If you’re dealing with hamstring pain from deadlifts, we’ve got some stuff to talk about; sometimes it’s normal, and other times it’s not. The bottom line is that deadlifts are an absolute staple when it comes to building a stronger, more capable body, so you want to do them for all your days ahead. Pain has no place at the table, so it needs to be eliminated. And that’s what we’ll cover in this article.

The hamstring muscles play a prominent role in deadlifts. Delayed muscle soreness and discomfort can be entirely normal. Pain—during or after—deadlifts is not normal. There can be numerous reasons for hamstring pain, and thankfully there are often effective solutions for each.

So, let’s take it from the top; I’ll go over the basic biomechanics and anatomy involved with deadlifts, how to interpret, prevent and modify your pain, and even give you some deadlift variations you can try if you need to let up a bit on your hamstrings.

So, let’s get to it.

Related article: Straps vs. Mixed Grip When Deadlifting (Pros & Cons of Each)

Basic hamstring anatomy & function

The hamstrings are comprised of three individual muscles. These muscles are:

- The semitendinosus

- The semimembranosus

- The biceps femoris (which has a long head and a short head)

These muscles have two primary roles within the lower body:

- Producing knee flexion (bending the knee)

- Producing hip extension (pulling the leg directly behind you)

The hamstrings are unique in this regard since they can produce two distinct movements of the leg. They can do this because they cross the hip joint (which allows them to pull the leg backwards) and the knee joint (allowing them to bend the knee). Hence, the hamstrings are known as a two-joint muscle.

Two-joint muscles have unique properties when compared to one-joint muscles. In particular, these muscles are capable of two rather distinct features: active insufficiency and passive insufficiency.

Active insufficiency

Active insufficiency is the result of a two-joint muscle shortening the distance between each joint that it crosses. Essentially, the shorter the muscle becomes as it contracts at one joint, the less contractile force it can produce at the other. This typically isn’t much of an issue regarding hamstring pain from deadlifts, but passive insufficiency (below) is a different story.

Passive insufficiency

Passive insufficiency is the result of a two-joint muscle being lengthened by both joints. In this context, the more the muscle is lengthened at one end of the joint, the less able it will be to lengthen out at the other joint. This can be a significant contributing factor to hamstring pain when deadlifting if performing the Romanian deadlift (discussed later in this article).

When it comes to deadlifts, the more passive insufficiency you have, the greater the risk of the hamstrings becoming overstretched, leading to muscle strain.

This will come back to play later in the article when I discuss deadlifting modifications and variations you can try.

Interpreting your pain

While pain is rather subjective, how it behaves can offer some telltale signs of which tissue(s) or structures are affected and causing your pain. Sometimes hamstring pain can result from lousy mobility, but other times it’s not so simple.

Before you start blasting your hamstrings with stretches or other movements, you must ensure you know what you’re up against. Different treatment techniques are required for different types of injury or dysfunction; at best, using the wrong treatment technique won’t net you any gains. At worst, it can increase your pain and worsen the issue altogether.

What’s discussed below are some of the more prominent pain generators when dealing with hamstring pain. (I can’t cover everything within a single blog article.) As always, I advocate for a professional evaluation if your pain is more than minimal or if it’s ongoing.

Hamstrings vs. Sciatic nerve tension

I’ve written about this extensively in my other blog posts Hip Hing Hamstring Pain: Causes & Solutions and One Hamstring Tighter than the Other? Here’s Your Solution, so be sure to check those articles out for some key details that I won’t be re-hashing here.

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in your body, running down the back of your leg along with the hamstrings. This nerve is prone to becoming sensitive to stretch or rigorous movements for various reasons.

Mild sciatic nerve tension is often confused with hamstring pain. It’s absolutely critical to know whether you’re dealing with a hamstring (muscular) issue or a sciatic nerve (neural) issue since they require entirely different treatment interventions. Additionally, treating sciatic nerve tension like a hamstring issue will likely worsen the issue.

