Shoulders are one of those things where you never truly realize how much you use them until they’re not working as they should. And perhaps the only other thing more annoying than dealing with a tight shoulder while trying to workout or exercise is not knowing why the darn thing is getting tight in the first place. If this is the situation you find yourself in, don’t sweat it; this article has got you covered!

Shoulder tightness is often the result of capsular tightness (frozen shoulder), various muscular issues involving the rotator cuff, pectoralis or similar muscles, arthritis of the shoulder joint, and mobility issues in the cervical and thoracic spine. Keep reading to learn how to address each issue.

When it comes to tackling the more common causes of this issue, there can be a surprising amount of information to unpack and parse through, which I will do in a straightforward and practical manner.

So, let’s start unpacking!

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

Just so we’re clear, as I kick things off here, I need to point out that the human shoulder can become stiff, tight, or otherwise restricted (all of which lead to poor shoulder mobility) for numerous reasons – far more than what I can discuss within a single blog article. Within this article, I’m covering the more prominent conditions that can affect shoulder mobility (as a physical therapist, I deal with them all the time in the clinic when treating my patients).

As always, if you’re unsure what’s causing your shoulder tightness, it’s best to get an evaluation from a qualified medical professional.

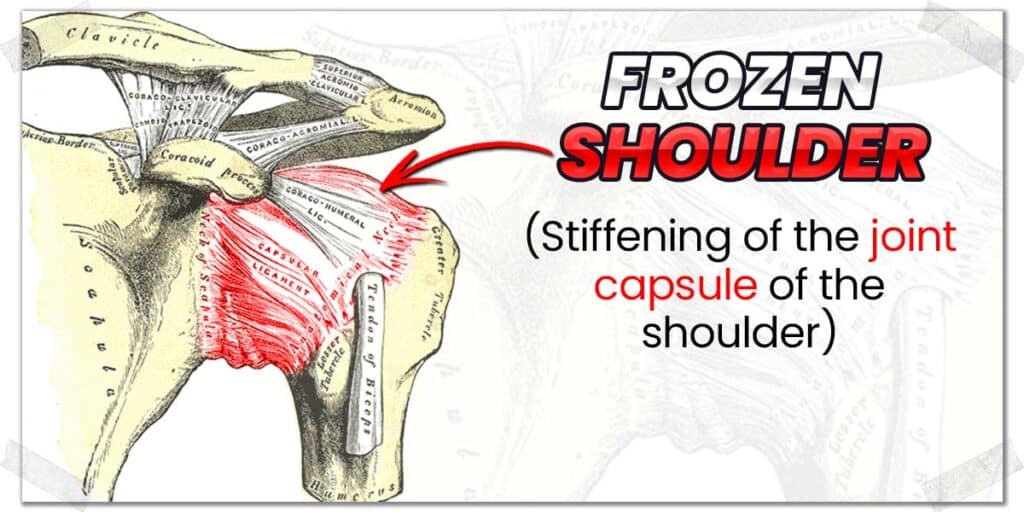

Reason 1: Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)

Adhesive capsulitis, more commonly referred to as frozen shoulder, is the epitome of feeling like one shoulder is tighter or more restricted than the other. As its name implies, frozen shoulder is a condition whereby the glenohumeral joint (the ball and socket joint of the shoulder) becomes incredibly stiff and often painful to move.

Frozen shoulder can be classified into two categories:

- Primary frozen shoulder

- Secondary frozen shoulder

Primary frozen shoulder refers to the seemingly spontaneous tightening of the shoulder capsule without any known cause (this is known as an idiopathic onset). In the scientific community, we’re not entirely certain why this occurs, though there are underlying components that are believed to make individuals more prone to experiencing a frozen shoulder.

Frozen shoulder most commonly affects:

- Females and males (females comprise approximately 70% of all cases; males are 30%).1

- Individuals between their fourth and sixth decade of life.1

- Individuals with metabolic disorders such as diabetes and thyroid issues.1–3

Secondary frozen shoulder refers to the same condition as primary frozen shoulder, with the only difference being what causes the condition to arise. Unlike its primary counterpart, secondary frozen shoulder occurs for a known reason – that reason behind due to a prolonged lack of movement, such as from having one’s arm in a sling for weeks on end.

Related content:

Treating a frozen shoulder

A frozen shoulder is an annoying issue to experience, not only because it leads to pain and stiffness in the shoulder (affecting one’s quality of life) but also because it takes some time to overcome. While the length of recovery will vary from one individual to the next, it can often take a year or longer to get the shoulder back to normal or near-normal function (some individuals are left with a mild range of motion restriction).

