Squats make the world go around, or so I like to believe. They seem to solve a lot of life’s problems too, or at least make us feel a lot better after banging out a heavy set or two. But there are a lot of nuances with the nature of the squat, one being whether it’s acceptable or beneficial to lock the knees between repetitions. Is it good? Is it bad? Does it even matter? There can be a lot to consider here, and I will unpack all the details within this article.

But let’s start with the very, very quick answer to this common question, after which I’ll unpack all the details:

Locking the knees when squatting has advantages and disadvantages and should take into account the needs, abilities, and training goals of the squatter. It’s important to know that locking the knees isn’t necessarily the same as hyperextending the knees, the latter of which should be avoided.

Pretty much, as always, locking or fully straightening your knees when squatting all depends. To consider this issue to be a universal “right” or “wrong” is perhaps a bit myopic, at least, without considering the factors and details that must be weighed along the way.

So, let’s dive into it and unpack the details that will help you have more confidence with what you should do between each repetition of your squats.

A small request: If you find this article to be helpful, or you appreciate any of the content on my site, please consider sharing it on social media and with your friends to help spread the word—it’s truly appreciated!

A quick note pertaining to powerlifting requirements

The angle of this article from which I’m writing is in reference to general lifters and gym goers. It doesn’t take into account the knee-locking requirement that powerlifters undergo before initiating their squat in competition.

For those unaware: when attempting a squat within a powerlifting competition, the lifter must start from a fully locked knee position, perform their squat (where the crease of their hips goes below the height of their knees) and then return to a fully locked knee position.

This article is keeping things non-sporting related and looks at what happens to healthy and unhealthy knees when locking and remaining bent during the squat. So, keep this in mind.