Nerves are like any other tissue in our body; they can become irritable and sensitive. When this occurs, regular movements can produce discomfort, or the nerve can be extra alert to movements that are taking place. The specifics of this are way beyond the scope of this article, but essentially we’re talking about a phenomenon known as the mechanosensitization of nerves.

When this phenomenon occurs, a nerve will not like to be held in a prolonged stretching position. Doing so can further irritate the nerve, so it must be addressed through other means of movement.

If it’s purely sciatic nerve tension you’re dealing with, the solution is to instead opt for nerve glides (also known as nerve flossing), which will work to decrease the nerve’s sensitivity to being stretched.

Keep in mind: It’s entirely possible to have sensitive or irritated neural tissue and an additional issue (such as a tight muscle) or lousy hip joint mobility. There’s no rule saying you can only have one thing causing or contributing to your pain.

If you want to learn how to differentiate pain between the hamstrings and the sciatic nerve, check out my article: Hip Hing Hamstring Pain: Causes & Solutions

Generalized muscle tightness

If you know that your hamstring pain is the result of outright poor mobility, this can be relatively straightforward to treat (you’ll learn how to do this in the posterior chain section of the article.)

Out of all the different reasons for experiencing hamstring pain, generalized muscle tension is likely a best-case scenario here; it’s often quick to clean up and a relatively straightforward process. It’s often much quicker to resolve than tendinopathy (which is rather common and discussed below). Just make sure you know that your stiffness isn’t the result of sciatic nerve irritation.

A great starting point is to incorporate an effective dynamic warmup routine (link takes you to four of my favorite routines) into your training sessions, which will appropriately prepare your muscles, tendons, hip joint, and nervous system for keeping your hamstrings strong and your deadlifts heavy.

Dull, achy, intermittent pain (the dreaded tendinopathy)

If you find that the pain in your hamstrings feels more like a dull, aching pain, you may be feeling the effects of an unhealthy hamstring tendon (not the muscle itself). This is especially true if you feel this type of pain high up the back of your leg, right underneath your sit bone (just underneath the crease of your butt cheek, which is called the gluteal fold).

The generalized umbrella term for an unhealthy tendon is called tendinopathy. There are different sub-classifications of tendinopathy (tendinitis, tendinosis, tenosynovitis), but for the sake of this article, I’m just going to use the umbrella term. In the case of the hamstrings, tendinopathy of the upper hamstring tendon is most common in younger and physically active individuals. It doesn’t seem to occur much in the distal hamstring tendons (the tendons that cross the knee and attach to your tibia).

Pro tip: an upper hamstring injury is often called a proximal hamstring injury.

If you happen to find that your hamstring pain is often worse or more notable after having been still for a while (such as at night, when waking up in the morning, or after laying on the couch for a while), it could be another sign of pain arising from the tendon, indicating the presence of tendinopathy (unhealthy tendons often become notably uncomfortable after receiving little movement).

Individuals with proximal hamstring tendinopathy also report pain worsening when running at fast speeds or after prolonged sitting.

So, if any of those symptoms are relatable, you might just have tendinosis (but get it confirmed through a qualified clinical evaluation).

The solution for tendinopathy

This could be a bit of an uphill battle, but it’s one that is often entirely doable. Likely, it will primarily come down to how extensive the tendinopathy is and how committed you are to overcoming the issue.

The best starting point here is to read the following article from the National Library of Medicine:

Proximal Hamstring Injuries: Management of Tendinopathy and Avulsion Injuries

It will walk you through the scientific evidence and general consensus for how to best start getting the issue under control.

Pro tip: If you enlist the help of a qualified healthcare practitioner (such as a physical therapist), see if they have access to shockwave therapy, as it has been shown to be quite helpful in treating upper hamstring tendinopathy.

