Full-body mobility is a good thing; it keeps you pain-free, healthy, and affords you the blessing of greater functionality in your day-to-day life.

Sometimes, functionality is necessary, such as when needing to be close to the ground without placing anything other than your feet. Known as the Asian squat, this position can be a tricky one to achieve, but it is worth its weight in gold.

Want to know why? Keep on reading!

In this article, you’ll learn:

- How Asian squats can help improve and maintain lower-body mobility, increase functional capacity, and prevent injury.

- Differences between the Asian and Western squat

- How Asian squats can be practiced in the gym and incorporated in your daily life when needed.

- Why individuals with a history of low back pain or hip issues should be mindful of —or avoid — performing the Asian squat.

So, if that all sounds as intriguing to you as it does to a movement geek like myself, then let’s dive right into the content!

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

What is the Asian squat?

The Asian squat refers to the deep squatting position often observed within (but not exclusive to) Asian cultures, notably when performing tasks that require the individual to be lower to the ground. It’s a position rooted deep within historical culture, long before chairs arrived on the scene or when chairs simply weren’t available.

The squat comes from the necessity to, at times, be close to the ground without resting the knees or other parts of the body on the ground; throughout history, and even today, in various locations, and for various reasons, it may not be safe or practical to do so.

But despite this, one still might find situations where being close to the ground is required. And under these circumstances, squatting is the only way to do so.

But there’s more than one way to squat down, and not all humans perform this the same way.

And if you keep reading onward, you’ll learn that there are differences within cultures for how this mandatory deep squat is required.

Related article: Hip Flexor Pain When Squatting: It Might Be More (Here’s Why)

Comparison: The Asian squat vs The Western squat

Unlike Asian culture, Western culture has long since relied heavily on the usage of chairs, benches, and other objects that eliminate the need for achieving (and holding) a deep squat position.

As such, when the need arises to squat deep, Western cultures tend to adopt a different movement strategy to get close to the floor, resulting in a different lower body position — one that looks noticeably different from its Asian counterpart.

Take a look below to see for yourself:

The most notable difference involves the heels lifting off the floor during the Western squat. Lifting the heels is a movement compensation which requires less range of motion from the ankles (and less stretching of the Achilles tendon and calf muscles), serving as a “workaround” for changing the mechanics and joint positions required to squat low to the floor.

Interestingly enough, research scientists have compared the unique biomechanical differences (differences in body positioning and movement) between each of these cultural squat patterns.

If you want to check out either of the articles, you can do so here:

- A Comparative Study on Loadings of the Lower Extremity during Deep Squat in Asian and Caucasian Individuals via OpenSim Musculoskeletal Modelling

- Comparison of the Lower Limb Kinematics and Muscle Activation Between Asian Squat and Western Squat

Benefits: why perform the Asian squat?

When performed correctly and for appropriate individuals, the Asian squat can be immensely beneficial for preserving and improving joint, tendon, and muscle health within the body. This can result in greater functional capacity of the body, fewer aches and pains, and a lower risk of injury from tissues that are otherwise unable to undergo such demands.

Let’s look at these benefits in a bit more detail.

Benefit 1: Improved joint mobility within the lower body

Achieving (and holding) the squat position requires a large range of motion involving the following joints:

- The ankles (achieving ankle dorsiflexion)

- The knees (achieving flexion)

- The hips (achieving flexion)

Restriction or poor mobility from any or all of these joints can make the Asian squat extremely difficult, uncomfortable, or even painful.

By appropriately exposing the joints to larger ranges of motion (i.e., a deeper squat depth), the tissue covering the joints, known as the joint capsule, can accommodate to these larger ranges of motion (notably in the hip) and range of motion through the joint can be enhanced (sometimes you need to stretch more than muscles and fascia!)

Benefit 2: Improved tissue compliance from tendons

If a joint within the body (such as the ankle joint) can’t work through its normal range of motion, it may not be the joint’s fault. While the tissue around the ankle, knee, and hip joint (known as capsular tissue) can indeed become stiff and immobile, a joint will also become restricted if the tendon tissue crossing over the joint is immobile.

Related article: Causes of Heel Pain When Squatting & Proven Solutions (Expert Tips)

Holding the Asian squat position can be an outstanding way to fatigue and stretch the collagen within critical regions such as the Achilles tendon or proximal hamstring tendons to help improve the tissue’s compliance (its ability to deform and accommodate into a longer position).