To gain further insight into the current consensus on causes and treatments for frozen shoulder, I would consider reading the following articles:

- Frozen Shoulder: Evidence and a Proposed Model Guiding Rehabilitation

- Frozen shoulder: A systematic review of therapeutic options

Reason 2: Rotator cuff issues

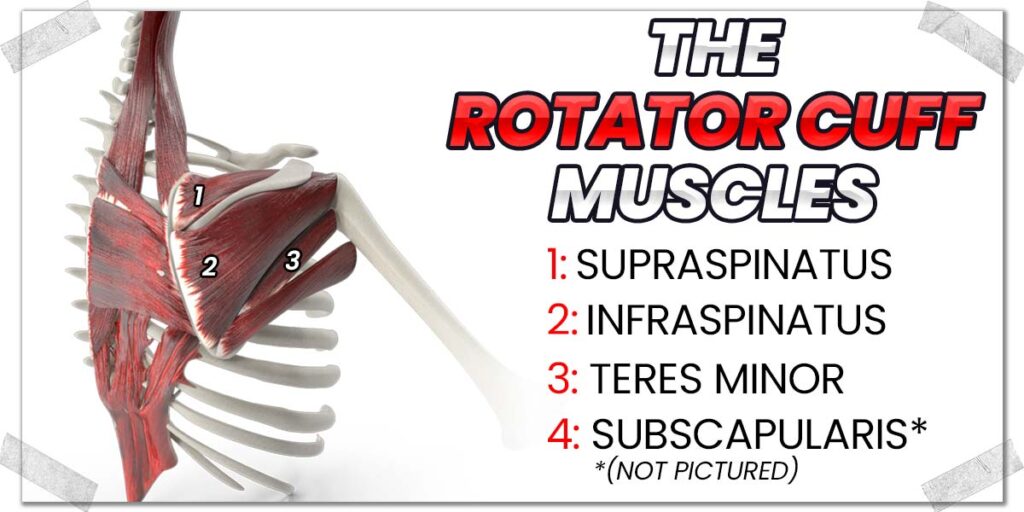

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that cross the shoulder joint and collectively work to fine-tune and “steer” movements of the upper extremity (the arm).

Movements such as reaching with, pulling, and raising the arm are mainly completed in part due to this team of smaller but critical muscles of the shoulder.

In case you want the specifics, the four rotator cuff muscles are:

- The supraspinatus

- The infraspinatus

- The trees minor

- The subscapularis

The unfortunate nature of these muscles is that they are smaller and much more delicate (and therefore, more injury prone) than the bigger, “powerhouse” muscles that cross the shoulder to produce much more forceful movement. (Remember, the rotator cuff muscles help to fine-tune shoulder movement, not to produce powerful movement.)

As a result, any of the four rotator cuff muscles can often become overworked and strained, leading to the affected muscle(s) becoming tight and painful, either of which can lead to reduced shoulder mobility and sensations of the shoulder being stiff.

Treating rotator cuff issues

Treating any type of rotator cuff issue involves improving the health of any of the affected muscles. This is most often done through conservative measures, with invasive procedures such as surgery being saved for more significant injuries, such as complete tearing of the muscle, whereby it is surgically reattached.

Conservative measures can vary notably based on:

- Which muscle(s) is/are affected

- The type of injury or pathology affecting the muscle(s)

- The extent of the injury or pathology

- Other factors unique to the individual

Generally speaking, conservative interventions are often based on the therapeutic strengthening of the muscle or tendon, particularly through loading protocols (subjecting the muscle and tendon to resistance on a routine basis).

If you want more insight into how the scientific process of improving the health of your rotator cuff muscles, check out the following scientific articles as a helpful (and reliable) starting point:

- Systematic Review: Nonoperative and Operative Treatments for Rotator Cuff Tears

- Exercise therapy for the conservative management of full thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systematic review

Reason 3: Pectoral muscle issues

There are two pectoral muscles on each side of the chest; these are:

- The pectoralis major

- The pectoralis minor

The pectoralis major

The pectoralis major is the muscle most people think of when they visualize the “pectoral” muscle. It sits on top of the pectoralis minor and is responsible for producing movement of your upper arm bone (the humerus) for motions such as pushing an object straight away from you or horizontally pulling your arm across your body.

Since the pectoralis major plays a prominent role in producing shoulder movement, tightness and generalized dysfunction in this muscle can cause the whole shoulder to feel like it’s tighter than the other.

The pectoralis minor

The pectoralis minor is the much lesser-known baby brother of the pectoralis muscles. It sits directly beneath the pectoralis major, and while it actually doesn’t cross the shoulder joint itself, it can still play a role in the sensations of a tight shoulder since it attaches to a part of the shoulder blade (known as the coracoid process).

The muscle itself often becomes tight and dysfunctional with poor posture (think rounded shoulders). Though it’s a smaller muscle, it can really gunk up certain aspects of shoulder mobility.