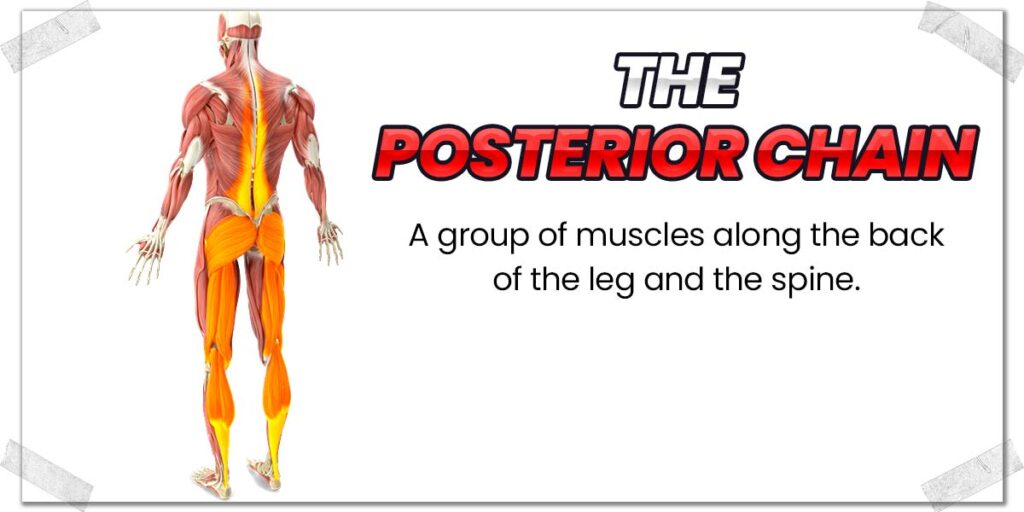

The global picture: Dysfunction in the posterior chain

The posterior chain refers to a collection of muscles on the backside of the body that collectively work to produce various full-body movements involving extension of the body. Movements such as sprinting, jumping, and…wait for it…deadlifting are examples of movements that require the posterior chain to work aggressively to make these movements happen.

The hamstrings are one of the critical muscle groups that comprise the posterior chain, and you can’t perform a deadlift (of any kind) without bringing your hamstrings to the party.

Why is this important to know? Ultimately, when one area of the posterior chain is weak or has inadequate mobility, it can force other muscles within the chain (in this case, the hamstrings) to endure excessive strain as a means to compensate. Let’s look at the implications of this a bit closer.

Strength deficiencies in the posterior chain

The powerhouse muscles responsible for the deadlift are predominantly the gluteal muscles (the gluteus maximus, in particular), the hamstrings, and the erector spinae. Nearly every muscle on the backside of your body is working in some capacity throughout the movement, but we’re simply focusing on the primary muscle groups here.

Related content:

For many lifters, the phenomenon of gluteal amnesia rears its ugly head into the deadlift, whereby the gluteal muscles aren’t exhibiting an ideal neurological output during the movement (meaning they aren’t contracting and thereby producing as much muscular force as they should).

When this happens, the hamstrings and lower back are now left with a larger role to play when completing the deadlift, essentially shifting them into “overdrive,” which can lead to excessive muscular strain.

Ironing out deficiencies

If you feel like your hamstrings are taking the brunt of the effort with your deadlifts, it’s worth ensuring that your glutes haven’t “fallen asleep” on you. The easiest way to ensure they’re operating at full throttle throughout a posterior chain-dominant exercise is to incorporate some direct glute exercises into your training.

Doing so will force these muscles to “wake up” since the glutes must contribute most of the muscular effort needed to complete the exercise.

Pro tip: Performing a moderately challenging glute-dominant exercise for a set or two (typically for a few reps per set) can help prime your glutes for better activation during the deadlift through a phenomenon known as neural potentiation.

Some common (and effective) gluteal exercises to try include:

- Barbell hip thrusts

- Bent knee Supermans

- Glute bridge marches across a bench

Mobility deficiencies in the posterior chain

The other common issue within the posterior chain is poor mobility. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and when one area of the body doesn’t move as ideally as it should, the chain undergoes abnormal stress and strain, leading to pain and even injury (the metaphorical “breaking” of the chain).