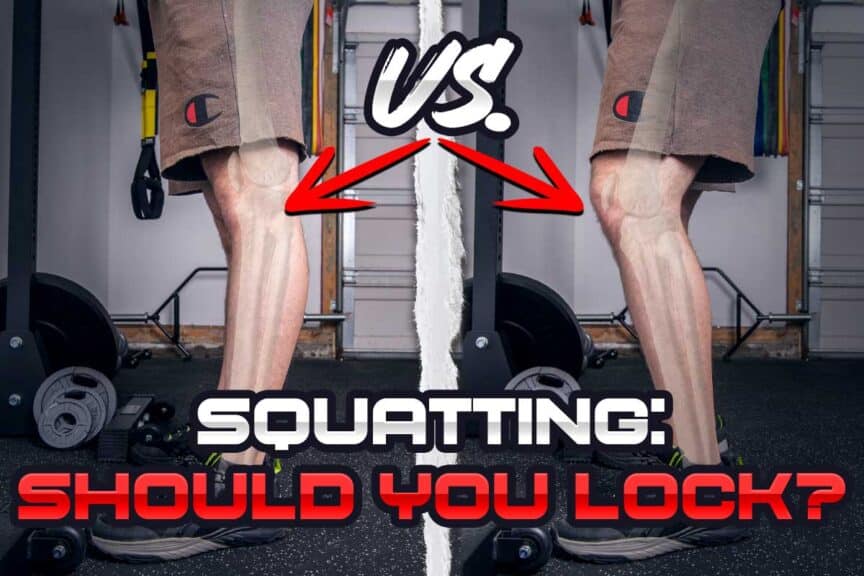

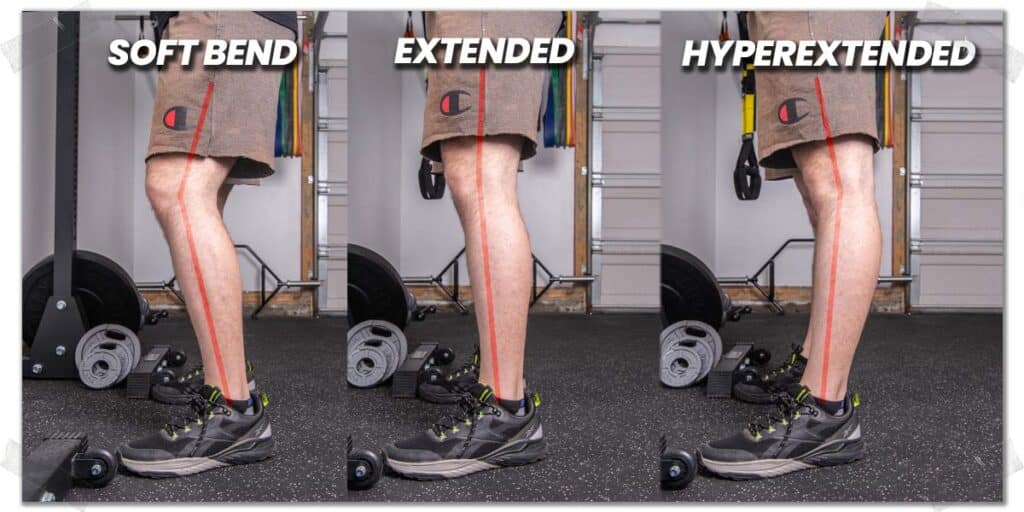

Differences: straight vs hyperextended

As I get started unpacking the contents of this article, one crucial factor that must be addressed right away is the difference between a straight knee versus a hyperextended knee. There is some semantics going on here, which is why we need to start with getting our definitions straight; if each of us is working off of a different definition of “locking” the knee, we will all misconstrue the concepts and conclusions delivered in the paragraphs below.

The knee, classified as a hinge joint, on average, has approximately 135 degrees of motion which it can “hinge” through (hinging consists of the motions of flexion and extension).

On an anatomically normal knee, we can measure this range of motion by having the knee in a fully straightened position, which is defined as zero degrees of flexion (we then bend it to see how many degrees of flexion it can produce).

However, with some knees, the knees can start beyond zero degrees (meaning it extends beyond a perfectly straight position), which means we’ve now got a case of genu recurvatum on our hands. Read the following section to learn about what’s going on here and why this matters.

Related article: Squat Wedges: Benefits | Drawbacks | When To Use Them

Genu recurvatum: Have you ever seen knees bend backwards?

Genu recurvatum is the fancy way of referring to hyperextension (backward bending) of the knee. Some individuals are more predisposed to it than others; however, most individuals’ knees can allow for a few degrees of this backward bending. Regardless of how much of it your knees can produce, we need to be mindful that it can be different (for a variety of reasons) with every lifter.

In knowing this, here’s what we must be mindful of: when a knee is in a fully straightened position at the top of a squat, it might appear as “locked” on some individuals when, in fact, it may not be; it may have a few extra degrees of hyperextension (backwards bending) it can go through before it is truly maxed out into a fully extended and truly locked position.

This is why we need to have our definitions straight of what “locked” truly is. You may think a lifter is fully extending their knees when, in fact, they’re not.

I would most certainly advocate avoiding excessive hyperextension (moving the knee beyond its zero-degree straight-line position). Not only can this hyperextend position be taxing on the cartilage of the knee joint itself, but it can also throw off the lifter’s balance (i.e., their center of gravity) between each rep.

Additionally, rapidly or forcefully snapping the knees into hyperextension (especially repeatedly) while under load from the barbell will likely lead to unnecessary soreness or irritation within the joint or from the joint capsule itself. As a general rule, the heavier the load on the lifter, the more mindful they should be about hyperextending the knee.

So, now we’ve got our definitions in place, let’s recap:

“Locking out” the knee refers to straightening the knee until it can no longer straighten due to the anatomical limitation of the joint itself. For some lifters, this will be when the knee is relatively straight, while for others, it will be when the knee is hyperextending. If the knee locks out without any hyperextension, it’s likely not an issue for a healthy set of knees.

