Strong, chiseled abs will never go out of style, but the most popular exercise for achieving them – the sit-up – certainly has. While a carved-up set of abs is indeed considered to be quite sexy, debilitating lower back pain certainly isn’t. And according to science, that might be what you’re in for if you keep performing them as part of your fitness routine.

Here’s the quick, one paragraph rundown on what you can learn within this article:

Research shows that the traditional sit-up exercise can be detrimental to the health of the intervertebral discs in the lower spine. Poor disc health can lead to extensive pain, injury, and dysfunction. Other exercises have been scientifically proven to be more effective and safer than sit-ups.

So, if that preceding paragraph comes as a bit of a surprise to you, bums you out, or makes you wonder what the more ideal exercises are to do instead (according to science), then you’ll absolutely want to read the surprising details below!

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

Related content:

As we dive into things, there are a few critical points to be aware of as you make your way through this article:

- I’m not universally against sit-ups, per se. However, for the average person, I feel there are plenty of other abdominal-based exercises that are incredibly effective for targeting these muscles while avoiding the potential lower back risks altogether. As such, they’re typically not my first go-to when programming exercises for my athletes in the gym or patients within the clinic.

- Human beings are incredibly diverse. Not everyone who performs sit-ups will experience back pain as a result. Still, when we look at the mounting collective body of evidence, it seems to be that the more repeated spinal flexion one does throughout their life (such as when performing sit-ups), the greater the chances of experiencing adverse mechanical issues of the spine and the lower back.

- Experiencing lower back pain from sit-ups might not be a sudden or instantaneous pain that you feel in the moment of the exercise or after performing them for a week or two. Much of the detrimental effects to the discs or joints of the lumbar spine can be the result of repeated spinal flexion that has taken place over weeks, months, or even years of performing sit-ups.

- The particular lower backs that are likely at the greatest risk of being adversely affected by the sit-ups are those that already have pre-existing conditions, often which can be asymptomatic (not producing any symptoms) or those with a previous injury or episodes of lower back pain.

Alright, with that being said, we next need to look at the basics of lower back anatomy, assuming you want to understand (and get the most out of) the contents of this article.

Pro tip: in addition to reading this article, I’d highly advise you to pick up the book Back Mechanic: The Step By Step Method to Fix Back Pain by Stuart McGill, particularly if you’re having any lower back pain.

The basics: Lower back anatomy

If we’re talking about the health of your lower back, we need to start with the involved anatomy; this article will be of very little use to you if I keep referencing and mentioning particular parts of the back that you’re unfamiliar with. So, don’t skip this section.

I’ll keep things quick and brief, but be aware that a basic anatomical understanding of your lower back is imperative since it will help make the concepts and considerations discussed within this article much more intuitive, allowing you to get more out of its contents while providing you with better overall outcomes.

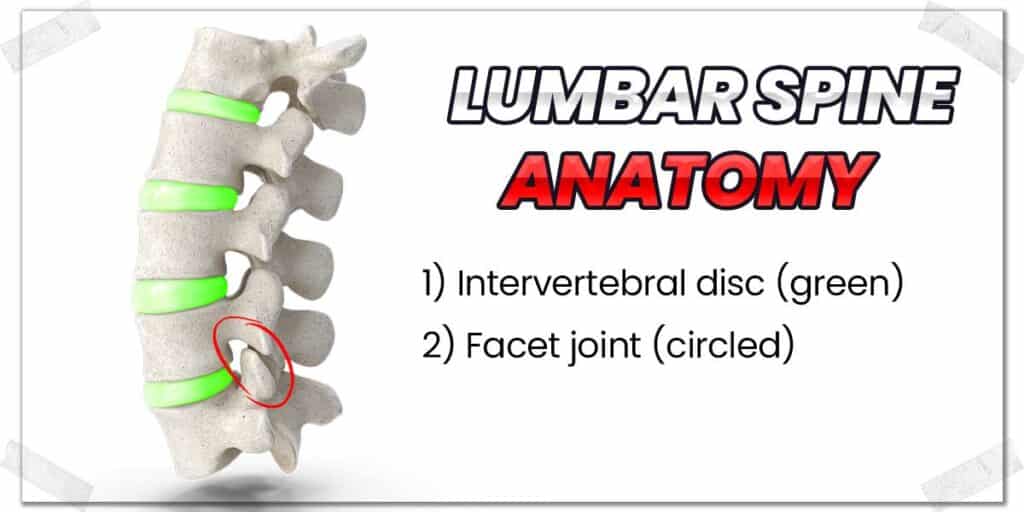

As we dive into things, the first term to be aware of is the lumbar spine. This refers to the bottom five vertebrae (spine bones) within the spinal column.