Restriction or poor mobility from the joints or soft tissues within the body can make the Asian squat extremely difficult, uncomfortable, or even painful.

Prolonged exposure within the Asian squat position can induce a process known as tissue creep, which is a time-dependent tissue deformation that arises when tendons and fascia (such as the Achilles tendon when held in a deep squat).

For the average Westerner, this bodyweight-loaded position can be a significantly effective way to reduce injuries to the Achilles tendon and quadriceps tendon by creating crosslink-shearing forces, notably at the junction where the tendon blends into the muscle (known as the musculotendinous junction).

Considerations: Who shouldn’t perform the Asian squat

While the Asian squat is not a harmful position for an otherwise healthy individual, there are certain populations who should likely avoid this squat altogether, be mindful of the position, or limit the overall extent to which they perform this movement.

For either of the populations below, it may be more ideal to adopt the Western squat rather than the Asian squat if absolutely necessary to get low to the ground while remaining on the feet.

Doing so can help minimize stress and strain on the lumbar spine (lower back) and the hip joint since the Western squat typically keeps the lumbar spine in a relatively neutral position and may not demand as much hip flexion due to compensation at the feet and ankles (by having the heels lift off the floor).

So, who might want to avoid performing the Asian squat?

Population 1: Individuals with a history of lower back issues

It’s not to say that individuals with a history of lower back pain should never perform the Asian squat; rather, that consideration needs to be given, particularly to those with a history of lower back pain and poor hip mobility.

Related article: Lifter’s Guide: Low Back Pain From Squatting | What to Know and do

Poor hip mobility when squatting typically results in excessive lower back flexion (rounding), which can create excessive stress and strain on the lumbar discs (known as intervertebral discs) and vertebral joints (known as facet joints).

As a result, individuals with a history of disc issues (such as bulged or herniated discs) within their lumbar spine or joint issues (notably, arthritis of the facet joints) should be very mindful about performing the Asian squat or deep squats in general.

Consideration of performing the Asian squat needs to be given, particularly to those with a history of lower back pain and poor hip mobility.

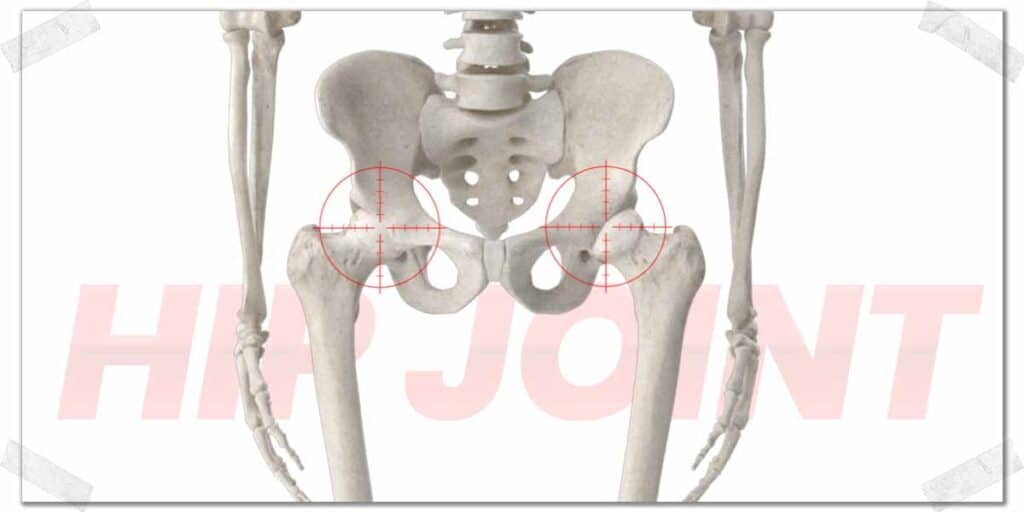

Population 2: Individuals with specific hip conditions

Since the Asian squat requires a full range of motion from the hip joint, it may not be appropriate for those with hip conditions such as:

- Osteoarthritis of the hip (particularly in moderate or advanced stages).

