending into the squat, which will save your back a world of trouble.

RELATED CONTENT:

Causes of collarbone pain

There can, of course, be numerous reasons why you’re experiencing collarbone pain with your front squats, and I certainly can’t cover them all within a single article. What follows below are some of the more common reasons I see athletes and active individuals have discomfort or pain when squatting with a barbell across their collarbone.

“It seems that individuals who compete in an overhead sport AND perform weightlifting activities are at the highest risk of getting distal clavicular osteolysis.1,2 As such, teenagers and those in their second and third decades of life seem to be at the greatest risk.”

Cause 1: You’re new to front squats

If you’re new to front squats (or any other exercise in which the barbell rests across the front of your shoulders), and you’re experiencing discomfort along your collarbone region, you may not be doing anything wrong.

It may be that you simply need to give the exercise a bit more time; many lifters find the barbell front squat to be uncomfortable or unnatural feeling at first, but soon after get used to how things feel and no longer have any issues after that.

Pro tip: if the barbell front squat just isn’t your thing, you may want to opt for goblet squats using a heavy dumbbell or kettlebell.

Cause 2: Barbell movement

The barbell should be relatively secure and in place throughout the duration of your squat. Ideally, you’ll want to ensure that it’s resting almost behind the top edge of the collarbone rather than directly on top. Resting the barbell directly on the top edge of the collarbone can be extremely uncomfortable, especially since it will be prone to move around slightly as if it were a steamroller rolling back and forth over an area without any soft tissue padding (such as muscle). Ouch!

If you find that you can’t get the barbell to sit still/in a comfortable spot during your front squats, you’ll definitely want to check out the modifications below and give them a try.

Cause 3: Collarbone joint issues

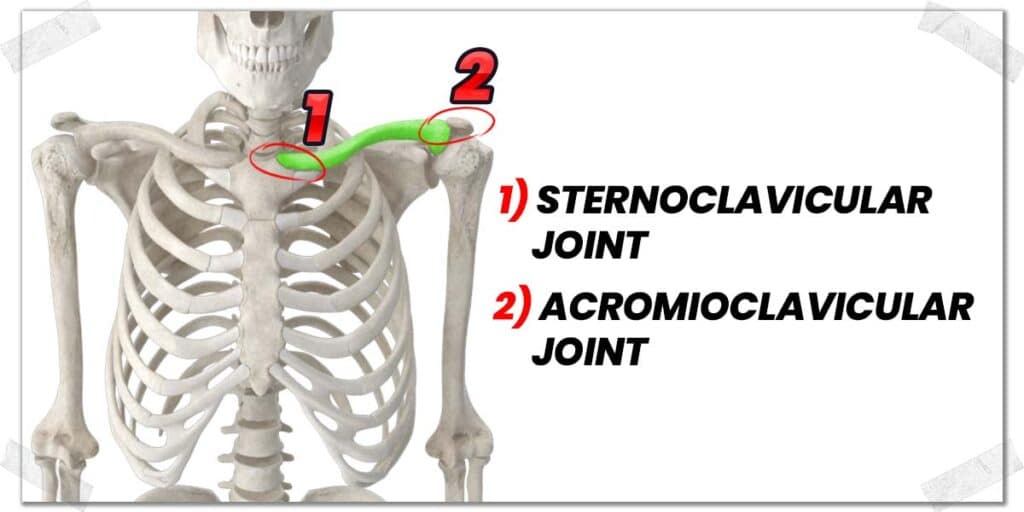

There are two separate joints of the collarbone—one at each end. The joint closest to your chest or midline of your body is known as the sternoclavicular joint. The joining closer to your shoulder is known as the acromioclavicular joint. Let’s look at them in a bit more detail.

The sternoclavicular joint

The sternoclavicular joint is the articulation of the clavicle with the manubrium. By nature, this joint has minimal natural movement it produces—but it does move. Typically, this joint is not a common source of pain unless there’s been direct trauma. Even arthritic pain arising from this joint is rarely reported. As such, I won’t be covering this joint in this article. Instead, I’ll devote more attention to the MUCH more commonly implicated joint—the acromioclavicular joint.