There are three critical anatomical structures we need to discuss for a preliminary understanding of how sit-ups can be harmful to the lower back.

These structures are:

- the intervertebral discs;

- the facet joints;

- the nerve roots.

Let’s quickly run through the absolute basics of each.

Structure 1: Intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine

Let’s start off with the intervertebral discs of the spine. They are, after all, the main structure that can be adversely affected with sit-ups (however, the facet joints can also be affected – which aren’t within the scope of this article).

The purpose of these discs is to help provide load-bearing capacity and integrity of the spine; merely having a bunch of bones stacked directly on top of one another without any disc tissue in between wouldn’t make for a very comfortable or capable spine. There are five of these little discs in the lumbar spine.

On the outside, the intervertebral discs are tough pieces of fibrocartilage that resemble the shape of little hockey pucks, which sit in between each vertebra. This outer portion of the disc is reinforced through annular fibers, which weave through the cartilage as if providing a structural net to reinforce the disc’s integrity.

The center of each disc contains a jelly-like substance, which is known as the nucleus pulposis. The common analogy employed here is that this nucleus is like the jelly in the middle of a jelly donut.

Under certain conditions (such as poor mechanics and aging), the contents of the lumbar discs are prone to deforming and collapsing, which can lead to a host of painful and debilitating issues. The specifics of how and why this occurs will be covered in the following section.

Structure 2: The facet joints of the lumbar spine

The facet joints (also known as zygapophyseal joints…wow, that’s a mouthful) are what allow one vertebra of the spine to link up with the respective vertebra above or below. These joints are present on every vertebra from your neck down to your last lumbar vertebrae.

In the lumbar spine, the facet joints are oriented in a forward and backward direction, which is what allows your lower back to bend forwards and backwards. Take note of this, as the excessive rounding of the lower spine that often occurs with the sit-up can be very taxing for these joints (more on that in the following section).

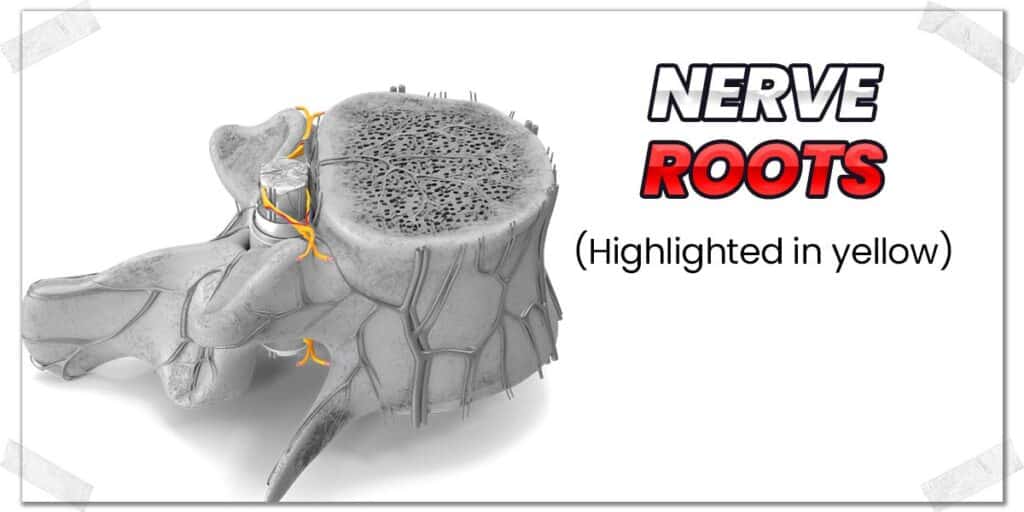

Structure 3: Nerve roots of the lumbar spine

Nerve roots are the initial projections that stem off the spinal cord (which is protected within your vertebrae). These nerve roots branch off the spinal cord and exit through a small opening (known as the intervertebral foramen) between the vertebrae above and below. The nerve root then continues on to form its respective nerve that runs down into your leg.