Sooner or later, when these mobility issues are present, pain is bound to show up (in the hamstrings or elsewhere). Take your mobility seriously – prevention is better than any cure.

Moving well throughout the posterior chain

Keeping your posterior chain “greased” and moving well is a whole other article in itself. Nonetheless, ensuring that you can attain and hold ideal deadlift positioning throughout all phases of the deadlift (most notably when in the wedge position at the bottom of the deadlift) is the foundation for avoiding hamstring pain when deadlifting.

If you struggle with mobility at the bottom phase of the deadlift, you’ll need to incorporate strategies such as switching to rack pulls (discussed in depth later on within this article) until you get the chain greased enough to move flawlessly at the bottom of the deadlift within the wedge position.

Performing the deadlift while unable to hold perfect technique can lead to significant hamstring issues or lower back issues. Whether your technique is from a lack of experience or poor mobility, modifying your deadlift should be priority number one until the issue is resolved.

If you find your body feels lousy when in the wedge position (bottom position of the deadlift), take the time and effort to work on the body parts that feel lousy by performing some dedicated mobility work and soft-tissue treatments (various methods of foam rolling, IASTM, massage, etc.). Take a handful (or more) of weeks to commit yourself to this dedicated mobility routine, and it should produce noticeable results thereafter.

Hamstring rehabilitation strategies

The best way to rehab a hamstring injury or eliminate pain is through seeking treatment from a licensed healthcare professional and taking an active role in your recovery as they guide you along in the process.

However, this may not be feasible for you, so below are some common self-treatment strategies often employed by athletes working through hamstring issues on their own. Please remember that anything you try is not without risk. While the following strategies are usually quite safe (when performed properly), there are times when a particular treatment may not be appropriate for you. Speak with a medical professional if you have any uncertainty.

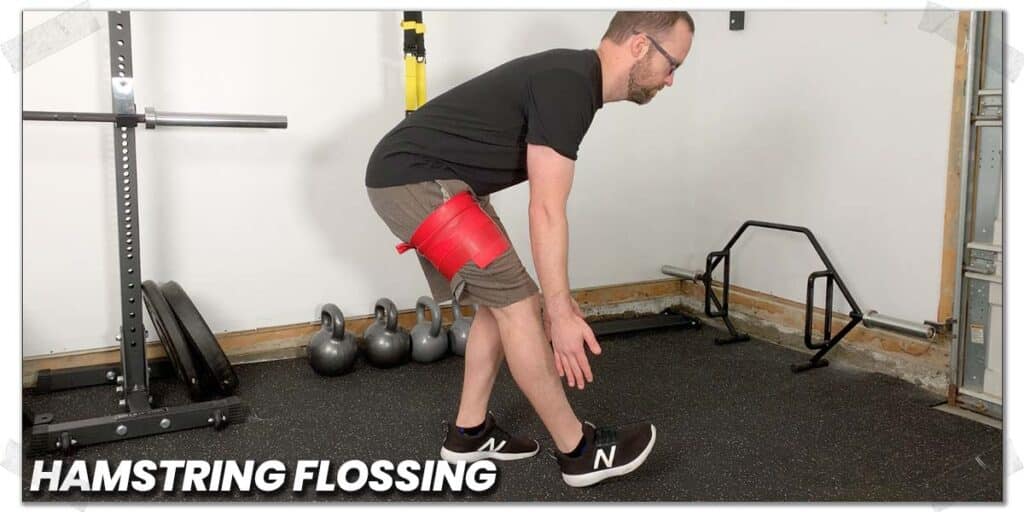

Compression flossing

Compression flossing (often referred to as voodoo flossing or tack-and-floss) is a newer self-intervention technique with some surprising evidence to back it up.

The technique involves wrapping a latex band around one of the extremities (in this case, the thigh) with mild to moderate amounts of compression. Typically, the band is wrapped over the portion of a muscle (or group of muscles) that is tight and myofascially restricted (resulting in poor mobility).