The acromioclavicular joint

If you’ve ever heard someone saying they hurt their “AC” joint, they’re using the abbreviated name for the acromioclavicular joint. This is the joint that forms between the end of the collar bone and the acromion process (which is essentially the roof of the shoulder blade).

The AC joint should be able to wiggle and move a tiny little bit when producing various arm movements. However, it can often get a bit jammed up, which can then produce discomfort when it otherwise needs to roll and glide to its relatively small extent.

The AC joint is also prone to becoming sprained (the same type of injury as when you roll and sprain your ankle). If you have a history of injuries (discussed below), the joint may now be a bit lax and wiggle too much, which can, again, lead to pain or discomfort if weight is pressing down on the joint.

If your pain is coming from a stiff AC joint, a qualified manual therapist (such as a physical therapist) can likely help restore some movement with some specific hands-on treatments.

Pro tip: AC joint pain is often exacerbated when the arm is pulled directly across your chest or raised directly above your head. Both of these positions maximize the congruency of the joint (pushing the joint together), which can result in pain if the joint is already unhealthy or irritated.

Read below if the joint is perhaps moving a bit too much.

RELATED CONTENT:

Previous injuries

If you have a history of injury or injuries to your AC joint, you may have had a separated shoulder (which, I’ll mention, is NOT the same as a dislocated shoulder). A history of a significant (or multiple significant) trauma and injury to your shoulder (and likely your AC joint by proxy) can lead to instability or dysfunction of your AC joint.

I’ve seen lifters with hypermobile (loose) AC joints experience collarbone pain during front squats (and cleans) due to compromised integrity of the joint.

If it’s determined that your pain is the result of a hypermobile AC joint, there really aren’t any quick fixes. You’ll likely want to modify your front squats in ways that allow you to perform the exercise without pain (see the modifications below).

Prolotherapy may be an option to help tighten up the joint, but only a qualified healthcare practitioner can determine if this is an appropriate intervention for you.

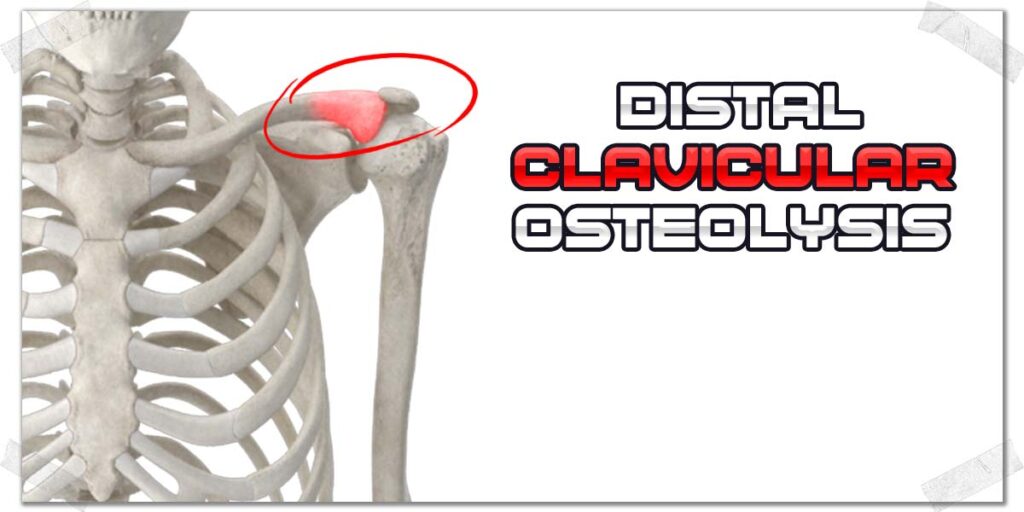

Distal clavicular osteolysis

I might as well throw one gnarly-sounding collarbone issue into the article. It’s not the most common shoulder issue out there, but since it’s most commonly found in active individuals—particularly those who perform weightlifting exercises—it’s worth briefly mentioning.

Distal clavicular osteolysis (DCO) is a condition believed to primarily result from shoulder overuse. It can arise due to trauma; however, atraumatic (without trauma) DCO is also common.

It seems that individuals who compete in an overhead sport AND perform weightlifting activities are at the highest risk of getting DCO.1,2 As such, teenagers and those in their second and third decades of life seem to be at the greatest risk.