When things go wrong in the spine (details in the following section), the lumbar nerve roots can take the brute of the punishment, which can lead to pain and altered sensation in the back or down into the leg. It’s not a fun situation to be in, as this type of pain can be debilitating at times.

What happens to the low back during the sit-up?

There can be a lot of moving parts to examine (both literally and figuratively) when it comes to the biomechanics of the low back and spine during the sit-up. By no means does this article intend to provide a comprehensive breakdown of these mechanics and the pathological (harmful) conditions that can arise when performing sit-ups.

Rather, this article aims to deliver the conceptual underpinnings of how sit-ups can be problematic for the lower back, and it goes something like this:

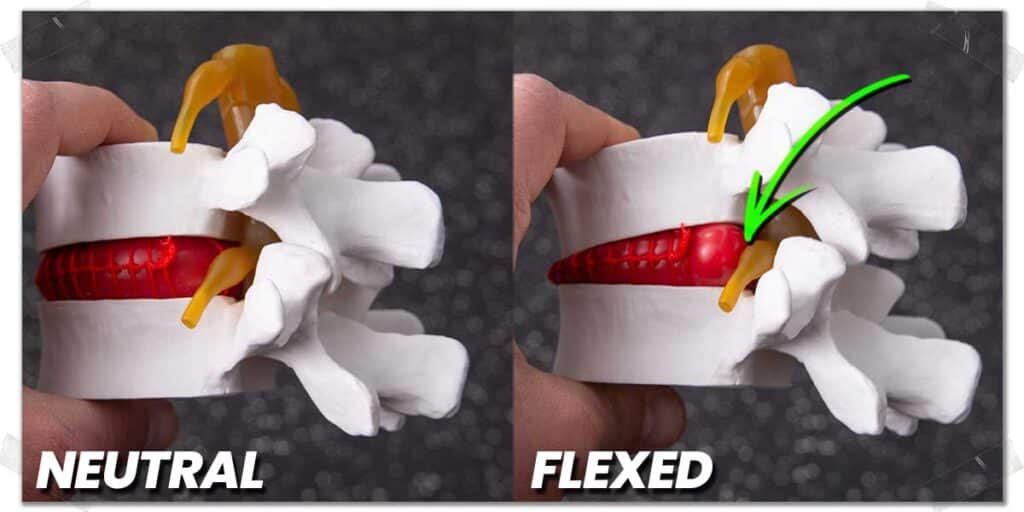

Sit-ups can place excessive compression on the front (anterior) portion of the lumbar discs, which may lead to the inner contents of the disc (the nucleus pulposis) bulging backwards, deforming the shape of the disc. This is often termed a disc herniation. This deformity can press up against the nearby nerve root, leading to pain and dysfunction in the back and leg.

Related article: Why Russian Twists Are Hurting Your Spine (And What To Do About It)

The condition of sciatica (the feeling of sharp, intense pain shooting down the back of your leg) is a prime example of this nasty phenomenon. While sciatica can arise for different reasons, one common reason is the result of lumbar disc derangement, where the disc bulges backwards, pressing up against – and irritating – the nerve root.

Again, there can be more that goes on here, but the general scenario above serves as a starting point for describing what often occurs.

What’s the research saying about the traditional sit-up exercise?

The more advanced you get in researching and understanding the lower back, the more lost you can feel. The biomechanics of the back (how the back moves and responds to these movements) is incredibly complex.

While there are multitudes of ways in which the lower back can be studied and analyzed, my approach within this article is merely to provide you with a basic foundation of what some of the most prominent low back and spine researchers have found when analyzing the joints, discs, and other associated tissues in the lower back when performing sit-ups and similar exercises.