Once the band is in place, the individual performs a series of movements for upwards of approximately two minutes with the wrapped extremity. These movements force the muscles that are “pinned down” underneath the band to endure shearing forces that help restore mobility to the muscle.

In the case of the hamstrings, compression flossing movements that may be effective include:

- Squats and lunges

- Hip hinges (for upper hamstrings)

- Supine straight leg raises (for upper hamstrings)

- Supine bent-knee extensions (for mid and distal hamstrings)

Ultimately, the right movement or series of movements comes down to what feels best for the individual. Compression flossing shouldn’t be painful, so if you give it a try, make sure the movements don’t produce any pain.

Pro tip: when compression flossing is performed, the band is usually pulled to no greater than 50% of its maximal stretch.

This technique works best for:

- Muscles that are chronically stiff and sore.

- Muscles that have reduced mobility compared to the same muscles in the opposite extremity (even if not painful).

- Joints that are stiff and have reduced mobility.

Sciatic nerve glides

Nerve glides are a type of neuromobilization technique that work to restore a nerve’s neurodynamic abilities. If that sounds complicated, don’t worry; it simply means that it’s a type of movement that reduces the heightened mechanosensitivity (sensitivity to movement) that nerves can experience when irritated or in a state of chronic tension.

There are different ways to perform neuromobilizations for the sciatic nerve. Check out the video below from the Physio Tutors on some more common variations to try.

And always remember: with neuromobilizations, you only want to produce a mild (and short-lived stretch). You NEVER want to perform aggressive neuromobilizations or hold the stretch for more than one second at a time, as this will often only serve to irritate the nerve even further.

For best results, I often recommend to my patients to start by performing these exercises once per day, typically for around twenty repetitions. If the first session is tolerated well, I have them perform the exercise twice the following day. If that session is tolerated well, I’ll have them perform them three times the next day.

I have them slowly scale up to ensure the nerve does not become irritated from the mobilizations. Upwards of five times per day can yield significant reductions in sciatic nerve tension if performed correctly.

Deadlift variations

For most lifters, experiencing mild hamstring pain doesn’t necessarily mean they have to instantaneously ditch the deadlift. Of course, they may need to forego it for the time being, but usually, it’s worth experimenting with variations of the deadlift to see if the pain in question can be avoided altogether. If so, you may just have a winning ticket that allows you to keep deadlifting while you work to resolve the underlying cause of your hamstring issue.

Below is a common deadlift variation to avoid and some common variations to try when working through your hamstring issue.

Avoiding Romanian deadlifts (for the time being)

Whether it’s the double-leg or single-leg Romanian deadlift (RDL), this deadlift variation may be worth avoiding for the time being since it demands greater physical lengthening when lowering the weight and greater contraction of the hamstrings when raising the weight.

There can certainly be a lot to unpack here; the Romanian deadlift can actually be a terrific later-stage rehab exercise for unhealthy or injured hamstrings (especially if it’s the upper hamstring). However, I know nothing of you and your hamstring pain. So, the best I can do here is to raise your awareness of the fact that the RDL places an overall greater demand on the hamstrings throughout the movement.

Rack pulls

Not everyone can—or should—deadlift straight off the floor. Plenty of people don’t have the mobility to maintain pristine form as they pull the weight upwards. In contrast, others experience pain in their hips or low back as they get into the starting position or begin to pull the weight off the floor.

The solution here is to shorten the range of motion required when deadlifting. And this is where rack pulls can do wonders.

What are rack pulls?

Rack pulls are a deadlift performed through a shortened range of motion. They’re often utilized for pulling heavier amounts of weight than what can be pulled from the floor. But that’s not what we’ll use them for in this circumstance.

Instead, we’ll see if you can use them to continue to deadlift (either with the same load you pull off the floor or lighter) without experiencing hamstring pain.

Depending on your specific cause, type, and extent of hamstring pain, this may be possible since the hamstrings will have to work through a shorter range of motion, which will be less demanding on them. Hopefully, this will allow you to stimulate them in productive ways without drumming up pain in the process.