In one study by Roedl et al., 1,432 shoulder MRIs that had been performed on teenagers who had shoulder pain were reviewed 6.5% (93) of these MRIs showed DCO. 70 were male, and 23 were female.2 So, while it’s not as common as many other shoulder pathologies (conditions), it isn’t unheard of, either.

Signs and symptoms of distal clavicular osteolysis

The condition typically presents as an aching pain in the acromioclavicular joint region. The area can be tender when touched and often becomes sorer when weightlifting. The cause of DCO is believed to be from repeated microtrauma to the subchondral bone (bone underneath the cartilage) and the body’s multiple attempts at repairing the repeated microtrauma that the bone has undergone.1

Conservative treatment for distal clavicular osteolysis

The good news is that according to the study by Roedl et al., 93% of individuals with DCO responded to conservative treatment measures (such as physical therapy). This means that if it’s confirmed that you have DCO, some temporary activity modifications and conservative therapy will likely be highly beneficial.

Bonus tip: If you’re experiencing collarbone pain when performing cleans or power cleans, make sure you’re not letting the bar crash down on your shoulders; this happens when you pull the barbell slightly higher than you need to, causing the bar to fall downwards and “crash” or drop down onto your collarbone.

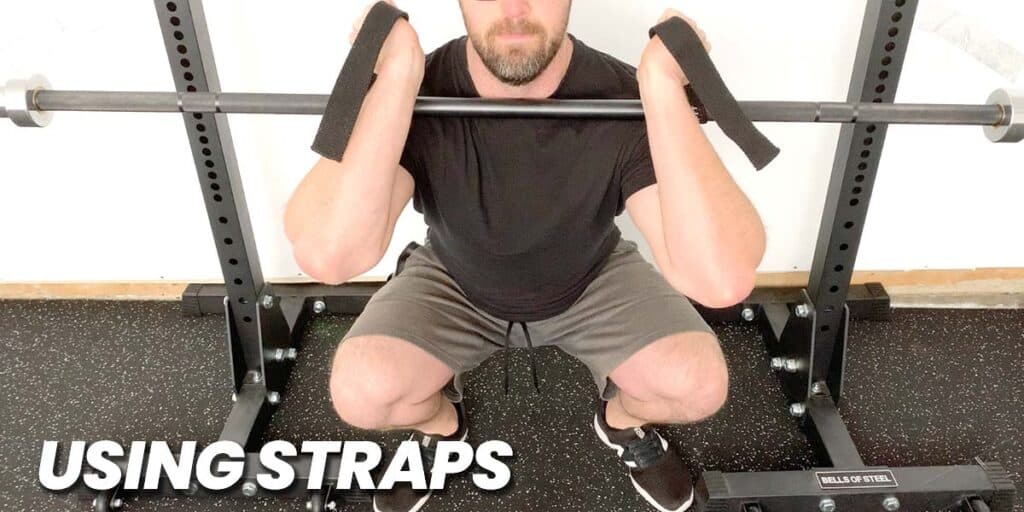

Modification 1: Creating handles for the barbell

If the traditional front rack position irritates your collarbones (or you lack the shoulder and wrist mobility to hold this position), creating a pair of handles that wrap around the barbell is likely something worth trying.

By creating a pair of vertical handles to hold onto, you can not only lessen the amount of weight resting on your collarbone (minimally, but perhaps noticeably), but you can often create a better “shelf” by increasing the amount of shoulder flexion you can attain.

There are a couple of different ways you can create some handles, but the most common (and convenient) method is to take a pair of lifting straps and loop them around the barbell (using two hand towels can work great if you don’t have straps).

If you haven’t used lifting straps before, typically, they are looped around your wrist (and thereafter wrapped onto the barbell) to prevent your grip from giving out when lifting heavy.

Instead, we’re now going to loop the straps around the barbell like in the first image in this section.

Now, you’ll have some handles to grab onto, which can perhaps help alleviate some of your collarbone discomfort. You may find that you can now control the barbell better as well, which can further help reduce discomfort from the bar otherwise moving around across your skin, shoulders, and collarbone.

Modification 2: Pool noodle padding

If handles aren’t your thing, extra padding may be. There are a few different ways to create more of a cushion between you and the barbell, all of which can be highly effective. My preference for many of the athletes (particularly those new to barbell front squats) I work with is to use a pool noodle.