What follows below are a few key takeaways from scientific literature examining the effects of traditional sit-ups and low back flexion on the lumbar discs within the spine:

- When examining intradiscal pressures in the lumbar spine with various exercises, bent-knee situps have been shown to produce some of the greatest disc pressures.1

- Sit-ups (either with straight legs or bent knees) have been shown to produce over 3,000 N (Newtons) of pressure on the lumbar discs when the spine is in a fully flexed position.2

- 3,000 N of pressure on the lower back exceeds occupational guidelines set by the NIOSH! (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health)3

- The overall compressive tolerance within the lumbar spine region has been shown to be notably reduced when the spine is within its end-range of flexion, such as often the case with sit-ups.4

If you want to read up more on the details of these (and other notable) findings, check out the references section at the end of this article.

Replacements: Effective alternative exercises to the sit-up

Well, now that we know how and why things can go wrong with the classic sit-up exercise, we’d better find some safer (but still highly effective) ways to train the abdominal muscles without irritating or blowing up your low back in the process.

Thankfully, some highly challenging and effective exercises can serve as effective alternatives to sit-ups. Let’s take a look at what they are!

Keep in mind: there are plenty of challenging and effective exercises that can be performed to strengthen the abdominal muscles. The ones I’ve included below are all designed to keep low back movement non-existent to minimal at all times, making them ideal for those who want to challenge their abdominals without flexing or rounding their lower back.

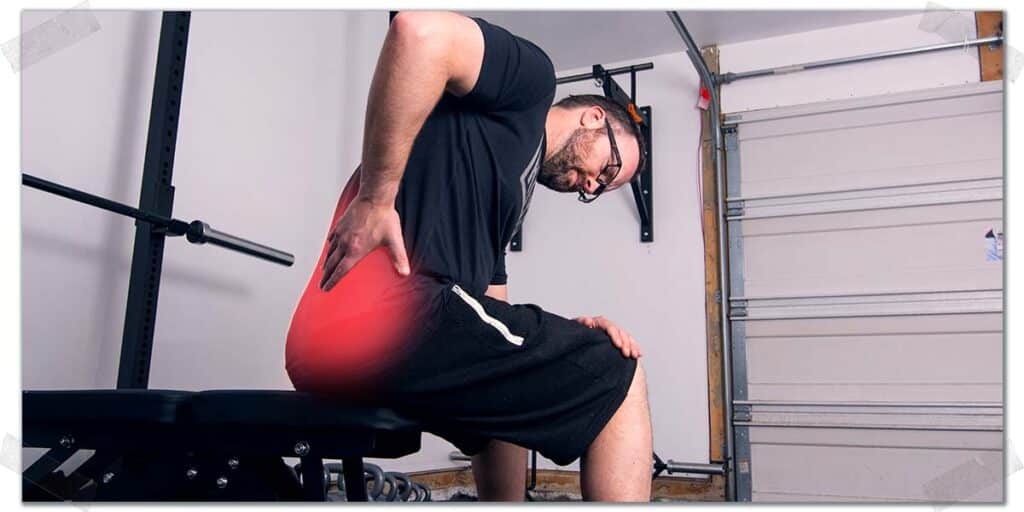

Exercise 1: The McGill Curl-up

The McGill curl-up is an exercise that has been devised by Dr. Stuart McGill, one of the world’s foremost experts in the field of lower back and spine health.

The exercise works by targeting the abdominal muscles without the need to flex or bend the lumbar spine. It’s one of his renowned “big three” exercises that has taken over the world of lower back health in recent years.

How to perform the McGill curl-up:

- Lay on your back with one leg straight and the other bent so that your foot is flat on the floor (it doesn’t matter which leg is bent).

- Place your arm underneath your lower back while keeping your lower back in a neutral position (don’t arch it or push it into the floor, either. Having your hand underneath your lower back will help you to feel if your lower back moves during the upcoming movement (you don’t want it to move).

- Keeping your neck in a neutral position (don’t curl your chin to your chest or let your chin poke upwards towards the ceiling), lift your shoulder blades off the floor, going as high as possible without moving your neck or lower back.

- Hold this top position for a second. Slowly lower yourself back to the floor and repeat for your remaining repetitions.