If, on the other hand, it locks out into hyperextension, it could lead to irritation in the knee as time goes on (there are numerous factors to consider with this, though, just so we’re clear).

“The world of strength training is all about individualization; our bodies all tolerate exercises, movements, and positions differently. Additionally, we all have different goals. So, whether you should lock your knees or keep them bent should take these factors into account. Do what’s best for you and your needs, and you’ll be just fine.”

What happens when the knees are truly locked out?

Locking out the knees to their full extent allows the weight of your upper body and any weight across your back to run directly through the knee joint itself. When this occurs, the weight above your knees is “stacked” directly on top—and now running through—your knees. This direct, downward force running through the shaft of the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia) and subsequently on the end of each bone (forming the knee joint) is known as axial compression.

When this direct, axial compression occurs, the muscles that cross your knee joint and help to contribute to your squat don’t have to work nearly as intensity to hold your knee joint in place (they’re still working, mind you, but much of the knee’s required stability will now come from the joint capsule and surrounding ligaments).

Related article: Here’s How To Recover Way Faster After Leg Day (Science-Backed)

As a result, your leg muscles (notably the quadriceps muscles) get to rest to a much greater extent than if being forced to hold the knee in a slightly bent position. The trade-off is that now more weight is running through (and acting on) the actual joint itself since the muscles crossing the knee are in a more relaxed state.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, so long as you have a healthy set of knees, but if you have cartilage issues or joint issues of any type within your knee(s), the greater amounts of compressive force now running directly through the joint itself might be painful or irritating (I will elaborate more on this later in the article).

What happens when the knees remain slightly bent?

Keeping the knees slightly bent (often known as a soft bend) at the top of the squat forces the muscles crossing over the knee joint, particularly the quadriceps muscles (via the common quadriceps tendon), to remain active and engaged at all times, if these muscles were to “shut off” the knee would keep bending forward, and you would collapse toward the ground.

But since the knee must remain in a bent position, the surrounding muscles have to continually “clamp down” by producing what’s known as an isometric contraction to ensure the knee joint doesn’t continue to bend forward.

Pro tip: the greater the angle of bend you keep in your knee at the top of your squat, the more aggressively your muscles will need to work to hold you in this position.

Again, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this, either. Rather, you must merely be aware of what it equates to in terms of additional energy expenditure between each rep and whether this is in line with, or a hindrance, to your training goals. Depending on your needs, this could be your best friend or your worst enemy.

Let’s look at these pros and cons in greater detail in the following sections!

“Any time you plan on placing a barbell across your back to bang out some squats, it’s a good idea to consider whether it’s in your best interests to keep your knees bent or keep them straight at the top of the rep.”

Benefits: locking the knees

Fully straightening your knees between each repetition of a squat can have plenty of benefits. As I discuss each of them below, keep in mind that this is all in reference to an otherwise healthy set of knees; if you have previous knee injuries (cartilage issues or instability issues, etc.), what follows below may not be beneficial for you. I’ll discuss these considerations later in the article.

Also, be aware that the following benefits are of equal extent as each one can be incredibly advantageous for the lifter.

Benefit 1: Allowing for mental preparation before the following rep

Well-executed, technically crisp squats come down to mental focus. Any time each repetition of your squats is mentally taxing, having a few extra seconds to dial in your focus can be immensely helpful—both for your technical execution of the movement and to psych yourself up (particularly if you’re using heavy loads).

Having a few extra seconds to mentally prepare for the upcoming rep is very helpful for those who:

- Are new to learning and mastering their squat technique.

- They are squatting relatively heavy loads across their back.

In either situation, there can be a lot to mentally process to ensure technical proficiency and a successful upcoming repetition. With either circumstance, keeping the knee bent between each squat can use up precious lower body energy that may lead to a sloppier, less technically proficient squat. It can even cause a lifter to miss the lift entirely.

There are times, of course, when using extra energy between each repetition by keeping the knees bent can be a good thing (discussed a bit later), but in this context, it’s not ideal.