Because it’s underneath the pectoralis major and because it doesn’t actually cross the shoulder joint itself, it can be a rather tricky muscle to target for stretching and other therapeutic interventions. But thankfully, there is a rather economical way to receive some therapeutic massage from the comfort of your own home!

So, if you want to read up on my preferred way to improve pectoral mobility (for both pectoral muscles) in the comfort of your own home, check out my article:

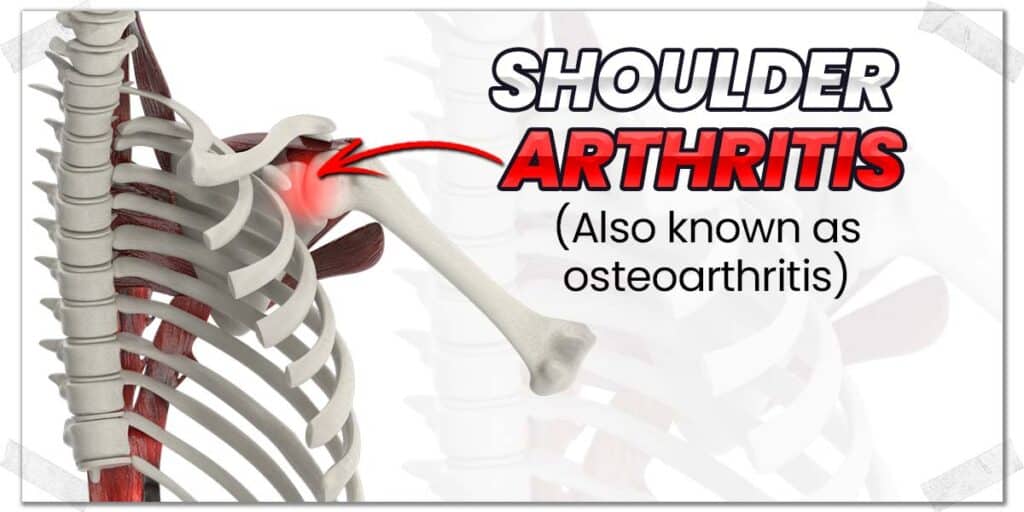

Reason 4: Osteoarthritis of the shoulder

Osteoarthritis refers to the breakdown of the cartilage that sits on top of the end of a bone, where it articulates with an adjacent piece of cartilage and its respective bone.

The purpose of this shiny, smooth cartilage is to allow the joint surfaces to smoothly slide and glide on top of one another, allowing for effortless and pain-free movement.

Unfortunately, this cartilage can break down as we age (or for other reasons), leading to pain and altered movement within the shoulder.

While osteoarthritis of the shoulder doesn’t cause the shoulder itself or surrounding tissues to become tight in a direct sense (as opposed to a condition such as frozen shoulder), the lack of health within the joint can lead to altered function of the shoulder, which can reduce the mobility of other nearby structures (such as the rotator cuff muscles, as an example).

The result can be tightness that’s felt around the shoulder, with the underlying mechanism coming from the breakdown of the joint itself.

If you want to read up more on osteoarthritis of the shoulder, check out these reputable articles (both are from the National Library of Medicine):

Treating osteoarthritis of the shoulder

Treatment interventions for an arthritic shoulder will depend on the extent or severity of the arthritis within the joint.

As a general rule, conservative measures will consist of keeping the shoulder as active as possible (through therapeutic movement and exercise) with activities that do not worsen any pain in the process.

Pro tip: the articular cartilage within a joint gets its oxygen and nutrients from the synovial fluid within the joint; it has almost no direct blood supply. As such, active movement of the joint disperses these required substances across the cartilage surface, allowing the cartilage to take in these structures and maintain its health.

When an arthritic joint is permitted to sit still, it will have a harder time staying healthy due to the decreased disbursement of synovial fluid within the joint.

What these therapeutic movements will consist of will depend on the extent of arthritic change within the individual’s joint.

As such (and as always), your best bet will be to get your therapeutic exercises prescribed to you by a qualified healthcare professional.

If things are really nasty, a partial or full shoulder replacement (a surgical procedure) may be warranted. However, this topic is far outside the scope of this article.