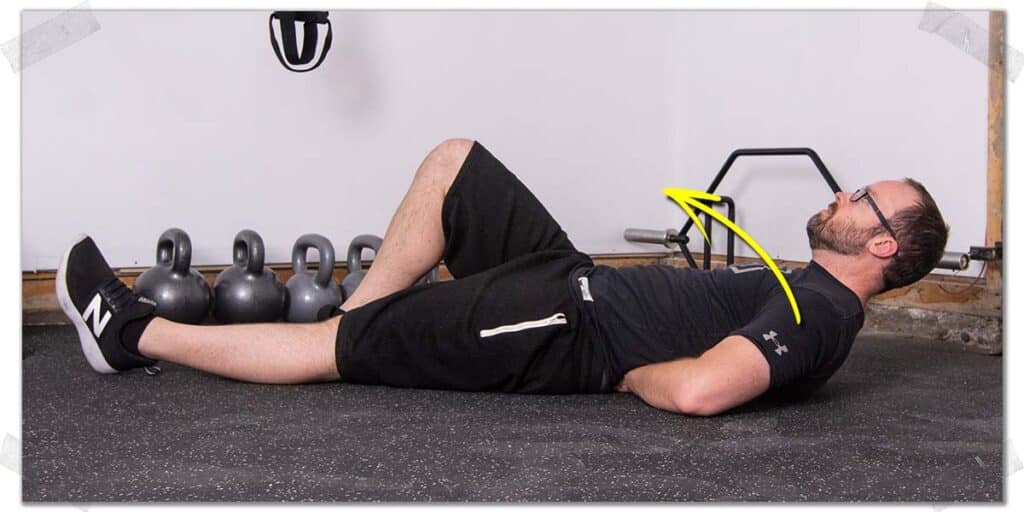

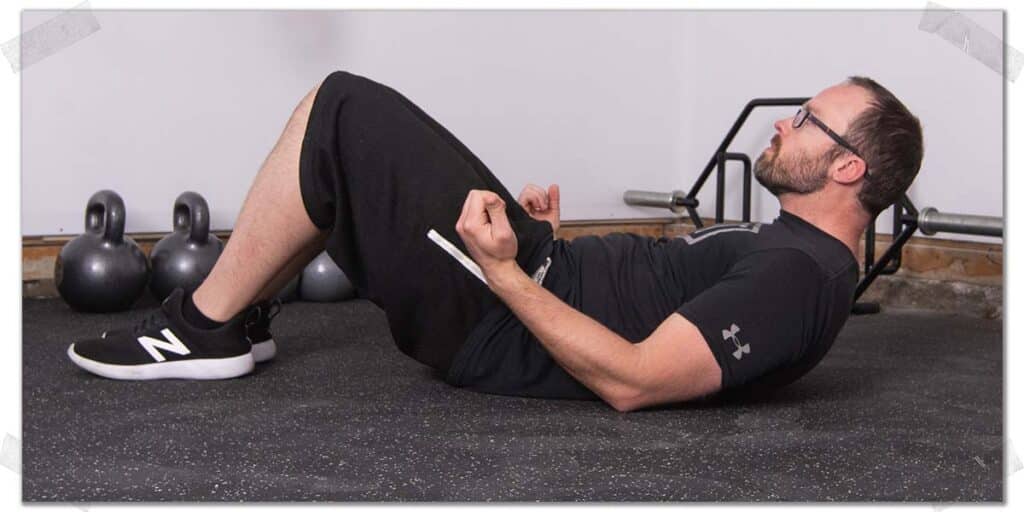

Exercise 2: Elbow Curl-ups

Elbow curl-ups are quite similar to the McGill curl-up in that they minimize lumbar spine movement while providing greater isolation to the rectus abdominis muscles. I often use them for many of my athletes and clients who want to perform some dedicated ab work without putting any excessive flexion-based movement into their lower back.

How to perform elbow curl-ups:

- Lay on your back with your hips and knees bent so that your feet are flat on the floor.

- Place your arms directly by your sides with your palms facing up (this will ensure the tips of your elbows rest on the floor).

- While keeping your neck in a neutral position (don’t tuck your chin to your chest), lift your shoulder blades up off the floor with an abdominal crunch motion.