Benefit 2: Allowing for minute positional adjustment and recalibration

Just with the previous section discussing the need for mental adjustment between each squat, there’s also a benefit to having time to physically adjust and re-establish perfect position (lateral balance, forward and backward balance, torso angle, etc.) between your repetitions.

The scenarios are the same; allowing for these minute (but necessary) positional adjustments pay the largest dividends for those who are still learning to master their squat technique and for those lifting relatively heavy loads.

Related article: When You Should And Shouldn’t Squat Barefoot (And Why It Matters)

While these types of adjustments can perhaps be made without fully extending the knees, lifters will likely find it easiest to make such recalibrations to their position with the knees in a straightened position. This is not to say that the knees must be locked out to do this, but rather that the straighter the knee is, the more natural or easy it will likely be to make any needed changes.

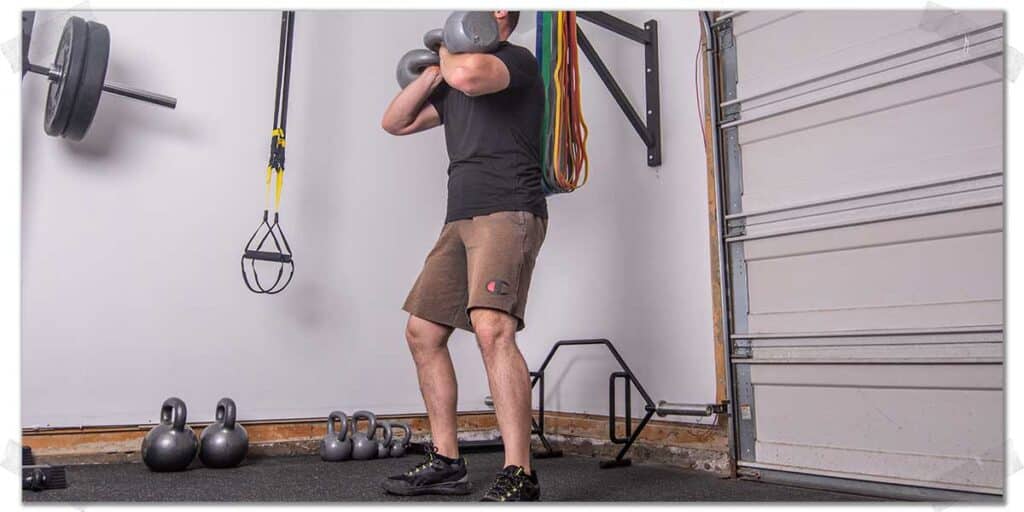

Benefit 3: Allowing for micro-recovery before commencing the next rep

Locking the knees at the top of each squat is very common (and arguably necessary) when performing multiple (two or more) repetitions with heavy loads. When your squats are heavy enough that near maximal effort goes into each rep, having a few extra seconds can be the make-or-break factor for the next repetition.

This is a scenario when conserving as much lower body (and even upper body) energy between each repetition is of paramount importance. And suffice it to say, you will be bleeding precious energy if your knees are even slightly bent as you rest at the top of your squat.

Resting an extra two or three seconds between repetitions may not sound like much time for recovery, but this micro-break can be surprisingly helpful for muscle recovery between repetitions.

Benefits: not locking the knees

Just as there can be benefits with locking out the knees when in between squat repetitions, there can also be benefits for keeping a soft bend rather than keeping them fully straightened. There are two main benefits in particular, one of which can be for the well-being of the knees while the other is for performance-based benefit.

Benefit 1: Less compressive force running through the joint itself

Any time you move your knee from a straight to a bent position (and then hold the bend), the mechanics of the knee change in a manner that forces your muscles to maintain a heightened state of contraction. Additionally, your center of gravity changes ever so slightly (the bigger the bend, the more it changes).