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) since deep hip flexion can result in bone-on-bone contact if a CAM or Pincer (or both) lesion is present.

- Labral pathology (such as a tear) that causes pain with deep hip flexion.

- Total hip replacement (deep flexion should be avoided).

If you have a known hip issue you’re not sure if it’s appropriate to perform any deep-squatting movements, be sure to check with your doctor, physical therapist, or other qualified healthcare provider.

Pro tip: individuals with knee conditions, such as osteoarthritis of the knee, or those who have had a knee replacement likely won’t favour either the Western or Asian squat due to the high degree of knee flexion (and pressure) each squat placed on the joint.

Troubleshooting: Difficulties performing the Asian Squat

If you have otherwise healthy hips but can’t comfortably get into the Asian squat position (or you find it very difficult to do so), don’t be surprised; this is the case with many individuals (particularly those in Western culture) and there can be numerous reasons for why this is.

Let’s look at the common causes of difficulty, discomfort, or pain arising with the Asian squat.

Why Asian squats are difficult for certain populations

The Asian squat requires an immense amount of hip mobility (which requires healthy hips) to drop into — and hold — the position. There are three primary reasons why the Asian squat may be difficult to achieve for those attempting to drop into this squat position:

- Genetic factors involving the depth of their hip socket

- Degenerative change or injury of the hip

- Lack of tissue compliance (stiffness) within the body

Here’s a brief rundown of each of these factors.

Reason 1: Genetic factors of the hip

Not all hips are created equal, notably with the depth of an individual’s hip socket (anatomically known as the acetabulum). The hip is a ball and socket joint, with the head of the femur (thigh bone) plugging into the acetabulum (socket) to create a joint that can move in essentially any direction.

The deeper one’s hip socket, the more limited one’s hip flexion will be. While most individuals with healthy hips, regardless of socket depth, will still be able to achieve a deep squat, not all of this range of motion will arise purely from the hip; there will be a greater degree of lumbar flexion that will take place (known as lumbopelvic flexion, but often referred to as “butt-wink”) to achieve the bottom position.

The Asian squat requires an immense amount of hip mobility (which requires healthy hips) to drop into — and hold — the position.

So, if you find it challenging to drop into the bottom of the Asian squat position while keeping your torso rather vertical (i.e., not letting your chest collapse towards the ground), it might be due to the natural composition of your hips, which you can thank your parents for.

Pro tip: you may want to play around with your foot position if you find the deep squat uncomfortable on your hips; slightly pointing your feet outwards may help create a bit of additional range of squat motion for your hips.

Reason 2: Lack of exposure to ranges of motion

This reason will apply to the vast majority of individuals, particularly those of Western culture. It’s the whole “use it or lose it” phenomenon whereby joint capsules, muscles, tendons, and fascia that aren’t routinely taken through large ranges of motion on a regular basis lose availability to these ranges.

In other words: Your muscles, tendons, joints, and other tissues within your body get really good at whatever you do. So, if you do a lot of sitting but not deep squatting, sitting won’t be an issue, but deep squatting will.

Related article: Why You Have Ankle Pain When Squatting (And How to Fix it)

Imagine not bending your elbow past 90 degrees for years and years, then one day you try to bend it further than this position — you’d notice that your elbow and likely the muscles on the back of your arm would have a difficult time lengthening out to achieve this position since they’ve adapted to only ever needing to bend up to 90 degrees.

It’s the same concept in the hips; we tend to sit with our hips flexed to 90 degrees and typically don’t bend them more than this when we’re in upright positions.

If you do a lot of sitting but not deep squatting, sitting won’t be an issue, but deep squatting will.

How to: Improving your Asian squat

Improving your body’s ability to drop into — and tolerate holding — the Asian squat is likely quite doable if you’re an otherwise healthy individual. But that doesn’t mean you have to force your body to

Here are a few strategies and tactics you can consider implementing to improve your Asian squat:

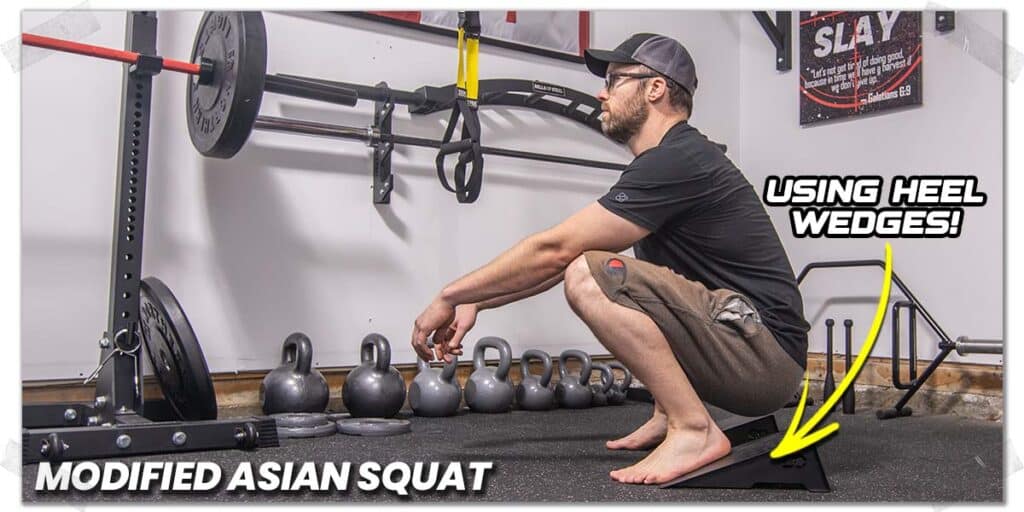

Strategy 1: Start with a modified Asian squat

The easiest way to modify the Asian squat while still remaining true to the movement is to place your heels on an elevated surface, typically one that’s an inch or two in height.

Related article: Squat Wedges: Benefits | Drawbacks | When to Use Them

With the heels resting on an elevated surface, the required amount of dorsiflexion from the ankles will be lessened, allowing most individuals to drop deeper into the squat.

Pro tip: A 2×4 or 2×6 board is a practical and convenient piece of “equipment” to place your heels on. As time goes on, you can try a 1×4 or 1×6 board, which will require more ankle dorsiflexion than the 2″ board, but not as much as if performing the Asian squat on flat ground.

Whether you take a couple of days, weeks, or even months to use this modification, it’s a great way to progress your body’s ability to drop into and maintain the deep squat position.

Strategy 2: Build up your time spent in the squat

The Asian squat is typically held for a sustained duration of time as an individual performs an activity, but as you start out, it’s perfectly fine to spend very short durations in the squat and build up your tolerance to the time you spend in this squat position.

Here’s a sample of what this strategy might look like:

| Week 1 | Asian squat 1x/day for 30 seconds |

| Week 2 | Asian squat 2x/day for 45 seconds |

| Week 3 | Asian squat 4x/day x 60 seconds |

| Week 4 | Asian squat 5x or more x 60+ seconds |

Pro tip: You can also incorporate performing small daily tasks while holding the Asian squat, such as eating a snack, brushing your teeth, etc., to afford more opportunities throughout the day to drop into this position.

Strategy 3: Perform soft tissue treatment for your muscles

This strategy is a nice little “low-hanging fruit” to go after since it can be a simple and convenient way to help your body move into larger ranges of motion (such as a deeper squat).

The main muscle groups that are practical to target and treat on your own that can help improve the Asian squat are:

- The calf muscles

- The quadriceps muscles

Both of these muscle groups (and their respective tendons) must undergo significant stretch or lengthening to permit full range of motion for the Asian squat.

Self-treatment strategies can look like:

- Foam rolling for the calf muscles

- Performing a gentle daily yoga routine for your lower body

- Performing barbell rolling for your calves (it’s intense but can work rather well – check out the video below!)

- Performing the reverse Nordic Curl to lengthen and strengthen your lower quadriceps muscles and associated tendon tissue just above your knee cap (check out the video below!)

Final thoughts

The Asian squat is one rooted deep throughout history and culture and comes with numerous functional and health-related benefits for those who routinely adopt this position.

Like anything else, it’s not appropriate for everyone, but for individuals who are otherwise healthy and are looking to maintain full ranges of motion in their ankles, knees, and hips, regularly performing the Asian squat can be an ideal action to take.

Frequently Asked Questions

To provide as much helpful information and insight as possible within this article, I’ve included a few frequently asked questions pertaining to the Asian squat and some brief answers for each one.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!