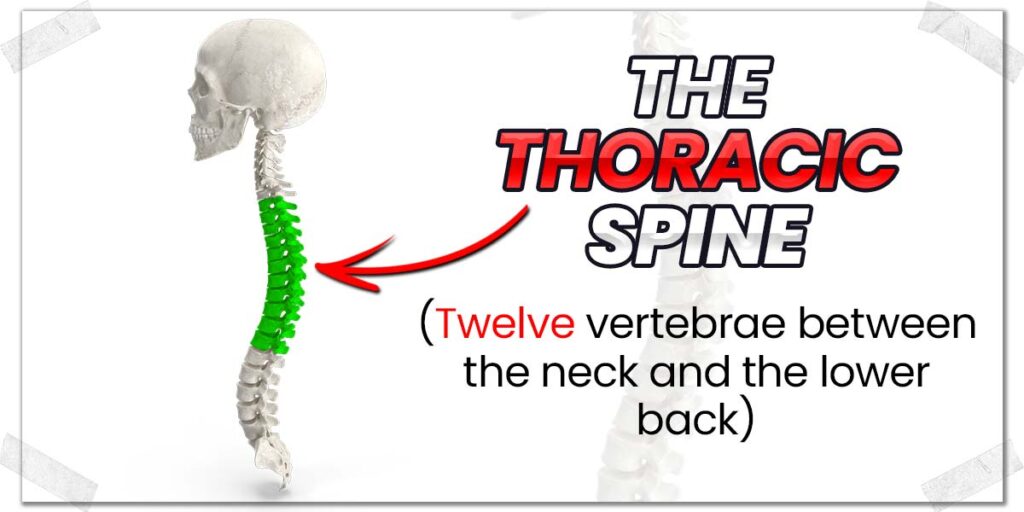

Reason 5: Thoracic spine mobility issues

The thoracic spine refers to the twelve vertebrae (spine bones) that comprise the middle and upper portion of your back.

It may sound strange to think that the middle and upper back may cause tightness in one of your shoulders, but as you learn more about (and understand) human anatomy and physiology, it becomes quite obvious that impaired thoracic spine mobility can significantly impact shoulder function.

The shoulder blade (which forms part of the shoulder joint) is, in part, held in place by the muscles that attach to it from the thoracic spine (which is known as the scapulothoracic joint). While it’s not a true articular joint (it doesn’t have a direct bone-to-bone articulation), the muscles that run from the thoracic spine and attach to the shoulder blade form a joint-like dependency with one another (making it classified as a physiologic joint).

That may sound a bit complex, but all it means is that if the thoracic spine can’t move as freely as it should, the muscles running from the spine to the shoulder blade likely can’t move as freely as intended, which, in turn, can gunk up mobility around the shoulder itself.

As an example: a thoracic spine that doesn’t extend (straighten) as much as it should will ultimately limit how high you can lift your shoulder overhead, which can lead to a greater sensation of stretching or effort taking place in your shoulder as you lift it to the end of its available range of motion.

Likely, a stiff thoracic spine won’t directly influence the mobility of your shoulder joint itself. Still, it will indirectly affect it by impairing the movement of the shoulder blade. As such, improving and, ultimately, restoring any mobility lacking in your thoracic spine can help reduce sensations of tightness around your general shoulder region.

Treating thoracic spine issues

If it’s simply a matter of the facet joints within your thoracic spine being a bit stiff and immobile, a dedicated thoracic spine mobility regimen can often clean things up quite nicely. It will likely take a bit of time, but with a few key exercises that challenge the mobility of the facet joints within your thoracic spine, you’ll likely notice some substantial improvements.

There’s an absolute plethora of therapeutic exercises out there that work to help improve thoracic spine mobility. My favourites tend to be those that are relatively simple and convenient to perform.

Typically, as adults, we don’t spend enough time rotating or extending (backward bending) this region of our back, so exercises and movements that work to counteract this issue tend to work quite well.

These types of therapeutic movements can include:

- Open book rotations (improves rotation)

- Child’s pose (improves extension)

- Thoracic spine foam rolling (improves general movement)

There are plenty of YouTube videos out there on each of these movements, so simply type any of those terms into the search bar and you’ll likely be met with some quality videos that walk you through how to perform each one.

Remember: A therapeutic exercise routine for improving mobility can take some time. Try to carve out approximately ten minutes four or five days per week for these types of restorative movements. Results will likely be evident after a few weeks.

Final thoughts

Experiencing a shoulder that is tighter or stiffer feeling than the other isn’t an uncommon issue; physical therapists such as myself see these types of issues in the clinic on a regular basis.

Frequently Asked Questions

I like to be as helpful and informative as possible in my blog articles, as I want you to live an active and pain-free life to the best extent possible. So, I’ve included some brief answers below to a few frequently asked questions regarding shoulder tightness.

References:

1. Ewald A. Adhesive capsulitis: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(4):417-422.

2. Ryan V, Brown H, Minns Lowe CJ, Lewis JS. The pathophysiology associated with primary (idiopathic) frozen shoulder: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):1-21.

3. Le HV, Lee SJ, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments. Shoulder Elb. 2017;9(2):75-84.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!