Without going into some gnarly biomechanics (which I’m not all that great at, anyways), what ultimately happens is the muscles (and their respective tendons) that cross over the knee joint engage in a way that can offload some of the direct force that would otherwise run in an axial direction (along the length of the bones) through your knee cartilage.

To be clear, you’ll still be experiencing joint compression; it’s not as if the joint is magically offloaded from the forces of gravity and any weight above the knee that’s acting upon it. Rather, the muscles can help absorb a portion of it in a way that the cartilage would otherwise have to directly absorb through axial compression.

From a joint health perspective, this can come in quite handy if you have knees with previous injury or instability (discussed later in this article).

Benefit 2: Continual time under tension (TUT) of the lower body

By maintaining a small bend in your knees when at the top of your squat, you’re forcing the muscles (and their respective tendons) that cross the joint to endure a continual state of mechanical tension at all times. This means that there’s no rest between repetitions for your already weary legs that are tiring out from your squats.

Ultimately, this leads to a greater length of time for which your leg muscles are exposed to continual tension, which in the world of strength training, is known as time under tension (TUT) training.

The benefit to be had here is potential gains in muscle size (hypertrophy) and strength, as TUT training can have its advantages for those who have their primary goals based on improving muscle size and those who want to improve their strength without lifting excessively heavy loads.

Pro tip: For best results, aim for a continual state of tension on your muscles lasting between 60 – 90 seconds, as this duration of continual muscle tension while under load has been shown to produce favourable gains in muscle characteristics relating to size and strength. In other words: make your squat set last upwards of 90 seconds while always having your leg muscles engaged!

When to: making the best decision for squatting

Any time you plan on placing a barbell across your back to bang out some squats, it’s a good idea to consider whether it’s in your best interests to keep your knees bent or keep them straight at the top of the rep.

When to consider locking your knees

The following points and scenarios below will help provide confidence in knowing that it’s likely acceptable and beneficial for you to lock or fully straighten your knees between each squat you perform.

- You have an otherwise healthy set of knees that can tolerate the compressive force generated within and on the joint with the weight resting across your back (arthritic knees or knees with cartilage damage, for example, may not tolerate this).

- You do not have excessive genu recurvatum of your knees; your knees lock out at the fully straightened position without any excessive backward bending. If you have knees that hyperextend, don’t lock them out; extend them until they’re straight without further extending beyond this point.

- You need extra time before your next squat, be it for physical positioning adjustment or mental preparation. This is most often required for novice squatters and those lifting relatively heavy or near-maximal loads.

When to consider not locking

Locking or fully straightening your knees between squats might be something worth avoiding if you meet any of the following brief points listed below:

- You have a pre-existing knee injury that compromises the stability of the joint. Injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tears might lead to instability of the knee when it’s fully locked out, which is something you absolutely want to avoid when you have a load placed across your back.

- You are using relatively light loads (less than 40 percent of your one-repetition maximum (1-RM). With lighter loads such as these, you likely don’t need the micro-recovery or mental preparation required for each subsequent rep that you otherwise would for heavier loads.

- Your training goals involve enhancing lower body endurance and muscular hypertrophy of your legs. Keeping your knees bent throughout the entirety of your squat set will force your legs to undergo a much greater extent of continuous muscular tension, which produces greater enhancement of muscular endurance (the muscles’ ability to resist becoming tired) and muscular hypertrophy (muscle size).

Final thoughts

To lock or not to lock isn’t as straightforward of a debate as many physically active individuals and lifters make it out to be. The world of strength training is all about individualization; our bodies all tolerate exercises, movements, and positions differently. Additionally, we all have different goals. So, whether you should lock your knees or keep them bent should take these factors into account. Do what’s best for you and your needs, and you’ll be just fine.

Frequently Asked Questions

I like being as helpful as possible in the articles I write. As such, I’ve included a few brief answers to some commonly asked questions pertaining to squats, knee positioning, and what’s likely best for lifters.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!