Yes, there are dedicated barbell pads you can buy; however, there can be two potential issues with this:

- They cost more money than what I’m about to show you.

- They’re typically not long enough to pad your collarbone since they’re designed to rest on your back when performing the barbell back squat.

So, the solution here is to buy a pool noodle (you know, one of those bright-colored floaty toys you see kids using in swimming pools?).

With a pool noodle, you can cut it to the exact length best for you. Typically you can make a couple of these pads out of a single noodle, which will literally only cost you the same price as a cup of coffee.

You can use a larger diameter (thicker) pool noodle or one that’s smaller (thinner). Both are pretty easy to find and should last you a decent amount of time before you’ll need to switch to a newer noodle pad altogether.

And if you really wanted, you could likely find a way to place both a pool noodle and straps around the bar at the same time if you really wanted to go for all-out comfort.

Pro tip: If the gym you go to doesn’t have any barbell pads, you can easily toss your pool noodle pad into your gym bag and use it when you go there.

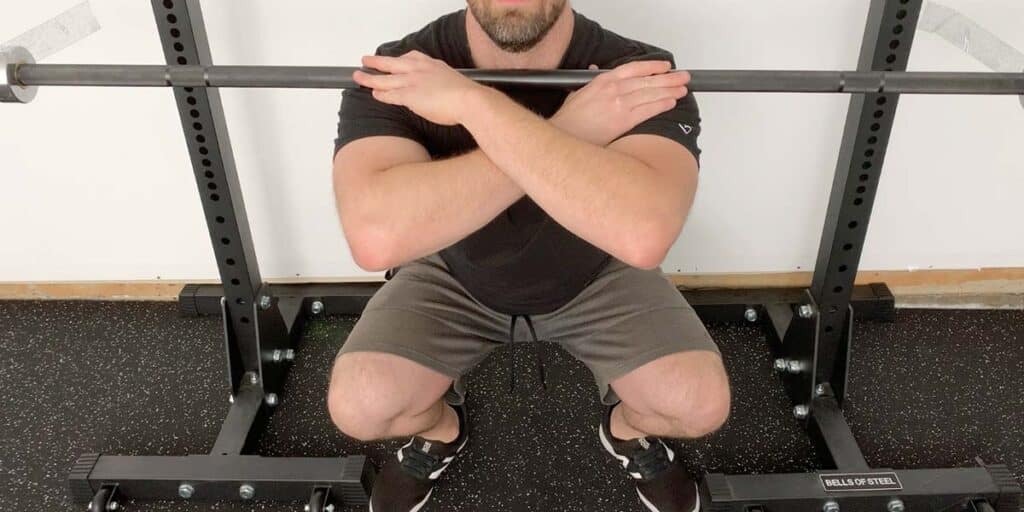

Modification 3: The California grip

If the front rack position just isn’t working for you (for whatever reason), it may be worth trying the California grip (assuming you haven’t been squatting like this to begin with). (If you’ve been using this grip and are having collarbone pain, try the first modification in this article.)

The California grip involves crossing your arms (placing them in a horizontal position) rather than the front rack position, with the arms in more of a vertical position. Though the bar will rest in practically the same location with either version, many lifters I’ve come across prefer the California grip since it can feel a bit more comfortable on their collarbone (likely because there is more of the deltoid muscle for the bar to rest on).

Personally, I’ve never been a fan of the California grip, but many of my fellow lifting friends are, and hey, this article is about you – not about me!

Pro tip: The California grip works great for front squats when you don’t have the wrist, elbow, or shoulder mobility for the front rack position.

Final thoughts

If your collarbone is giving you grief with front squats, cleans, push presses, or any other such exercise, it’s worth looking for ways to modify these exercises until you get the issue under control. These exercises can be highly valuable to those looking to build strong, powerful physiques. Don’t push through pain – look for other variations while seeking others who can help you get to the root cause of your pain.

Remember: lifelong lifters are smart lifters.

References:

1. Schwarzkopf R, Ishak C, Elman M, Gelber J, Strauss DN, Jazrawi LM. Distal Clavicular Osteolysis. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66(2).

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!