How to perform rack pulls

In the case of hamstring discomfort or pain, performing rack pulls starts with finding a range of motion that you can work within without experiencing pain. So, you’ll need to experiment to determine what an ideal rack height is for you.

Start by setting the rack/pins high enough so that you only perform the last quarter range of the deadlift.

If that is tolerated well, try lowering the pins at a height that allows you to pull through half of your normal range of motion.

If no pain is experienced, try lowering the pins around the 3/4 range of motion and pulling from there.

It’s probably not worth going much lower than this, but you can certainly play around with it. Keep fine-tuning your height until you are using an ideal range for your abilities.

Remember: You’re not resigned to performing rack pulls for the rest of your days ahead; working this modified range of motion can be an effective workaround so that you can continue to deadlift and pull some weight while you work to clean up and resolve your hamstring issue.

Ideally, you’ll want to set the rack at the lowest height possible without experiencing pain. This will allow you to lift through the most extensive range of motion possible while avoiding irritation or discomfort in your hamstring.

For typical hamstring injuries such as hamstring strains, proximal hamstring tendinopathy, and general muscular stiffness, the larger the range of motion, the more pain provocation there will be. This usually becomes more notable as the barbell gets closer to the floor since the proximal hamstring is lengthening out in this position.

Tempo-based deadlifts

If you’re still looking to pull weight directly off the floor, this may be doable as well. But if you can only do so when deadlifting ridiculously light weights, you won’t be getting adequate stimulation to your muscles. And unless you’re deadlifting merely to practice your form, what’s the point of deadlifting if your muscles won’t get adequate stimulus?

Depending on the extent and irritability of your hamstring pain, you may have success with tempo-based deadlifts. This style of deadlift involves lifting a lighter load but while doing so at a notably slow speed for both the concentric (upward) and eccentric (downward) phases of barbell movement.

It’s a training technique known as time under tension (TUT), and it can lead to significant improvements in muscle size and strength when appropriately performed.1–3

The beauty here is that you can potentially get the best of both worlds: deadlifting without causing hamstring pain while also improving your hamstring strength. Of course, it will depend on the type and extent of your hamstring pain or injury. Still, if your pain is on the mild side and only shows up when you’re deadlifting rather heavy loads, TUT might be an ideal workaround for the time being.

Pro tip: if desired, you can combine TUT deadlifts with rack pulls.

Final thoughts

Hamstring injuries in athletic populations are quite common, so don’t freak out if you’re having hamstring pain with movements and exercises such as deadlifts. Muscular fatigue in the hamstrings during a deadlifting session is perfectly acceptable, and discomfort or soreness after a deadlifting session is a common and normal occurrence.

Pain in the hamstrings—during or after a deadlift session—isn’t normal. Depending on the nature and intensity of the pain, it may not mean you have to forego deadlifts for the time being if you can find and employ some appropriate strategies for the time being.

Get a professional evaluation, if possible, and work to train around the issue rather than push through it as you strive to get your hamstring(s) back to full health.

References:

1. Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojda\la G, Go\laś A. Maximizing muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review of advanced resistance training techniques and methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):4897.

2. Pereira PEA, Motoyama YL, Esteves GJ, et al. Resistance training with slow speed of movement is better for hypertrophy and muscle strength gains than fast speed of movement. Int J Appl Exerc Physiol. 2016;5(2).

3. Tran QT, Docherty D, Behm D. The effects of varying time under tension and volume load on acute neuromuscular responses. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98(4):402-410.

Hi! I’m Jim Wittstrom, PT, DPT, CSCS, Pn1.

I am a physical therapist who is passionate about all things pertaining to strength & conditioning, human movement, injury prevention and rehabilitation. I created StrengthResurgence.com in order to help others become stronger and healthier. I also love helping aspiring students and therapists fulfill their dreams of becoming successful in school and within their clinical PT practice. Thanks for checking out my site!