- Crunch up as high as you can without letting your elbows come off the floor. Once you’ve gone as far as you can, return to the starting position and repeat.

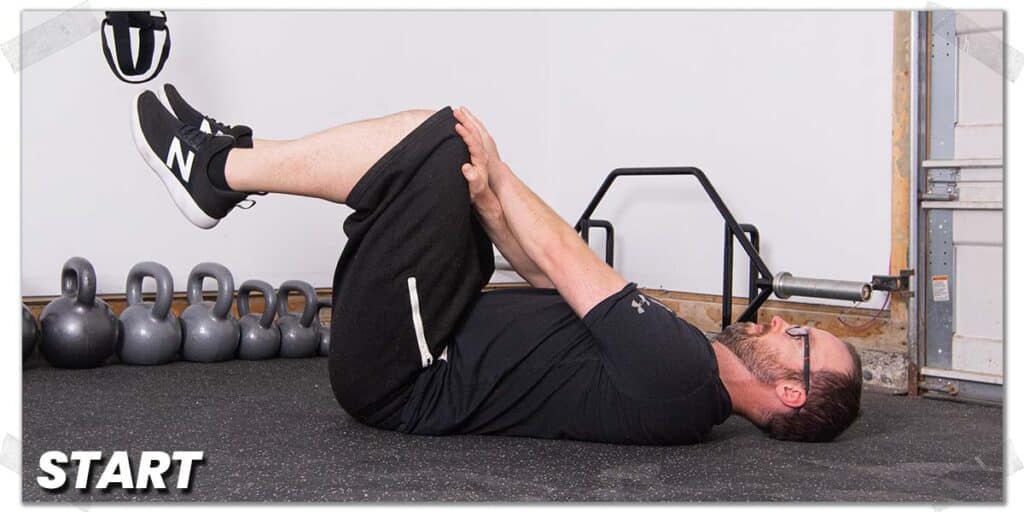

Exercise 3: Self-resisted dead bugs

The self-resisted dead bug is one of my favourite core strengthening exercises, and it’s one that I’ve had a lot of success with for my patients in the clinic and athletes in the gym. It takes the traditional dead bug exercise and kicks it up a notch.

It’s as challenging as you make it, which is one of my favourite things about it.

How to perform self-resisted dead bugs:

- Lay on your back and bend your knees and hips to 90 degrees. Keep your lower back in a neutral position (don’t let it arch, and don’t press it into the floor, either).

- Cross your arms and place your hands on the top of your knees.

- Take your bottom arm and aggressively push it into your knee while aggressively pushing that same knee back into your hand. This will create a sense of tension around your torso.

- While holding this tension, take your top arm and slowly raise it above your head.

- At the same time, take the leg that was in contact with that hand and slowly strengthen it (straightening your knee and hip). Keep holding the tension in your torso throughout the process.

- Separate your arm and leg as far as possible without letting your lower back move at all.

- Slowly return to the starting position and repeat for your remaining repetitions before switching to perform the same movement with the opposite arm and leg.

Final thoughts

The traditional sit-up exercise may not be the almighty abdominal exercise we once thought it to be. While there’s no guarantee that it will harm your low back or cause you pain, there’s enough scientific evidence to go on suggesting that you might be better off foregoing it and opting for other exercises instead – ones that minimize lumbar flexion.

Whatever you decide, be sure to listen to your body along the way and give it the respect it deserves. The result will be less pain and more time spent training.

Frequently Asked Questions

In order to make this sit-up article as helpful and informative for you as possible, I’ve included some brief answers to some commonly asked questions that people have regarding sit-ups and their lower back.

References:

1. Nachemson AL. The lumbar spine an orthopaedic challenge. spine. 1976;1(1):59-71.

2. Axler CT, McGill SM. Low back loads over a variety of abdominal exercises: searching for the safest abdominal challenge. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6):804-811.

3. McGill SM. Low back stability: from formal description to issues for performance and rehabilitation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2001;29(1):26-31.

4. Adams MA, Dolan P. Recent advances in lumbar spinal mechanics and their clinical significance. Clin Biomech. 1995;10(1):3-19.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!